"How Do You Spell Butterfly?" Connecting Play to Content Learning

You are here

Play is vital to life and learning, yet many preschool settings have increased teacher-led, academic instruction at the expense of play. While this new focus aims to prepare children for the high-stakes testing they will face in future schooling, it can be at odds with the foundational considerations, principles, and guidelines of developmentally appropriate practice. It also goes against what many researchers and practitioners know about young children—that play supports their development and learning across the curriculum and helps prepare them for later learning and academic success.

Put another way, play and content learning are not mutually exclusive. When given time, space, responsive supports, and materials to explore, children will seek opportunities that advance their critical thinking skills, content knowledge, and active engagement in learning. As pointed out in NAEYC publications on developmentally appropriate practice, playful experiences—both self-directed and teacher-guided—offer a powerful context for content-rich learning.

Bing Nursery School is the laboratory school for Stanford University’s School of Humanities and Sciences, serving children ages 2 to 5. I have worked there as a teacher for the past 10 years. Using thoughtfully curated and scaffolded activities, we (the teachers at Bing) create playful environments that help children build the foundational skills they will need to meet future state and national learning standards. The following are just a few examples of how I and other teachers at Bing use open-ended materials with intentional teacher planning and scaffolding to engage children in active thinking, social interactions, and joyful learning across multiple content areas.

Painting and Literacy

Drawing and painting are a big part of Teacher Jenna’s 3- to 5-year-old class. Each day, she sets out easels, paper, and a variety of paints and paintbrushes for her class to explore. Children paint letters, pictures, and representations of what they see and do in the classroom.

For instance, the children are eagerly awaiting the emergence of their class butterflies. Often, during free-play time, Jenna pulls out the net enclosure that contains a handful of chrysalises and invites the children to draw what they see. As they do, she quietly points out features, remarks on the children’s efforts, and writes down their thoughts and questions.

When the butterflies finally emerge from their chrysalises, Mateusz wants to remember the moment. He goes to the art area and begins to paint.

“How do you spell butterfly?” he asks Jenna. She reminds him that a classmate is nearby and can likely help. The two begin working together to practice their invented spelling, eventually painting “BDRFLI” on the paper.

Teachers can intentionally set the stage for literacy learning by giving children a variety of ways to express themselves. Rather than dictate what children draw or paint, they can invite children to record events and tell stories or factual information as part of their play. I did this by building on my children’s interest in the class butterflies.

Through experiences with writing and painting, children acquire a variety of literacy skills. These include manipulating a paintbrush as a writing tool; playing with the appearance of print as they explore color, lines, patterns, and symmetry; and developing letter-sound correspondence as they sound out the titles of their works and write them down.

When frustrations arise as children tackle new skills, teachers can scaffold their learning in multiple ways. They might bring out a smaller paintbrush for detail work like writing, or they might help children shape letters. Teachers can also invite in a more experienced classmate to help—as I did with Mateusz.

Water and Measurement

Water play is available every day at Bing for children’s exploration. One week, Jenna sets up the water table with an A-frame climber nearby. She places gutters at various angles between the two. Inside the water table are a variety of bottles, cups, and graduated cylinders.

Four-year-old Noosha experiments with the water and gutters. “When you pour, the water goes down,” she tells Jenna as she pours water from the top of one gutter and watches it run into the water table.

Noosha then experiments with the materials in the water table, counting aloud as she pours and noting which ones “pour for longer.” Jenna counts with her and articulates Noosha’s method of determining which container holds more water: the longer they pour, the more water they hold. Noosha notices that the largest volume is not exclusive to one type of container. She begins sorting the bottles, cups, and cylinders—once by height, then by width, and finally by container type.

Teachers can create a more meaningful experience by focusing on specific content objectives and materials. The gutters and containers in my water table, for example, prompted children to describe and compare the measurable attributes of objects; classify and sort those objects; and investigate properties like temperature, color, pressure, and flow.

When a teacher is present to support water play, they can ask questions to get children talking and pose problems for them to solve together. This encourages children to participate in collaborative conversations. It also prepares them for future learning as they integrate math, language, and physical exploration in increasingly complex ways.

Blocks and Symbolic Representation

The block area is a focal point of Jenna’s classroom, drawing children from various areas throughout the day. Today, two 4-year-olds, Tiago and Avi, are building with small table blocks when they realize how similar they are to the class’s unit blocks. Jenna wonders aloud whether the two could build the same structure with unit blocks.

The block area is a focal point of Jenna’s classroom, drawing children from various areas throughout the day. Today, two 4-year-olds, Tiago and Avi, are building with small table blocks when they realize how similar they are to the class’s unit blocks. Jenna wonders aloud whether the two could build the same structure with unit blocks.

Using their initial structure as a model, they begin building again, looking back at the table frequently and traversing the space several times to get a closer look. Tiago focuses his attention on balancing larger blocks on their ends and bridging the space between them with a single unit block. As they work, the two narrate how many blocks are still needed and which ones they are. They repeat this process with increasingly difficult structures throughout the morning and welcome others to join them.

Among other skills, block play provides opportunities for children to act out ideas and work with variables such as texture, weight, and balance. As they build, children must consider measurement and spatial relationships as well as symbolic representation, symmetry, addition, and subtraction.

As seen in the vignette, I positioned the table block area near the unit blocks and used an “I wonder” statement to prompt Tiago and Avi to extend their play. I could have offered additional options and supports by setting up a table block structure to inspire creations or by building a structure on the carpet as a more overt invitation.

Sand and Signage

The large outdoor sand pool at Bing supplies endless opportunities for large body and sensory play. Today, Jenna extends the learning by introducing materials that are traditionally used inside. She sets colored paper on a table at the edge of the sand area, along with writing utensils, tape, and craft sticks.

The large outdoor sand pool at Bing supplies endless opportunities for large body and sensory play. Today, Jenna extends the learning by introducing materials that are traditionally used inside. She sets colored paper on a table at the edge of the sand area, along with writing utensils, tape, and craft sticks.

Several children work tirelessly to dig the “deepest hole they’ve ever seen.” This attracts more children to check it out. The newcomers worry that children could fall in and get hurt. Jenna suggests that someone make a sign to warn newcomers about what is happening.

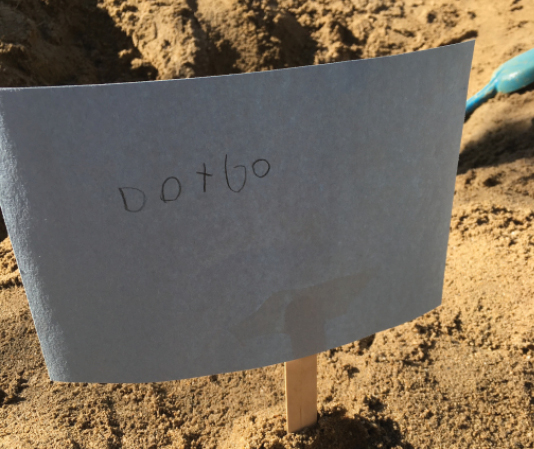

Four-year-old Julian finishes his sign and tells Jenna, “I made a hole sign for you. It’s warning people that there’s a big, deep hole.” The sign offers a pictorial representation rather than words. This inspires Nathan, another 4-year-old, to use invented spelling to make his own sign. “It says, ‘Don’t go.’ Don’t go in that hole because it’s too deep. You’ll get hurt.”

Sand is a natural, readily available, open-ended material with rich sensory and tactile properties. While it has many benefits for learning and development, teachers can intentionally modify it to support specific content area skills.

For instance, knowing that children often seek to share and preserve their work by making signs, I introduced paper, tape, sticks, and pencils to the sand area. This encouraged children to write to inform others and narrate the events they observed. Through repeated exploration, they learned to use a combination of drawing, dictating, and writing for these purposes.

Clay and Repeated Experiences

Clay is available at Bing every day for children to explore, often independently. On this day, Jenna has set it out with the intention of being a coplayer. She has in mind 4-year-old Julia, who has been struggling to draw and cut heart shapes. Jenna invites Julia to try using the clay to create hearts.

As they both begin pressing, rolling, and shaping the clay, Julia describes in great detail how she wants her heart to look. She presses and shapes the clay over and over until she has created a solid heart shape. Satisfied, she moves on to represent a heart in another way. This time, she uses a long coil of clay to create the heart’s outline.

Through working with clay, children are able to solve problems with materials, develop fine motor skills, create representations of real shapes and objects, and verbally describe them. I knew that using clay would provide Julia the chance to create over and over, with the opportunity to change or improve her design each time.

Clay can be a challenging material for small hands, so teachers may need to model how to work with it. As children become more confident in their abilities, their ideas come to life as they begin to replicate the objects and experiences in their lives.

Conclusion

Test-based accountability and the pressure to perform academically have set “play” and “learning” at odds. But as these vignettes show, the two are not mutually exclusive. Play facilitates content learning when teachers are intentional about setting up, supporting, and observing and documenting content-rich, playful environments and activities. Nurturing children’s playful and curious spirits leads to natural, relevant, and remembered learning, setting them up for success in kindergarten and beyond.

Communicating the Value of Play to Families

“But he just spends all day in the sand. What can he possibly be learning?”

This question (and others like it) may be heard frequently in play-based programs. Rather than dismissing it, teachers can view it as an opportunity to help families see the value that play in the early years has for later academic and life success.

To communicate what children are learning during play, educators can connect a play experience to one or two child development domains (physical, cognitive, social, emotional, and/or linguistic). They can also share with families the specific skills a child is learning and how those relate to content standards. The goal is to communicate what competencies a given play event demonstrates, how teachers supported and enhanced the experience, and how family members can continue the exploration at home.

Photographs: courtesy of the author

Copyright © 2022 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See permissions and reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

This article supports the following NAEYC Early Learning Programs standards and topics

This article supports the following NAEYC Early Learning Programs standards and topics

Standard 3: Teaching

3A: Designing Enriched Learning Environments

3G: Using Instruction to Deepen Children’s Understanding and Building Their Skills and Knowledge

Jenna Valasek is a teacher at Bing Nursery School and a lecturer for the Psychology Department at Stanford University in Stanford, California.