When in Doubt, Reach Out: Teaming Strategies for Inclusive Early Childhood Settings

You are here

Genevieve, a new teacher in the toddler room at Caring Connections early childhood center, is excited to meet her coworkers and the children in her classroom. Genevieve’s first day is fun, yet exhausting, and she loves interacting with the children. Over the next several weeks, Genevieve spends time getting to know the children and their families. She enjoys learning about each child’s personality and their favorite activities.

Alex is a 2-year-old in Genevieve’s class. Alex currently receives early intervention services due to concerns with his communication and social and emotional development. Alex’s family has shared his Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP) with Joy, the director of Caring Connections, and Genevieve has reviewed it. Still, she has several questions, including how to help Alex play with his peers and communicate when he is upset. Dani, a speech-language pathologist, works with Alex every Thursday at the center, and Maura is an occupational therapist who sees Alex at home on Monday evenings. Genevieve knows that Alex’s family has a social worker as part of the team, but she doesn’t know when they meet.

Genevieve wants to support Alex’s participation in the classroom. She wants to work with the specialists, but she isn’t sure where to begin. She talks with Joy, and they decide to ask Alex’s parents, Audrey and Xavier, if they can schedule a meeting.

Today’s inclusive early childhood settings provide robust programs for all early learners, including those with disabilities or developmental delays, such as in the areas of motor, communication, or social and emotional development. Yet often, the families of these early learners worry that their children’s needs may not be met in an inclusive setting. Based on our combined 80-plus years as early interventionists, early childhood special educators, social workers, preschool teachers, professional development providers, and researchers, this article will provide an overview of early intervention services in a variety of settings. These strategies are intended to support novice teachers, preservice teachers, and any educator who seeks foundational, research-supported practices for working with infants and toddlers who have a delay or disability. Following Genevieve, Alex, and others from the opening vignette, we will weave strategies for fostering collaboration in inclusive early childhood settings by focusing on a child with delays in the social-emotional and communication domains.

An Overview of Early Intervention and Team Members

Early intervention is a federally supported program for families who have a child under 36 months of age with a developmental delay or disability (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act 2004). Early intervention may not always look the same across states, but there are some common characteristics:

- A service coordinator is responsible for ensuring that each eligible child receives all the services listed on their Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP).

- The IFSP includes the child’s developmental levels, family-identified outcomes, the services for which the child is eligible that will assist with meeting those outcomes, and the service providers who will support the family.

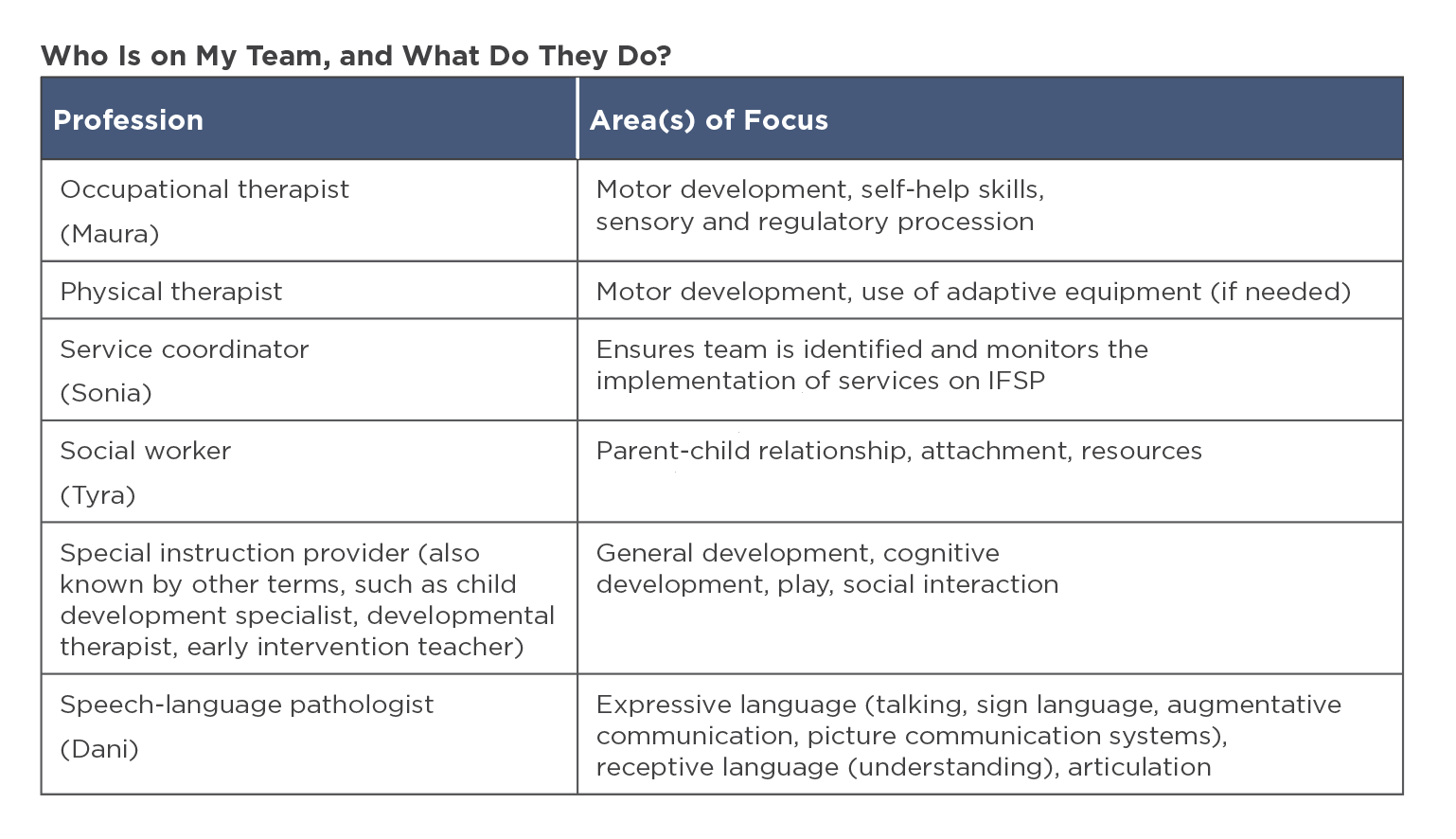

- Early interventionists form a team to support the family in meeting IFSP outcomes. (See “Who is on My Team, and What Do They Do?” below for information about potential team members.)

In some states, one team member is assigned as the primary person to work with a family, with guidance and contributions from other team members. In other states, multiple team members work with the child and family on a regular basis. Regardless of the service model, early interventionists work around a child’s daily and weekly routines, both at home and in the community. They partner with the family and with community entities to support the family in meeting IFSP outcomes (Pletcher & Younggren 2013). For example, an IFSP outcome could include being able to express wants and needs verbally or by using an alternative communication system, or it could include being able to participate in mealtime routines with the family. Each IFSP will list child- and family-specific strategies to help meet the outcomes; strategies will not be the same for different families even if the overarching outcome is similar.

Inclusive Settings for Young Children

Inclusive settings are those that include children with and without disabilities. Children with developmental delays or disabilities participate in many inclusive community activities, such as early learning programs, park district programs, and library story times. The defining features of inclusive programs for young children include access to community settings, full and active participation in the activities within those environments, and administrative supports necessary for participation (DEC/NAEYC 2009). Strong and consistent collaboration among educators, early interventionists, and family members is necessary for high-quality inclusion (NPDCI 2009). Therefore, effective strategies for teaming and collaboration are essential.

While early childhood educators have the willingness to support young children with disabilities, they and their programs may not have the knowledge, past experiences, or sufficient means to individualize instruction (Yu 2019). For example, although this trend is changing to include more extensive coursework, in the past, educator preparation programs may have included just one or two courses in special education, often at an introductory level (Rakap et al. 2017). Having access to consultation and other resources helps educators view inclusion more positively, and it also creates positive experiences for the child (Knoche et al. 2006; Huang & Diamond 2009; Muccio et al. 2014). Opportunities for collaboration among professionals within the field are as necessary as the collaboration between those professionals and the family.

For example, to ensure that Alex fully engages in Genevieve’s classroom, ongoing and individualized assistance is essential. This will be provided by Alex’s family, his early intervention team, and Genevieve. Additionally, as the center director, Joy can offer the time and resources for Genevieve to participate in professional development and to plan, consult, and reflect with other members of Alex’s team.

Elements of Effective Communication and Collaboration

Early childhood educators in both center- and home-based settings can team with early interventionists. Indeed, participating as a team member on a child’s IFSP is a vital step toward effective collaboration. For a child with a disability to succeed in an inclusive classroom, continual communication and regular meetings are critical. When all the members of a team—including the family—work together, individualized services are consistent across multiple settings. Children who receive supports in multiple settings have interconnected opportunities to practice and make progress on skills that enhance their engagement in everyday routines and learning experiences (McWilliam 2011). Each member of the team plays a role in collaboration and communication so that a child experiences appropriate adaptations and strategies for positive learning and growth to occur (Murata & Tan 2009; Vakil et al. 2009; Hart Barnett & O’shaugnessy 2015).

Strategies for Effective Communication and Collaboration

Because of the number of individuals on an IFSP team, efficient communication can seem overwhelming or difficult to achieve. Five key strategies can overcome these challenges and foster effective communication, which can in turn lead to fruitful collaboration. These factors are: defining roles, exchanging information across settings after gaining consent, utilizing communication logs, scheduling meetings, and gathering and using data.

Defining Roles

Genevieve knows that Alex and his family are supported by several professionals, but she is not sure about each person’s unique role and focus with Alex. Genevieve is particularly confused with outcomes related to Alex’s social and emotional development. She would like clarification on the strategies that Maura suggests and how these are similar to or different from the information Tyra, the social worker, is sharing with Alex’s family. Also, Genevieve is unsure of what interaction Sonia, the service coordinator, has with the rest of the team. As Genevieve reviews Alex’s IFSP, she makes notes of questions that she will ask Audrey and Xavier when she has the opportunity to discuss the plan and people involved.

Everyone working on a team has a role, but this may not be readily evident. Some roles are clear, such as the speech-language pathologist who is responsible for providing strategies, activities, and materials to promote language and communication. Other roles, such as social work or occupational therapy, may be unclear, so establishing responsibilities in the initial stages of an IFSP prevents confusion and ensures that follow-through occurs in all areas.

Exchanging information

When Genevieve first meets with Alex’s family, she asks them to complete the necessary consent forms for her center. She also asks the family to sign consents with all of Alex’s early interventionists so she can discuss Alex’s goals and progress with everyone on the team. She shares with the family information about the daily class schedule and ideas that she has to help Alex feel part of the classroom. She mentions that there may occasionally be classroom visitors and asks for input from Alex’s parents on how to make sure Alex is comfortable with new people. Genevieve also informs Audrey and Xavier that Joy is very supportive and has provided her with information and resources. Additionally, she plans to take a short class on inclusion and hopes to learn more about supporting children with developmental delays.

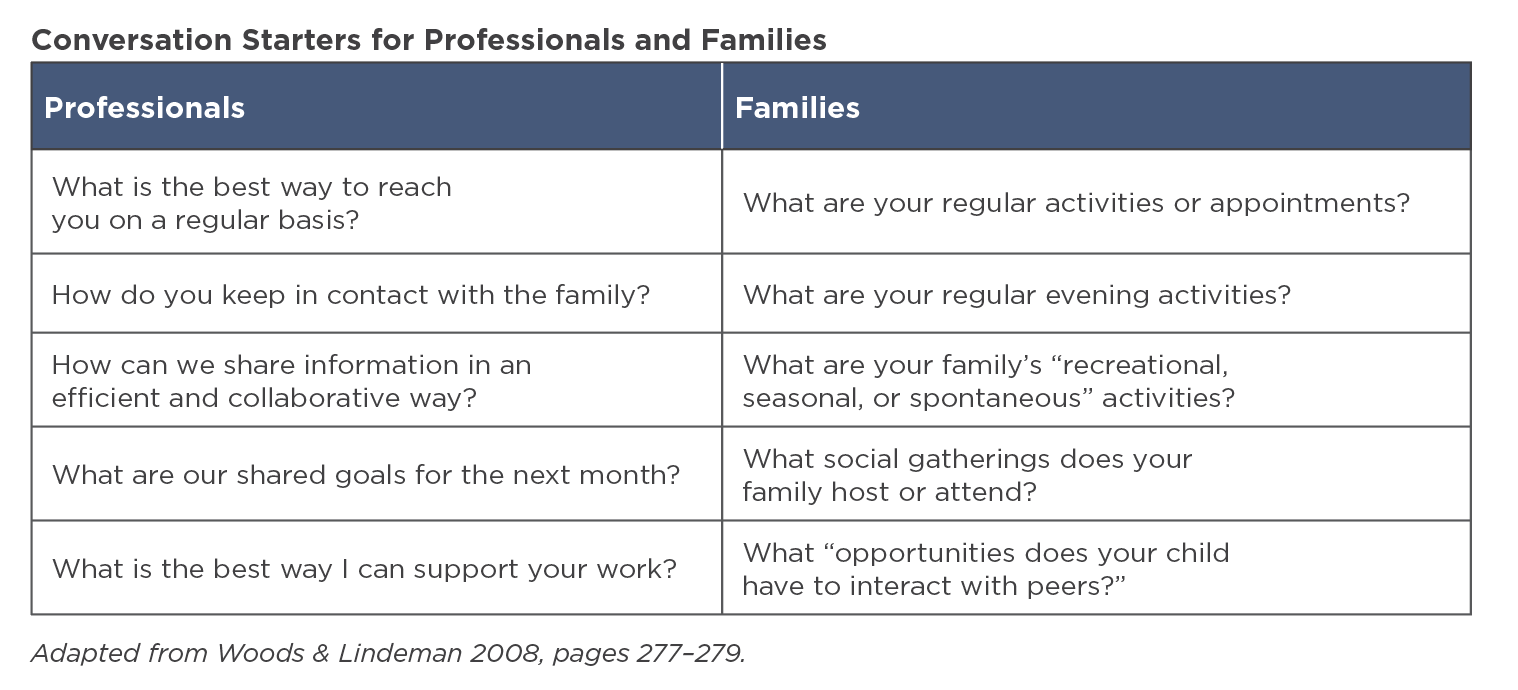

Once she obtains consent and has the appropriate contact information, she asks each team member questions, such as their preferred means of communication, the frequency with which they would like to communicate, and the best times of day to communicate via phone, email, or in person. During these conversations, Genevieve also inquires about service delivery and gathers more information related to Alex’s development. She’ll use this information to plan activities in the classroom.

Because Genevieve is relatively unfamiliar with the IFSP process, she asks questions related to it. Genevieve notices that a particular strategy listed on the IFSP—providing Alex a quiet space with no distractions—will not work in the classroom setting, so she invites Maura, the occupational therapist, to observe. Together, they brainstorm alternative strategies and ideas. These include having soothing and familiar objects available for Alex and rearranging the classroom so he has a space he can safely go to when he is overwhelmed. Both Genevieve and Maura feel like this visit in the classroom created an opportunity for more meaningful collaboration to occur, and Alex’s parents are excited to learn about the conversation between the two. They support the strategies identified through this collaboration.

Effective communication depends upon having consent to share information among members of the IFSP team and other important adults in the child’s daily life. Early interventionists and educators must receive consent from the child’s legal guardian for this to happen. It is important to understand which consent forms are necessary within an organization, and also to learn what consent forms are needed from other providers on the team. Many times, a release of information needs to be completed for all team members who plan to communicate. If parental consent to share information is difficult to obtain, team members should listen to the family’s concerns and have an open conversation about why consent to exchanging this information will help the child. Often, concerns are alleviated by explaining who will have access to what types of information and how it will be used. Parents should know that they can revoke consent at any time.

Once consent forms have been signed, team members should identify the best way to communicate with each other. (See “Conversation Starters for Professionals and Families” above for some sample conversation starters to use when gathering information from families and other team members.) With that information, each team member can regularly call, text, or email each other. They also can observe how the child learns and interacts with others in a variety of settings. Because each team member is working toward the same goals and outcomes—but providing different services to reach these goals—all team members can seek understanding about service delivery and the child’s needs, strengths, interests, and other assets shown in different contexts or settings.

Using Communication Logs

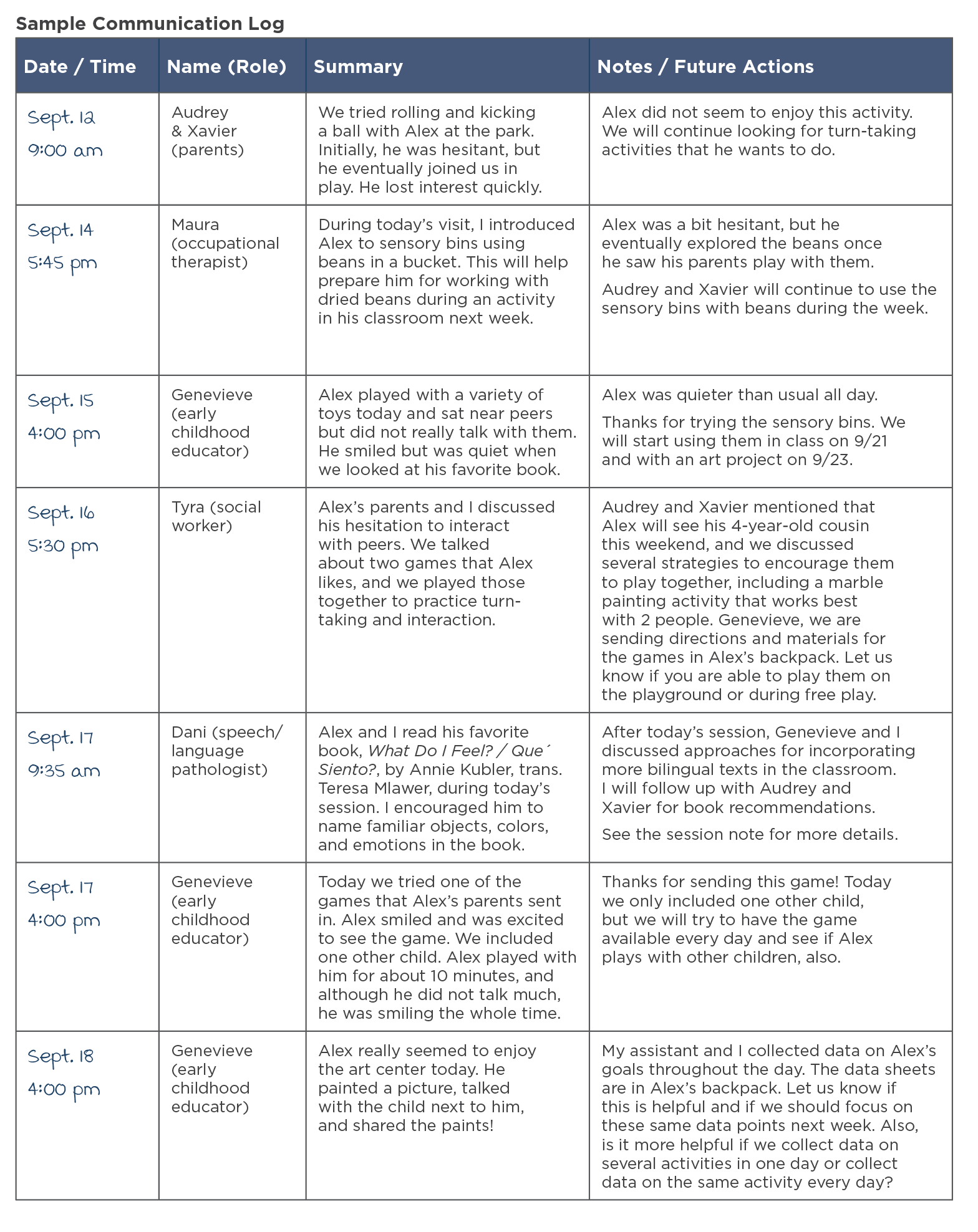

Alex has a large team, and Genevieve finds herself communicating with many different people. She recalls that Alex’s parents expressed a preference for communication to be on paper. It allows them to write information more easily, rather than having to remember to log into a website with a digital notebook. So Genevieve uses a paper notebook to begin a communication log. After each conversation with a team member, she documents the date, time, and person she spoke with, along with a brief summary of the discussion. The communication log is stored in Alex’s backpack in his cubby.

Genevieve herself comes to rely on the communication log as a reference for her notes and ongoing planning. Other team members use it to catch up on what has happened during the day at the center. Tyra (the social worker) usually sees Alex and his family at home but she occasionally visits Caring Connections to assist Alex there. When she does, she communicates face-to-face with Genevieve as well as in the notebook. Alex’s parents also contribute to the conversation by writing in the log so that the other team members know what is working well at home and in community settings. Joy helps in these efforts by providing Genevieve time during the day to write in the notebook and read what others wrote.

Because teams include multiple members, a clear and agreed-upon communication strategy encourages all team members to contribute and stay informed. It also ensures that the sole responsibility for sharing information does not rest on just one person, particularly the parent. This communication system can be physical (a spiral notebook) or digital (a shared document on a password-protected account). The primary considerations are ease of use and privacy. (See “Sample Communication Log” below for an example of a communication log used with multiple team members.)

Scheduling Regular Meetings with All Team Members

Alex’s family or any team member may request an IFSP meeting to discuss concerns. These may include, but are not limited to, a drastic change in Alex’s behavior or functioning, a need to revise IFSP outcomes, a lack of communication with specific providers, or ineffective collaboration among all providers. After Genevieve’s first IFSP meeting with Alex’s team, she feels that she understands the early intervention process better, including why the specific outcomes were chosen for him. She is also able to meet and ask questions of the social worker, Tyra, and service coordinator, Sonia. Genevieve is excited to share her observations of Alex’s language, emotional, and social skills in the classroom, such as when he attempted to comfort a peer who fell on the playground. The other team members appreciate her input.

While communication among the family, early learning program, and early intervention providers should occur on a regular basis, convening a formal IFSP meeting offers the time and space for everyone to meet together. During an initial IFSP meeting, introductions are vital, and this is an ideal time to decide on preferred methods of communication, as highlighted earlier. Meetings to review and revise the IFSP goals and outcomes are typically held every six months, but they can be requested at any other time (IDEA 2004). The IFSP meeting is where family-centered functional outcomes are determined; therefore, all team members should be present and asked for input during this meeting. With parental consent, early childhood educators can be present at the IFSP meeting. They have essential information regarding the child’s skills, strengths, and areas of concern in the classroom and with peers. If an outcome listed on the IFSP is no longer appropriate, a meeting can be convened to revise the IFSP.

Gathering and Using Data

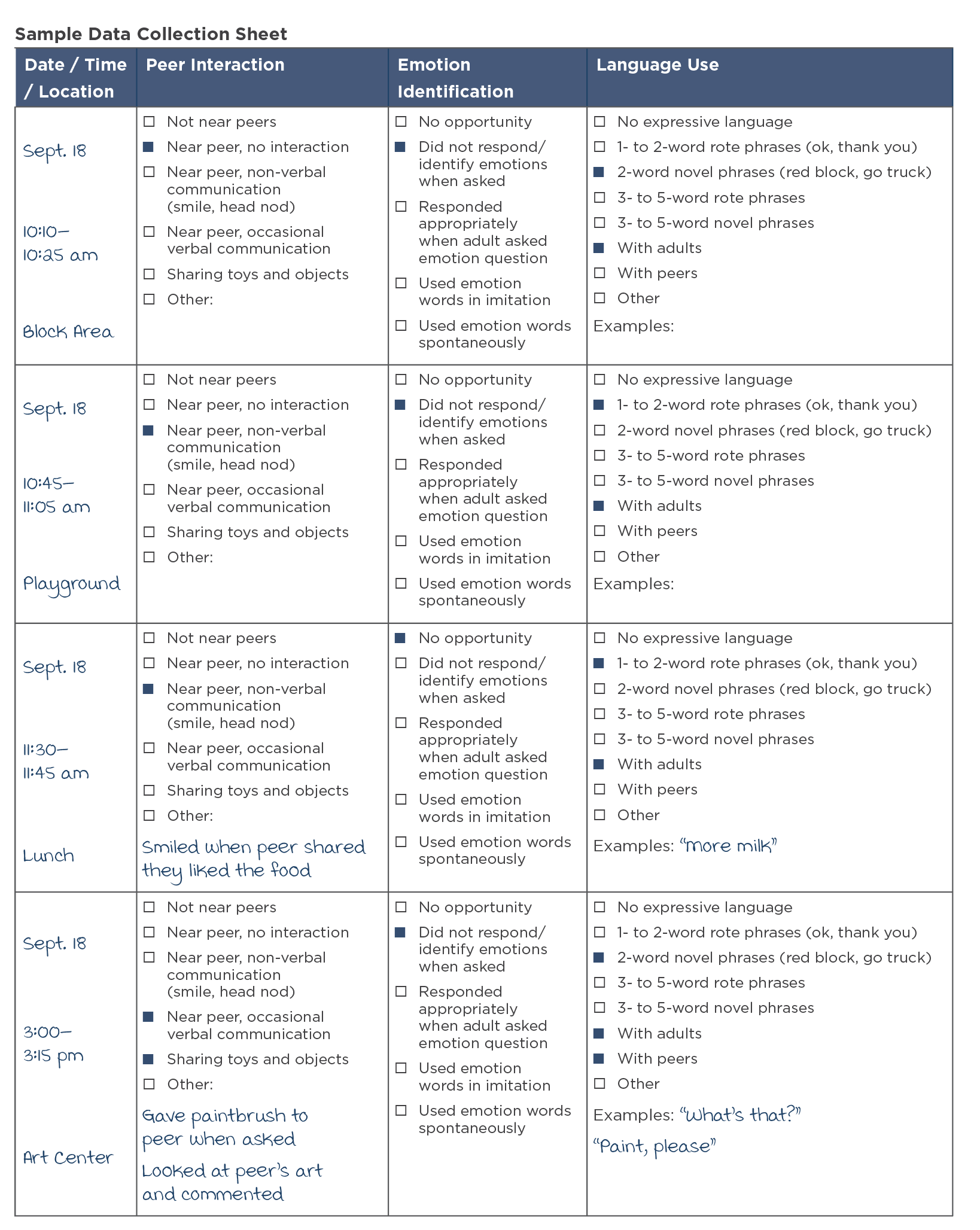

Initially, Genevieve is concerned with the amount of time it will take her to collect data related to Alex’s outcomes. She wants to find ways to authentically collect data within her setting. For example, Alex has outcomes related to participating in parallel play during structured and unstructured play time in familiar settings. He also has outcomes related to identifying basic emotions (happy, sad, angry, etc.) when looking at books or playing.

Genevieve and Tyra work together to create a data sheet for the target behaviors so that any adult in the classroom can easily and quickly fill it out. With these sheets available, Genevieve has data by the end of each day on Alex’s play, social, emotional, and communication behaviors related to his outcomes.

Within the home setting, Tyra works with Alex’s family to further support their development of positive, nurturing, and responsive parenting practices to help increase Alex’s emotion regulation. The family is also encouraged to openly validate Alex’s experiences and label his emotions throughout the day. During each session, Tyra, Audrey, and Xavier discuss the priority for the week and how they will keep data. Some weeks, Audrey and Xavier write a brief note at the end of each day related to how Alex responded to stressful or new situations. Other weeks, they keep track of how many times Alex was able to identify emotions in books that they read each day. Audrey and Xavier share this information with the rest of the team in the communication notebook.

Because each team member collects and shares data about Alex’s outcomes, this information can be used to compare his behaviors across settings and to help inform service delivery.

Family-identified outcomes are a key component of the IFSP document. As such, everyone on a child’s team works toward meeting these specified goals, and collecting data across settings is critical. Such information helps to guide service delivery, to demonstrate that the child is making progress toward their IFSP goals and outcomes, and to determine how a child is responding to interventions. Educators readily acknowledge the importance of data, but even for those with years of experience, the process of data collection can be difficult: There may be insufficient time to collect it. Recording sheets and systems may not be appropriate for the child’s goals or easy to use. Team members may collect data inconsistently with each other. (Browley & Stormont 2014; Zweig et al. 2015; Ruble et al. 2018).

Owing to the many different ways to take data, each team member should communicate early on about effective ways to gather data for their settings and purposes. Within an early childhood setting, educators can use anecdotal notes, running records, rating scales, or frequency counts (Classen & Cheatham 2015; Bates et al. 2019; Love et al. 2019). Teams should decide on the best mechanism for collecting and sharing data that will be easy, useful, and lead to information about progress toward identified outcomes. (See “Sample Data Collection Sheet” above for an example of a data recording sheet created for use in an early learning setting.)

All Team Members Have a Voice

Many effective strategies can be used when educating and caring for infants and toddlers with delays or disabilities in a variety of inclusive settings. Optimal teaming relies on shared responsibility among early interventionists, early childhood educators, administrators, and families. All team members should reach out to one another in order to appropriately support the child across daily routines and activities. (See “Resources for Professionals and Families” below for a list of resources.) All team members have a voice; when in doubt, reach out!

As Genevieve’s year draws to a close, she marvels at the progress Alex has made. His communication skills are improving; he routinely engages in parallel play; he has even started identifying specific emotions and interacting more regularly with one or two particular friends from class. Alex’s team continues gathering data and meeting regularly. His family remains an involved, integral part of his team.

Genevieve recalls how uncertain she was when the year began. As a new teacher, she doubted her classroom expertise and underestimated the value her voice and observations would have amid a much more experienced group of professionals. Now, she sees the integral role she played in Alex’s progress. Thanks to the team’s collaboration and the ongoing and consistent communication among all of its members, she ends the year knowing that she is armed with tools and support that will guide her in shaping the lives and outcomes of future students.

Resources for Professionals and Families

Policy and Position Statements

-

Policy statement on Inclusion of Children with Disabilities in Early Childhood Programs

This document provides strategies and information for state and local programs to consider when creating inclusive early childhood settings and programs. -

Early Childhood Inclusion. A joint position statement by the Division of Early Childhood (DEC) and the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC)

This document discusses the importance of inclusion and discusses three components (access, participation, and supports) for high-quality inclusive environments. -

DEC Recommended Practices

This website provides many resources related to the DEC Recommended Practices, which describe what early childhood educators should include as the foundation of their work with children and families.

Videos and Training Materials

-

“Early Intervention and Child Care: Natural Partners in Natural Environments”; Supplement Packet available here.

This video showcases child care providers and early interventionists working together to support infants and toddlers; the accompanying packet provides information and strategies. -

CONNECT Courses, “Foundations of Inclusion”

This self-paced online course provides an introduction to inclusive practices for early childhood environments. The site also includes modules that describe additional practices such as teaming and collaboration or dialogic reading. -

Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center, “Practice Improvement Tools: Using the DEC Recommended Practices”

This website includes resources to use in conjunction with the Recommended Practices. The checklists provide a quick description of what a provider should do; the illustrations are short videos showing the practices in action; the practice guides provide a description of how to implement the practices. -

“Results Matters Video Library—Just Being Kids”

The videos in this collection show young children and their families collaborating with early interventionists in homes and a variety of community settings.

References

Bates, C.C., S.M. Schenck, & H.J. Hoover. 2019. “Anecdotal Records: Practical Strategies for Taking Meaningful Notes.” Young Children 74 (3) 14–19.

Browley, S., & M.A. Stormont. 2014. “Investigating Reported Data Practices in Early Childhood: An Exploratory Study.” Journal of Positive Behavior Intervention 16: 102–111.

Classen, A., & G.A. Cheatham. 2015. “Systematic Monitoring of Young Children’s Social-Emotional Competence and Challenging Behaviors.” Young Exceptional Children 18 (2): 29–47.

DEC (Division for Early Childhood), & NAEYC (National Association for the Education of Young Children). 2009. Early Childhood Inclusion: A Joint Position Statement of the Division for Early Childhood (DEC) and the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC). Position statement. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute.

Hart Barnett, J.E., & O’shaughnessy, K. 2015. “Enhancing Collaboration Between Occupational Therapists and Early Childhood Educators Working with Children on the Autism Spectrum.” Early Childhood Education Journal 43: 467–472.

Huang, H., & K.E. Diamond. 2009. “Early Childhood Teachers’ Ideas about Including Children with Disabilities in Programmes Designed for Typically Developing Children.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 56: 169–182.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. 2004. 20 U.S.C. § 1400.

Knoche, L., C.A. Peterson, C.P. Edwards, & H. Jeon. 2006. “Child Care for Children With and Without Disabilities: The Provider, Observer, and Parent Perspectives.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 21: 93–109.

Love, H. R., E. Horn, & Z. An. 2019. “Teaching Observational Data Collection to Early Childhood Preservice Educators.” Teacher Education and Special Education 42: 297–319.

McWilliam, R.A. 2011. “The Top 10 Mistakes in Early Intervention in Natural Environments – and the Solutions.” ZERO TO THREE 31 (4): 11–16.

Muccio, L. S., J.K. Kidd, C.S. White, & M.S. Burns. 2014. “Head Start Instructional Professionals’ Inclusion Perceptions and Practices.” Topics in Early Childhood Special Education 34: 40–48.

Murata, N.M., & C.A. Tan. 2009. “Collaborative Teaching of Motor Skills for Preschoolers with Developmental Delays.” Early Childhood Education Journal 36: 483–489.

NPDCI (National Professional Development Center on Inclusion). 2009. Research Synthesis Points on Early Childhood Inclusion. Summary. Chapel Hill: NPDCI.

Odom, S.L., J. Vitztum, M. Wolery, J. Lieber, S. Sandall, M.J. Hanson, P. Beckman, I. Schwartz, & E. Horn. 2004. “Preschool Inclusion in the United States: A Review of Research from an Ecological Systems Perspective.” Research in Special Educational Needs 4: 17–49.

Pletcher, L.C., & N.O. Younggren. 2013. The Early Intervention Workbook: Essential Practices for Quality Services. Baltimore: Brookes Publishing

Rakap, S., O. Cig, & A. Parlak‐Rakap. 2017. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 17 (2).

Ruble, L.A., J.H. McGrew, W.H. Wong, & K.N. Missall. 2018. “Special Education Teachers’ Perceptions and Intentions Toward Data Collection.” Journal of Early Intervention 40: 177–191.

Vakil, S., E. Welton, B. O’Connor, & L.S. Kline. 2009. “Inclusion Means Everyone! The Role of the Early Childhood Educator when Including Young Children with Autism in the Classroom.” Early Childhood Education Journal 36: 321–326.

Woods, J.J., & D.P. Lindeman. 2008. “Gathering and Giving Information with Families.” Infants & Young Children 21 (4): 272–284.

Yu, S. 2019. “Head Start Teachers’ Attitudes and Perceived Competence Toward Inclusion.” Journal of Early Intervention 41: 30–43.

Zweig, J., C.W. Irwin, J.F. Kook, & J. Cox. 2015. Data Collection and Use in Early Childhood Education Programs: Evidence from the Northeast Region (REL 2015–084). Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Northeast & Islands. Retrieved from http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs.

Photographs: © Getty Images

Copyright © 2021 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

Christine M. Spence, PhD, is an assistant professor of special education at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, Virginia. Christine has worked in early intervention as a music therapist, developmental therapist, and professional development provider. Her research focuses on supporting families to access high-quality services across systems. [email protected]

Deserai Miller, PhD, LCSW, is currently an instructor at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. She has a broad range of research, teaching and practice experiences related to her primary area of focus: the provision of supports for young children who have experienced trauma.

Catherine Corr, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Special Education at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. She has worked in early intervention and preschool settings. Her research focuses on supporting young children with disabilities in multiple service systems. [email protected]

Rosa Milagros Santos, PhD, is professor of special education at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. Her research interests focus on services for infants, toddlers, and preschoolers with disabilities and the preparation of personnel to work with young children and families from diverse backgrounds. [email protected]

Brandie Bentley, MSW, is a third-year PhD student in the Social Work Department at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. [email protected]