Communicating with Clarity: Helping Children Understand the What, Why, and How of Their Learning

You are here

Early childhood is a pivotal time in a child’s lifelong learning path. As early childhood educators, we have the opportunity to create meaningful experiences that can positively impact learners’ development across content areas and developmental domains. The ways we intentionally communicate with learners can determine the effectiveness of their learning experiences: Do we use language intentionally? How do we communicate to children what they are learning, why they are learning it, and how they will know when they have learned it? This is communicating with clarity.

Communicating with clarity is essential in all early childhood settings and across all developmental domains. It requires educators to use a variety of instructional modes and intentional, language-based interactions with children (Thunder et al. 2022). Such intentionality fits into the framework of developmentally appropriate practice (DAP) by creating opportunities for educators to respond to each and every child’s individuality and contexts (NAEYC 2020). It also creates opportunities for educators to better communicate and partner with families in respectful and reciprocal relationships (Thunder et al. 2022).

We (the authors) are educators who are passionate about developing the expertise of teachers by translating research into practice. We each bring unique perspectives to early childhood from our current and previous roles as early childhood teachers, special educators, instructional coaches, methods professors, and directors of child development and preschool programs. We have written extensively about communicating with clarity and intentionally empowering children to drive their learning. In this article, we define clarity and the role it plays in learning, then we outline four essential strategies that early childhood educators can follow to communicate with clarity in their settings. We show these essentials in action across a variety of early learning activities. We conclude with questions educators can ask as they reflect on their current practices and take action to communicate with clarity in their learning settings.

What Is Clarity for Learning?

Clarity for learning is an essential component in early childhood education (Titsworth et al. 2015; Thunder et al. 2023). It refers to educators’ and learners’ awareness of the what, why, and how of learning (Corwin Visible Learning Plus, n.d.). For teaching to positively impact each child’s development and learning, educators, learners, and families must have a clear understanding of the intentions—or goals—of a learning experience and the criteria for attaining those goals. Communicating these intentions with clarity requires more than just providing directions at a learning center or at the beginning of an instructional activity. Rather, it asks educators to create a sense of purpose so that children see the relevance, meaningfulness, and authenticity of each experience and have agency in their learning (Thunder, Almarode, & Hattie 2021).

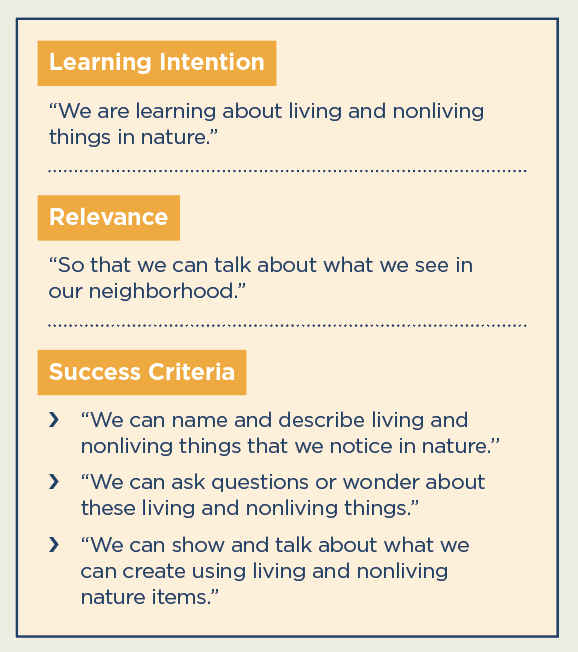

Early childhood educators begin the work of communicating with clarity by considering three guiding questions from children’s perspectives:

- “What am I learning today?” (learning intention)

- “Why am I learning this?” (relevance)

- “How will I know when I have learned it?” (success criteria)

When children can answer these questions, their learning is purposeful and impactful (Thunder, Almarode, & Hattie 2021). These questions are not stale statements; rather, they are the heart of dialogue, questioning, collaboration, personalized learning, and the development of self-regulation (Almarode et al. 2021). They serve as a compass for young learners to engage in the individual lines of inquiry that spontaneously arise during all learning experiences, including play.

Knowing the learning intention, relevance, and success criteria of an activity empowers young children to see the necessary ingredients of mastery and then be able to identify what they already know and can do and what they are ready to try next (Almarode et al. 2021). While the specific words used may differ from teacher to teacher and learner to learner, the meaning of these questions and their answers should be accessibly shared, received, and acted on by all.

Using the Term Success Criteria

We have intentionally labeled the third guiding question as success criteria. This term supports a strengths-based stance for both learners and educators by making explicit the pathway of learning and valuing where each learner begins along that path. Success criteria create an inclusive and equitable pathway of learning by expecting and offering multiple means of representing, expressing, and engaging in learning (Almarode et al. 2021).

Considering Children’s Individuality and Contexts

Communicating with clarity begins during a teacher’s planning process. As early childhood educators outline learning goals and plan specific activities, they must consider each child’s individual strengths, needs, and social contexts along with the general expectations and progressions of learning based on an understanding of child development (NAEYC 2020). When fashioning specific learning intentions, their relevance, and what it will look and sound like to demonstrate mastery of the learning (success criteria), educators must consider many factors. These include developmental variability; children’s prior opportunities, access, and familiar contexts; and cultural, linguistic, and ability diversity (Thunder et al. 2022), which resonate with the three core considerations within the DAP framework (NAEYC 2020).

Focusing on the what, why, and how of learning supports both learners and educators to notice and value children’s funds of knowledge (Vélez-Ibáñez & Greenberg 1992) and to intentionally move each and every child’s learning and development forward. By pairing intentional language with exploration, inquiry, modeling, and an array of other teaching strategies, educators encourage children to make connections, actively engage, self-monitor, and grow within their learning environments. Communicating with clarity scaffolds young children’s access to and ownership of their learning journeys (Thunder et al. 2022; Frey, Fisher, & Almarode 2023).

Communicating with Clarity: Essentials and Examples

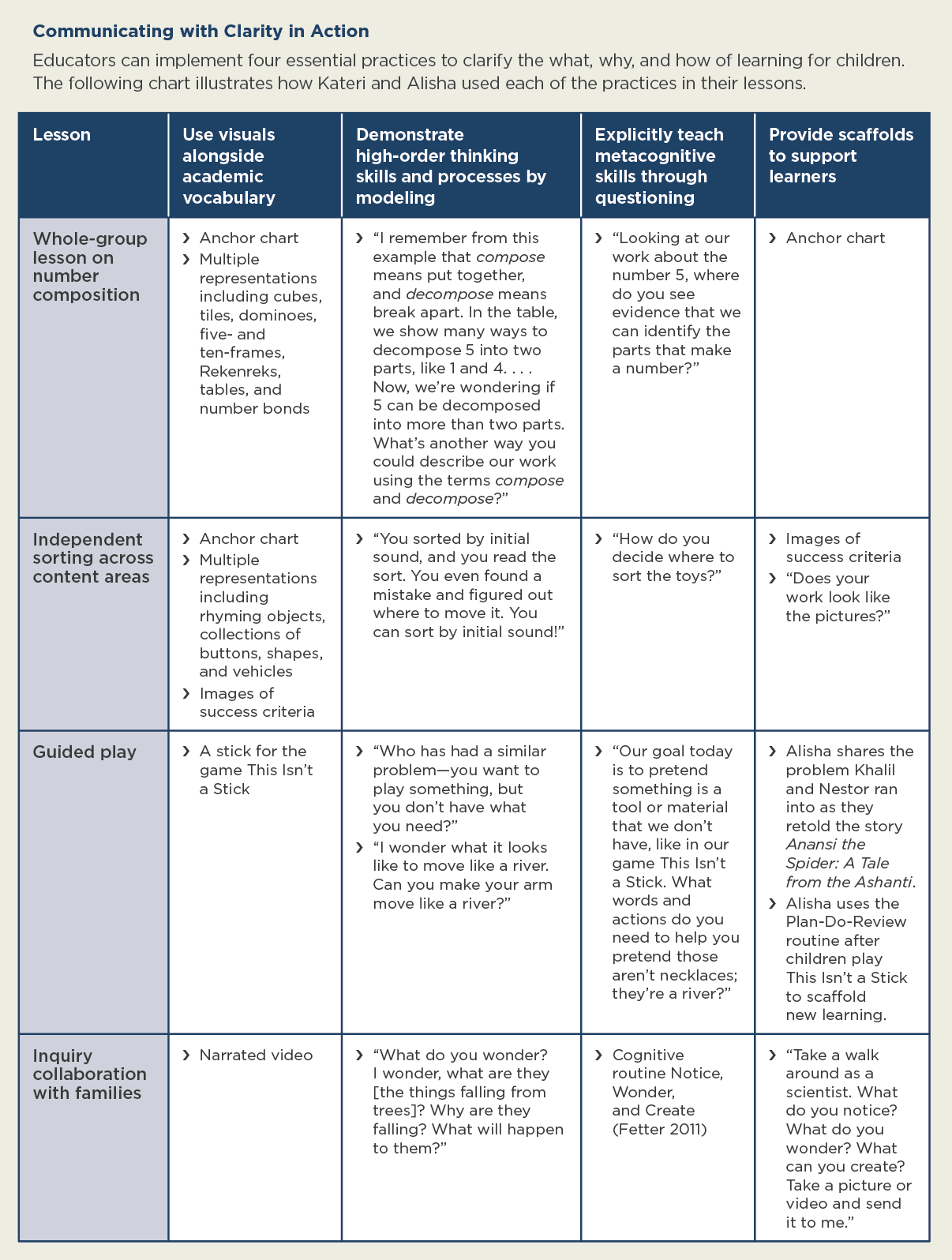

Educators can implement four essential strategies to ensure each and every child has the opportunity and access to understand and express their learning:

- Use visuals alongside academic vocabulary to help learners articulate what they are learning and connect multiple representations with academic vocabulary.

- Demonstrate high-order thinking skills and processes by modeling (thinking aloud) the connections between what children are learning and why.

- Explicitly teach metacognitive skills through questioning so that learners are guided to think about their own learning.

- Provide scaffolds (models, visual checklists, exemplars) to support learners as they begin to monitor their learning progress and to know what it looks and sounds like to meet the success criteria.

These essential strategies strive to make the what, why, and how of learning visible by modeling and scaffolding learners with multiple means of engaging, representing, and expressing their learning (CAST 2018). Through language, actions, objects, visuals, and interactions, the essentials also aim to leverage each child’s rich funds of knowledge and to communicate that they are capable of deep thinking and learning. These language-based, multimodal, and integrated attributes of communicating with clarity are essential to create equity in diverse, inclusive settings (NAEYC 2019).

Following, we present three learning activities that illustrate educators communicating with clarity. These come from the classrooms of Kateri and Alisha (the first and fifth authors, respectively). Kateri and Alisha teach in the same Title 1 public elementary school that serves about 300 students from prekindergarten (4-year-olds) through fourth grade. Kateri teaches an inclusive prekindergarten class of 18 children who meet specific criteria outlined by the school division and state to mean they are “at risk” of not entering kindergarten ready and are unserved by the federal Head Start program. Alisha teaches an inclusive kindergarten class of 24 children in a state where kindergarten is compulsory and in a community where nearly 40 languages are spoken. Each example opens with ways a child might answer the guiding questions related to learning intentions, relevance, and success criteria. Each essential strategy is noted in bold. (See “Communicating with Clarity in Action” at the end of this article for more information.)

Whole-Group Lesson on Number Composition

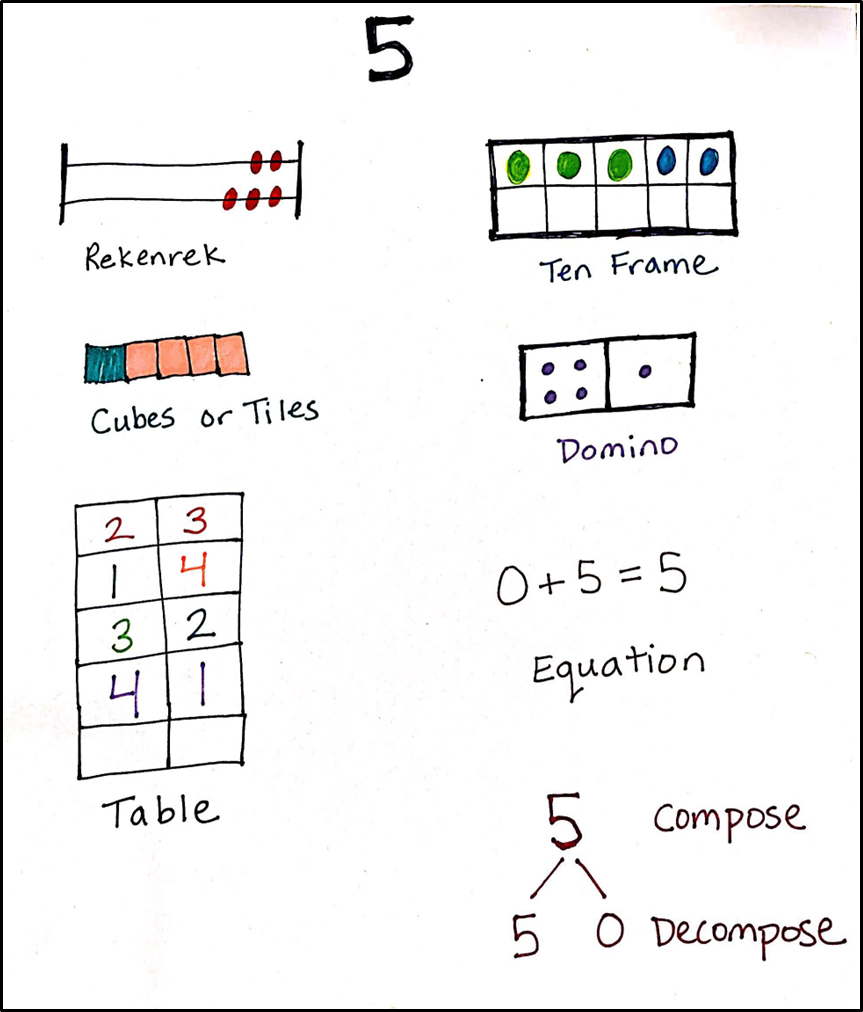

Alisha’s kindergartners are in the middle of an addition and subtraction unit. Yesterday, they explored number combinations to 5 using multiple representations, and they created an anchor chart of their work. Today, they will extend their work to number combinations up to 10.

Alisha’s kindergartners are in the middle of an addition and subtraction unit. Yesterday, they explored number combinations to 5 using multiple representations, and they created an anchor chart of their work. Today, they will extend their work to number combinations up to 10.

At the beginning of the lesson, Alisha introduces the children to what they will be learning, why they are learning it, and how they will know when they have learned it. Yet rather than reading these objectives aloud or using the phrases learning intention, relevance, and success criteria, Alisha asks the children to analyze the anchor chart (pictured to the right) to make sense of the experience to come and what they can expect to learn. (Use visuals; provide scaffolds.)

“Looking at our work about the number 5,” she says, “where do you see evidence that we can identify the parts that make a number?” (Teach metacognitive skills.) The children share the ways 5 is broken into two parts on each model on the anchor chart. Their discussion deepens as Jayden wonders, “Can a number be more than two parts?” Children respond with examples (“5 is made of 2 and 1 and 2.”) and nonexamples (“1 can only break into 1 and 0.”). The children know they can pose and answer mathematically rigorous questions.

Looking at the anchor chart, Alisha says, “I remember from this example that compose means put together, and decompose means break apart. In the table, we show many ways to decompose 5 into two parts, like 1 and 4. On the ten-frame, we show decomposing 5 into 3 and 2 and also composing by putting the dots together to make one row of 5. Now we’re wondering if 5 can be decomposed into more than two parts. What’s another way you could describe our work using the terms compose and decompose?” (Demonstrate high-order thinking skills.) Learners share their thinking and practice using this academic vocabulary.

Finally, Alisha asks, “Were we able to represent parts of 5 in different ways? What evidence do you see?” The children turn and talk with a partner to explain their thinking (teach metacognitive skills), pointing to the anchor chart frequently and sharing ideas about other manipulatives that could represent part-whole relationships, such as Cuisenaire rods, animal counters, and dice.

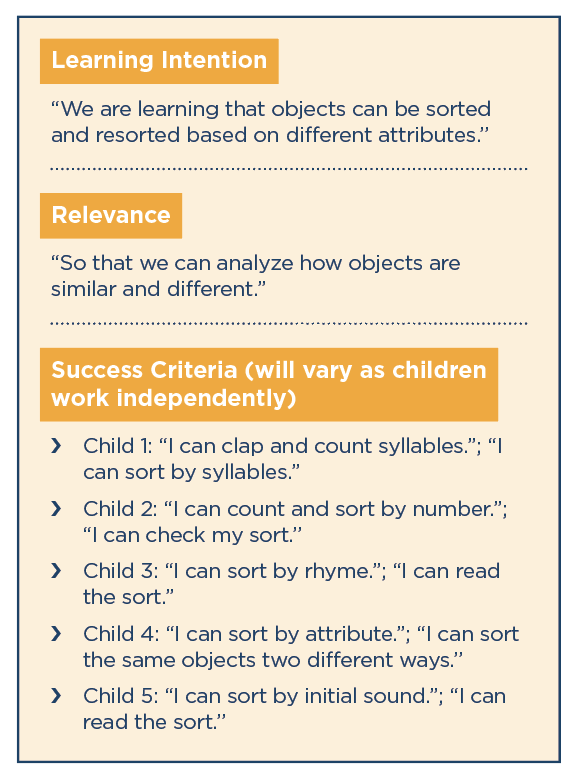

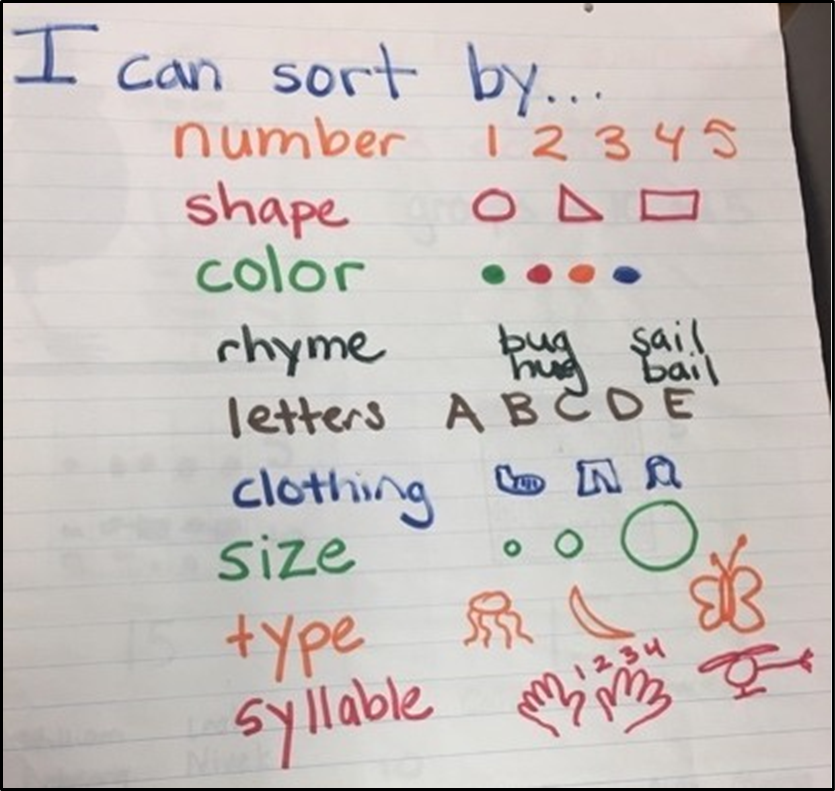

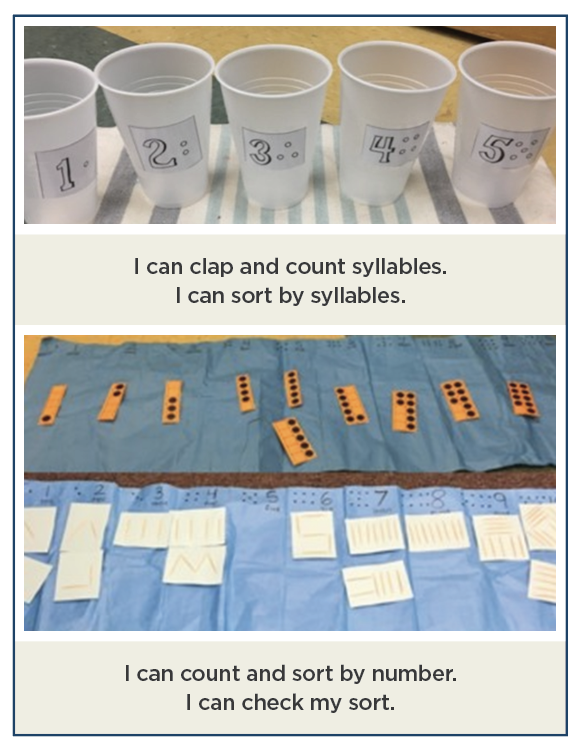

Independent Sorting Across Content Areas

Kateri’s prekindergarten class has been sorting to explore the planned learning intention. Together, they have created a list of attributes (see photo below).

Now, learners are spread across the room, working independently on a variety of cross-curricular tasks that involve sorting. Children are sorting number sets, rhyming objects, and collections of buttons, shapes, and vehicles. Each of their activity tubs has a laminated image of the success criteria. (Use visuals; provide scaffolds.) (See the photo below for an example.)

Kateri moves from learner to learner to confer and actively connect their independent practice to the learning intention and success criteria. She stops next to Reine and asks, “What are you learning?” (Teach metacognitive skills.)

Reine replies, “I’m sorting.”

“What are you sorting?” Kateri asks.

“These little toys.” Reine points to a filled tub with objects poking out. On the outside, there is a laminated image (shown below) similar to Reine’s work. (Use visuals; provide scaffolds.)

Kateri points to the image and says, “I see your work is set up like this picture. You’re putting the toys onto the chart. How do you decide where to sort the toys?” (Teach metacognitive skills.)

Reine explains, “When they start the same, they go together.” She digs into the tub and pulls out a small plastic web. “Web,” she says, then looks at her chart. “Web, jug. Web, kite. Web, light. Web, window! It goes here!” Reine puts the web under the image of a window, leans back, and announces, “I’m done!”

Kateri digs deeper. “You listened for the word with the same initial sound as window. Web, window. What sound do they both start with?” (Demonstrate

high-order thinking skills.)

“/w/” Reine replies.

“I see you’ve sorted everything in the tub. Let’s use the image to check if you’ve learned to sort by initial sound,” Kateri says. She then references the success criteria photo. “Does your work look like this picture?” (Use images; provide scaffolds.)

Reine looks at the image and her chart. “Yes.”

“You just explained and showed how you decided where to sort the toys by their first sound. You can sort by initial sound. Next, can you read your sort?” Kateri asks.

Reine reads the headers and names the objects underneath. “Jug, jet, jellyfish, koala.” She pauses and picks up the koala.

Kateri asks, “What are you thinking?” (Teach metacognitive skills.)

Reine looks at the koala and says, “That doesn’t sound the same. Koala. /k/. That should go with kite.” She moves the koala and returns to reading the sort. When she finishes, she looks up with a big smile.

“You did it!” Kateri says. “You sorted by initial sound, and you read the sort. You even found a mistake and figured out where to move it. You learned to sort by initial sound!” (Demonstrate high-order thinking skills.)

Guided Play

At the beginning of indoor play centers, Alisha and her class sit together. She shares a problem one group ran into yesterday: Khalil and Nestor were retelling the story of Anansi the Spider: A Tale from the Ashanti, by Gerald McDermott. The two had blue blocks, but they wanted something that moved and looked like a river.

“Who has had a similar problem?” Alisha asks. “You want to play something, but you don’t have what you need?” (Demonstrate high-order thinking.) Many children raise their hands. Weaving the success criteria into the day’s learning intention, Alisha continues, “Today, we’re going to learn how to use our words and actions to help pretend something is a tool or a material that we don’t have. You might already know what’s missing and say this when you share your plan. Or you might discover something is missing as you work, and then you’ll need to talk with your friends to adjust your plan and make decisions.”

To practice solving this kind of problem, Alisha introduces a game called This Isn’t a Stick. Children take turns holding a wooden stick (use visuals) and saying, “This isn’t a stick; it’s a ______.” They use gestures to act out different objects, with the stick becoming an oar, a snake, a steering wheel, and more.

Next, Alisha uses the routine of Plan-Do-Review to scaffold this new learning. (Provide scaffolds.) As children plan what they will use for pretend tools and materials, Khalil and Nestor decide to return to their play from yesterday. “We’re going to tell Anansi the Spider again,” they say. “We’ll look for something that moves like a river.”

Children go to centers and enact their plans. Alisha interacts with each group of learners, using questions to help them connect to the what, why, and how of learning. When she joins Khalil and Nestor, she asks, “What are you working on?”

Khalil explains that he is using blocks to build the various locations in Anansi the Spider. Nestor sifts through the materials tub and says, “I’m looking for a pretend river.”

“You’ve made your plan,” Alisha says, “and now you’re using your plan to make decisions about the materials you need. You need a pretend river. What would make that?” (Demonstrate high-order thinking.)

Nestor replies, “It has to move like a river. It can’t be hard like a block.”

Alisha deepens her questioning. (Demonstrate high-order thinking.) “I wonder what it looks like to move like a river. Can you make your arm move like a river?” Nestor makes wave motions with his arms. Alisha imitates this and thinks aloud, “Our arms are moving like a river. Our arms are . . . hmm . . . what motion is this?”

“They’re waves,” Khalil says. “They wiggle,” Nestor adds.

“What material could wiggle and flow like waves in a river?” Alisha asks.

Nestor pulls out a plastic necklace and dangles it. “This wiggles,” he says.

Khalil grabs another necklace and wiggles it along the ground. The two start making a pile of necklaces for the river.

“Our goal today is to pretend something is a tool or material that we don’t have, like in our game This Isn’t a Stick,” Alisha says. “What words and actions do you need to help you pretend those aren’t necklaces; they’re a river?” (Teach metacognitive skills.)

Khalil replies, “Well, I’m Anansi, but Nestor can make the river waves.” Nestor wiggles the necklaces while Khalil makes the spider fall into them. Nestor lets go of the necklaces suddenly and shouts, “Splash! I made the necklaces pop into the air!”

“You wiggled the necklaces and shouted ‘Splash!’ when you popped them into the air,” Alisha says. “It looks like you solved your problem by using your words and actions to pretend the necklaces are a river!” (Demonstrate high-order thinking.) Alisha exits their playful learning to join another group of children.

Clarity and Families

Communicating with clarity extends to families as well as learners. Our partnerships with families can help maximize children’s learning and development by building a two-way bridge between home and school (NAEYC 2019; Thunder et al. 2022)—we share and we listen.

Just like with our learners, we use the four essential strategies for communicating the what, why, and how of learning with families. To see this in action, we return to Kateri’s prekindergarten class.

Kateri’s class has engaged in an inquiry walk around the school yard. Using the familiar cognitive routine Notice, Wonder, and Create (Fetter 2011), the children have shared their noticings, wonderings, and collections of nature objects for their creations. Kateri wants to share with families the what, why, and how of learning so that they can extend this learning at home and Kateri can learn from them. She creates and shares with families a video, where she walks around her yard asking three questions and thinking aloud about her answers (use visuals):

Kateri’s class has engaged in an inquiry walk around the school yard. Using the familiar cognitive routine Notice, Wonder, and Create (Fetter 2011), the children have shared their noticings, wonderings, and collections of nature objects for their creations. Kateri wants to share with families the what, why, and how of learning so that they can extend this learning at home and Kateri can learn from them. She creates and shares with families a video, where she walks around her yard asking three questions and thinking aloud about her answers (use visuals):

Today, I’m being a scientist so that I can learn about living and nonliving things around my home. Scientists notice, wonder, and create. (Teach metacognitive skills.)

What do you notice? I notice things falling from the tree. They’re spinning and landing in the grass.

What do you wonder? I wonder, what are they? Why are they falling? What will happen to them? (Demonstrate high-order thinking.)

What can you create? I’m going to collect these. I’ll share what I make with you in another video.

Take a walk around as a scientist. What do you notice? What do you wonder? What can you create? (Provide scaffolds.) Take a picture or video and send it to me. I can’t wait to see and hear what you discover!

Families send Kateri videos and photos. One mother and daughter share a video of the daughter walking around their backyard touching plants while the mother names them in Arabic, their home language. Another family sends photos of siblings gathered around a rock collection that becomes a rock wall, a rock bridge, and then the prekindergartner’s name. A grandmother and two brothers send a photo of fruits and vegetables they noticed and wondered about while making a salad. Another family sends a photo of their seed collection.

Kateri learns so much from this exchange with families. She leverages their funds of knowledge, provides them with opportunities to connect to what their children are learning, and makes connections to children’s home languages and experiences. Communicating with clarity with families activates their roles as partners and co-evaluators who help children drive learning (Thunder et al. 2021).

Clarity from the Beginning

As illustrated in these early childhood classrooms, communicating with clarity helps children engage in and make meaning of their learning. By using intentional, language-based interactions across instructional modes and content areas, early childhood educators effectively communicate clarity in learning in ways that are meaningful, responsive, and accessible.

When educators make the what, why, and how of learning clear, children begin to take ownership over their learning journeys (Zimmerman 2001). To get started, we recommend educators identify what they are already doing to communicate with clarity and what an actionable next step would be, based on these reflection questions:

- How do I integrate and sequence learning experiences?

- How do I identify what the new learning is, why it is important, and how I will know my children have mastered it?

- How do I communicate this to learners through language, objects, actions, images, and interactions?

- How do I empower children to use the what, why, and how of learning to drive their learning?

- How do I communicate the what, why, and how of learning to families so that we can partner to help every child grow?

Photographs: header © Getty Images; 1–5 courtesy of the authors

Copyright © 2024 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

Almarode, J., D. Fisher, K. Thunder, & N. Frey. 2021. The Success Criteria Playbook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

CAST. 2018. “Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 2.2.” udlguidelines.cast.org.

Corwin Visible Learning Plus. n.d. “Global Research Database.” Visible Learning MetaX. Accessed June 5, 2021. visiblelearningmetax.com.

Fetter, A. 2011. “Ever Wonder What They’d Notice?” Presentation, Ignite Talks at the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics Annual Conference, in Indianapolis, IN. April 15, 2011. youtube.com/watch?v=a-Fth6sOaRA.

Frey, N., D. Fisher, & J. Almarode. 2023. How Scaffolding Works: A Playbook for Supporting and Releasing Responsibility to Students. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

NAEYC. 2019. “Advancing Equity in Early Childhood Education.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/equity.

NAEYC. 2020. “Developmentally Appropriate Practice.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/dap/contents.

Titsworth, S., J.P. Mazer, A.K. Goodboy, S. Bolkan, & S.A. Myers. 2015. “Two Meta-Analyses Exploring the Relationship Between Teacher Clarity and Student Learning.” Communication Education 64 (4): 385–418.

Thunder, K., J. Almarode, A. Demchak, D. Fisher, & N. Frey. 2022. The Early Childhood Education Playbook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Thunder, K., J. Almarode, & J. Hattie. 2021. Visible Learning in Early Childhood Education. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Thunder, K., J. Hattie, J. Almarode, D. Fisher, N. Frey, & A. Demchak. 2023. “What Really Matters in Play?” Theory into Practice 62 (2): 115–26.

Vélez-Ibáñez, C.G., & J.B. Greenberg. 1992. “Formation and Transformation of Funds of Knowledge.” Anthropology and Education Quarterly 23 (4): 313–35.

Zimmerman, B.J. 2001. “Theories of Self-Regulated Learning and Academic Achievement: An Overview and Analysis.” In Self-Regulated Learning and Academic Achievement: Theoretical Perspectives, eds. B.J. Zimmerman & D.H. Schunk, 1–65. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kateri Thunder, PhD, has the pleasure of collaborating with learners and educators from school divisions around the world to translate research into practice. Kateri researches, writes, and presents on equity and access in education and the intersection of literacy and mathematics for teaching and learning. [email protected]

John T. Almarode, PhD, is a professor of education in the College of Education at James Madison University. He teaches in the Elementary Education and Inclusive Early Childhood Education programs. He has worked with schools and classrooms all across the globe and written extensively on what works best in teaching and learning. [email protected]

Douglas Fisher, PhD, is professor of educational leadership at San Diego State University. A former early intervention teacher, Doug was elected into the Reading Hall of Fame in 2022. He is the coauthor of The Teacher Clarity Playbook and How Scaffolding Works. [email protected]

Nancy Frey, PhD, is a professor of educational leadership at San Diego State University. She has written articles and leads an international project on early childhood education. [email protected]

Alisha Demchak, MEd, is an early childhood educator whose passion for improving reading outcomes for all learners is visible across her work. She works with preservice and in-service teachers to build their skill sets and confidence in evidence-based reading instruction.