Rocking and Rolling. Using Materials Creatively to Enhance Toddler Learning Environments

You are here

As coaches with the infant-toddler Child Development Associate (CDA) program at the University of Nevada, Reno Extension, we provide infant-toddler teachers in Nevada with specific professional development to successfully meet the CDA assessment process and enhance the quality of their classrooms. During the past seven years, we have had the opportunity to coach, train, and partner with several hundred teachers and to assess their learning settings. We have listened to educators share their concerns about children’s lack of engagement with materials in their settings and have partnered with them to find solutions.

In this article, we offer three strategies we have found helpful for enhancing toddlers’ learning environments. These are

- following children’s interests

- using repurposed materials

- including loose parts in learning spaces

To illustrate these strategies in action and discuss ways to involve families, we share the journey of Ava, an educator of 2-year-olds, as she discovers how to use materials creatively to enhance her learning environment.

The Role of the Learning Environment

A learning environment that fosters children’s sense of belonging, purpose, and agency is part of developmentally appropriate practice (NAEYC 2020). High-quality environments reflect the social and cultural contexts of the children being served. Educators are responsive, notice children’s strengths or assets and interests, and design meaningful learning experiences based upon them (La Paro & Gloeckler 2016). This includes following children’s leads in identifying materials that will expand their imaginations and enhance their cognitive, social and emotional, and physical development (Rentzou 2014).

Deviney and colleagues state that “growing an inspiring and magical environment for young children is much like growing a seed into a beautiful flower” (2010, 9). Early childhood educators can plant these seeds by asking how their settings’ materials will help them connect to and build relationships with the children who engage there (NAEYC 2020). They must think of ways to create learning spaces that intrigue children and draw their attention.

Open-ended items invite children to explore an area independently (Shrier 2016). Children are more likely to engage in spaces where accessible materials appear enticing and provoke their curiosity (Lagiou et al. 2021). In the next sections, we follow Ava as she uses specific strategies to create an environment that elicits the engagement of toddlers in her classroom.

Follow Children’s Interests

During a coaching session, Ava shares her concerns about children’s lack of engagement in her classroom. Her coach, Robyn, invites Ava to closely observe the children’s play: Where do they currently play, and what types of materials keep their interest?

Ava notices that the 2-year-olds in her classroom are interested in collecting leaves, pinecones, twigs, and pebbles. She decides to follow this interest. While outside, she sets out baskets for the children to use as they collect materials from nature. Once collected, Ava plans a variety of activities that build upon the children’s curiosity and that introduce concepts and vocabulary related to nature, such as putting a name to the objects children see and using words like environment and habitat (Deviney et al. 2010). These activities include creating collages and sensory bottles and introducing magnifying glasses so that children can examine the different colors, shapes, and textures they have collected.

Once Ava identified children’s interests in natural materials, she was able to display items from nature throughout the learning environment and find ways for children to consistently interact with them. She and the children created artwork by sticking some of the nature items onto contact paper. They placed leaves, twigs, and pebbles into containers to create sensory bottles and maracas. Because these activities built on their interests, children were more likely to remain engaged in sustained interactions with them (NAEYC 2020). As a result, children began to acquire observation, classification, and language skills (Daly & Beloglovsky 2018).

Partnering with families to enhance the learning environment is another way to capitalize on children’s interests and to diversify the objects they encounter. Respecting and integrating different practices and materials that reflect children’s homes and communities create positive, bidirectional connections (Daly & Beloglovsky 2018). Educators can ask families to donate or lend everyday materials (pots, pans, utensils, textiles) to the learning setting. Ava, for example, gathered fabric, plastic bottles, empty food boxes, and cardboard packing materials from the families in her setting. By incorporating these familiar items from home, teachers help children make personal and emotional connections to them while gaining new knowledge and skills (Brown, Feger, & Mowry 2019). They also expose children to the similar and different ways families use everyday materials, giving them opportunities for enhanced exploration and discovery in their learning environments (Dauch et al. 2017). In turn, educators can showcase the benefits of following children’s interests and tapping everyday items as they share documentation with families.

Use Repurposed Materials

As Ava begins her journey, she starts small. She picks one area of her classroom to focus on and soon realizes she can provide meaningful learning experiences without making expensive purchases. She begins to see items in her home differently, and she talks with her administrator about materials in the program that she could transform for a different purpose.

While in her garage, Ava notices an old cabinet door that could be used as the base for a busy board. She finds muffin tins, pans, wooden bowls, and metal racks at a thrift store. She repurposes recycled plastic bottles, old technology (like a calculator), and everyday household items (like doorstops) from her home and program. Having these new yet inexpensive materials available in her classroom helps foster children’s curiosity and creativity. They also strengthen the connections children make between new and past experiences (Daly & Beloglovsky 2016).

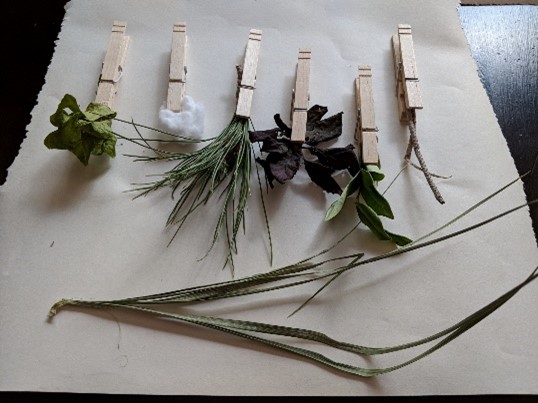

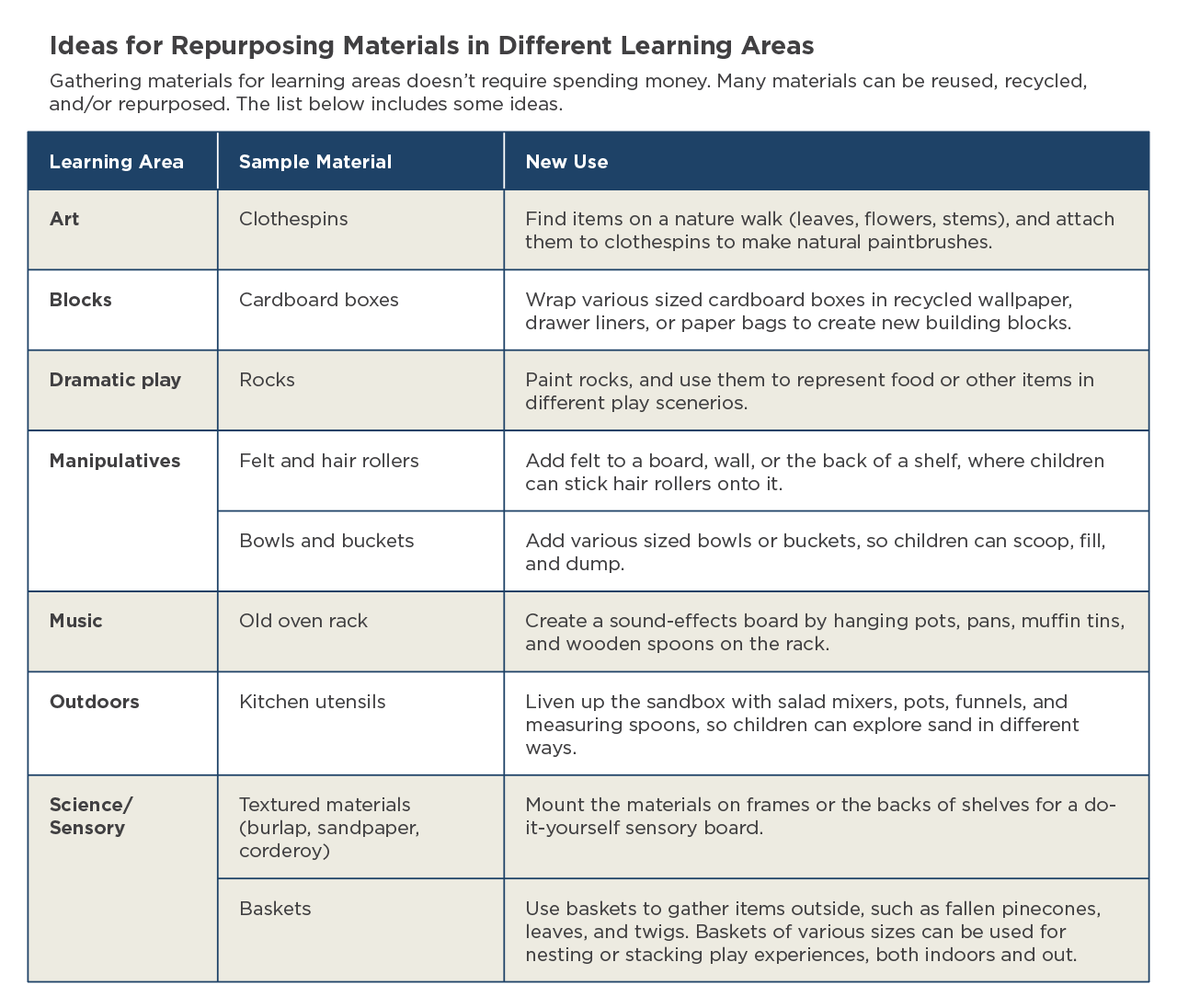

Teachers can enhance their learning environments by using items that are already available. According to Baumgart and Kroll (2018), young children often seek out upcycled, everyday objects and find new purposes and uses for them. They use these materials to symbolize and represent their imaginative ideas (Daly & Beloglovsky 2016). (See “Ideas for Repurposing Materials in Different Learning Areas” below.)

Families and community organizations can be good sources for upcycled materials. So can educators’ own programs: before throwing out toys with missing pieces or abandoning resources or furnishings that have been replaced, teachers can consider new uses by asking, “Can this item be used purposefully by the children in my setting?”

For example, when attached to walls or shelves, mismatched puzzle pieces with knobs can become hooks for dress-up clothes and other lightweight items. Old toys can be turned into parts of an activity or busy board, magnetic board, or felt board. Wooden salad utensils can become new and exciting digging tools for the sandbox or sensory table. Old lampshades can be added to the dramatic play or block area, where they might become tents or houses for toys and blocks.

Educators can also consider new ways to use the ceiling, walls, windows, and backs of shelving to intentionally capture children’s interests and draw them into stimulating discoveries (Deviney et al. 2010). Natural, textured materials and small everyday items that create sound and movement can be hung from the ceiling for children to observe. Sensory, music, and busy boards can be mounted on walls, so children can explore them while standing. Baking sheets, felt boards, plastic tubes, and piping materials can be mounted on the backs of shelves for children to explore. These repurposed materials create a learning space that allows children to use all of their senses from various perspectives. Children develop an awareness of their bodies’ capabilities, transition from unintentional to intentional actions, and grasp how objects relate to each other (Daly & Beloglovsky 2016).

Include Loose Parts

After reflective conversations and collaboration during coaching, Ava adds loose parts to different learning areas to intentionally support toddlers’ developing skills. In the dramatic play area, she provides tongs, metal bowls, wooden bowls, empty tin cans of various sizes, and large, colorful pompoms. She adds a basket of wooden shapes to the building area. In the manipulatives area, she includes wooden and metal paper towel holders with baskets of wooden rings, large fabric hair ties, and shower rings.

Recalling that one of the children in her class has a family member who works in construction, Ava asks if they could donate any materials. The following week, the family brings in wooden wire spools and cardboard tubes from used carpet rolls. Ava includes these items in her block area and watches how children begin using them to create ramps, bridges, places for cars to park, and tall towers. She listens to children talk about their plans to create a house for five animals—a lion, a dinosaur, a dog, a chicken, and a lobster. Ava is excited to see the children’s process of creative thinking, imagination, and problem solving as they discover new ways to use these loose parts.

Loose parts are natural, recycled, and upcycled materials that children can freely move, manipulate, control, and change within their play (Daly & Beloglovsky 2014). They are open-ended materials that promote children’s creative thinking, imagination, and problem-solving skills (Spencer et al. 2019), and they can be used alone or in combination with other materials in the learning environment (Houser et al. 2016). They invite children to investigate further, explore, and actively engage in learning. Indeed, children can use loose parts in many ways without specific directions; rather, they take the lead in the learning experience’s process and approach (Penn State Extension 2024). These multiple play possibilities provide a range of exploration opportunities, regardless of a child’s level of development and abilities (Gibson, Cornell, & Gill 2017). (For information on ways to encourage infants to explore with loose parts, see “Loose Parts in the Infant Setting” below.)

Loose Parts in the Infant Setting

Encouraging loose parts in infant environments can be beneficial for babies’ development. This kind of exploration allows them to engage their senses and fosters cognitive and physical growth. However, safety is of the greatest importance. Constant supervision during loose parts explorations is essential to ensure infants’ safe and active engagement (Daly & Beloglovsky 2016).

Because mouthing is expected as infants explore the materials in their environments, it is crucial to select materials that are appropriate in size and free from harmful substances on their coatings or finishes (Daly & Beloglovsky 2016). Teachers can use a choking tester or cardboard paper towel tube to test materials’ sizes to ensure they are safe.

Transparent, colorful scarves can ignite an infant’s visual curiosity. Items like jar lids, wooden or plastic cups, wooden or metal bowls, and boxes offer a diverse range of sensory experiences, from sound to texture to spatial awareness. Sensory bottles can appeal to and engage infants with their visual and auditory stimuli. Larger wooden rings, napkin holders, and similar objects promote fine motor skills through grasping and manipulation.

When choosing loose parts, it is essential to consider safety. Children younger than 3 explore with their senses—mainly their mouths. This puts them at higher risk for swallowing and choking (Barbre 2013). Because of this, educators should select loose parts that are large, sturdy, and cannot be pulled into smaller, hazardous pieces. Similar to selecting materials for infants, toddler educators should ensure that the coatings and/or finishes on these materials are free from harmful substances. They also should share these guidelines when asking families and outside groups for donations.

When choosing loose parts, it is essential to consider safety. Children younger than 3 explore with their senses—mainly their mouths. This puts them at higher risk for swallowing and choking (Barbre 2013). Because of this, educators should select loose parts that are large, sturdy, and cannot be pulled into smaller, hazardous pieces. Similar to selecting materials for infants, toddler educators should ensure that the coatings and/or finishes on these materials are free from harmful substances. They also should share these guidelines when asking families and outside groups for donations.

While loose parts can be rotated and moved to different learning areas, educators use their observations and documentation of children’s play to make intentional choices about where to place them (Smith-Gilman 2018). For example, if children are working on skills such as filling and dumping, teachers can add containers and objects of different weights and sizes. They can extend children’s play by engaging in conversations with them: What do the different objects sound like when they are dropped into containers? How do the containers differ in weight when they are filled and emptied?

Loose parts allow children to uniquely manipulate materials to demonstrate their understanding and build on their inquiries about the world around them (Gull et al. 2019). Indeed, loose parts play fosters scientific inquiry among children, offering them avenues for exploration, construction, design, invention, and problem solving. By using tangible materials, children dive into the realms of engineering, science, and mathematics. Additionally, engaging in insightful dialogues with educators enables them to expand their vocabulary and conceptualize fresh ideas (Daly & Beloglovsky 2018).

Conclusion

Thanks to the inspiration she receives from her coach, Ava is motivated to find new ways to create an inviting and exciting learning environment for the toddlers in her class. By implementing the three strategies, she transforms her learning space, which is now filled with children actively engaged in playful learning experiences as they learn new vocabulary and explore content area concepts.

By following children’s interests, using repurposed materials, and including loose parts, toddler teachers can create high-quality learning environments that increase children’s engagement and inquiry. Families can serve as partners in this journey. We hope Ava’s experience sparks inspiration and excitement for you to begin enhancing your own toddler learning environment.

Think About It

- What ideas in this article sparked your interest? How could you find ways to try them in your learning setting?

- Think about the materials you already have in your setting. How could you repurpose them?

- Take time to observe and reflect on how children engage with different types of materials. What keeps their attention and interest?

- In what ways do the materials reflect children’s home and community contexts? How can you expand on this?

- How could you use your unused space, such as walls or the backs of shelves, to engage children?

- Identify a learning area that children use less often. Think about what new items you could add to encourage engagement.

- Consider how you currently gather materials. Where do you go, and who do you contact? Are there new partners or resources that come to mind?

- How can you align the use of loose parts to foster development and learning across all domains?

Try It

- Set one goal and create a list of action steps to achieve it. Share your ideas and the goals you have for your learning environment with coworkers and families.

- Spend time observing how children interact with their environment. Notice which activities they are drawn to and what materials they seem most engaged with.

- Assess the strengths, interests, preferences, and needs of each learner. Based on observations and assessments, brainstorm ways to incorporate repurposed materials and loose parts to enhance each area.

- Create a list of items families and community partners can collect, and invite donations.

- Visit local hardware stores to collect samples or scraps, and share how you will use the materials in your setting.

- Visit thrift stores, discount stores, and garage sales for budget-friendly materials, always keeping safety in mind.

- Regularly evaluate the impact of the repurposed and loose parts on children’s engagement, learning, and development, and adjust and reevaluate as needed.

Rocking and Rolling is written by infant and toddler specialists and contributed by ZERO TO THREE, a nonprofit organization working to promote the health and development of infants and toddlers by translating research and knowledge into a range of practical tools and resources for use by the adults who influence the lives of young children.

Photographs: Header image © Getty Images; first image courtesy of Janelle Jamero; second image courtesy of Erin Skaggs

Copyright © 2024 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

Barbre, J. 2013. Activities for Responsive Caregiving: Infants, Toddlers, and Twos. St. Paul, MN: Redleaf Press.

Baumgart, N.A., & L.R. Kroll. 2018. STEAM Concepts for Infants and Toddlers. St. Paul, MN: Redleaf Press.

Brown, C.P., B.S. Feger, & B.N. Mowry. 2019. Rigorous DAP in the Early Years: From Theory to Practice. St. Paul, MN: Redleaf Press.

Daly, L., & M. Beloglovsky. 2014. Loose Parts: Inspiring Play in Young Children. St. Paul, MN: Redleaf Press.

Daly, L., & M. Beloglovsky. 2016. Loose Parts 2: Inspiring Play with Infants and Toddlers. St. Paul, MN: Redleaf Press.

Daly, L., & M. Beloglovsky. 2018. Loose Parts 3: Inspiring Culturally Sustainable Environments. St. Paul, MN: Redleaf Press.

Dauch, C., M. Imwalle, B. Ocasio, & A.E. Metz. 2017. “The Influence of the Number of Toys in the Environment on Toddlers’ Play.” Infant Behavior and Development 50: 78–87.

Deviney, J., S. Duncan, S. Harris, M.A. Rody, & L. Rosenberry. 2010. Inspiring Spaces for Young Children. Lewisville, NC: Gryphon House.

Gibson, J.L., M. Cornell, & T. Gill. 2017. “A Systematic Review of Research into the Impact of Loose Parts Play on Children’s Cognitive, Social and Emotional Development.” School Mental Health 9 (4): 295–309.

Gull, C., J. Bogunovich, S.L. Goldstein, & T. Rosengarten. 2019. “Definitions of Loose Parts in Early Childhood Outdoor Classrooms: A Scope Review.” The International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education 6 (3): 37–52.

Houser, N.E., L. Roach, M. Stone, J. Turner, & S. Kirk. 2016. “Let the Children Play: Scoping Review on the Implementation and Use of Loose Parts for Promoting Physical Activity Participation.” AIMS Public Health 3 (4): 781–99.

Lagiou, A., A. Asimaki, G. Koustourakis, & G. Nikolaou. 2021. “The Effect of School Space on Pedagogical Practices and Students’ Learning Outcomes: A Review of Scientific Sociological Literature.” Open Journal for Sociological Studies 5 (1): 31–42.

La Paro, K.M., & L. Gloeckler. 2016. “The Context of Child Care for Toddlers: The Expectable Environment.” Early Childhood Education Journal 44 (2): 147–53.

NAEYC. 2020. “Developmentally Appropriate Practice.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. NAEYC.org/resources/position-statements/dap/contents.

Penn State Extension. 2024. “Loose Parts: What Does This Mean?” Accessed March 6, 2024. extension.psu.edu/programs/betterkidcare/early-care/tip-pages/all/loose-parts-what-does-this-mean.

Rentzou, K. 2014. “The Quality of the Physical Environment in Private and Public Infant/Toddler and Preschool Greek Daycare Programmes.” Early Child Development and Care 184: (12): 1861–83.

Shrier, C. 2016. “The Value of Open-Ended Play.” Michigan State University Extension. Accessed May 25, 2021. canr.msu.edu/news/the_value_of_open_ended_play.

Smith-Gilman, S. 2018. “The Arts, Loose Parts and Conversations.” Journal of the Canadian Association for Curriculum Studies 16 (1): 90–103.

Spencer, R., N. Joshi, K. Branje, J.D. McIsaac, J. Cawley, et al. 2019. “Educator Perceptions on the Benefits and Challenges of Loose Parts Play in the Outdoor Environments of Childcare Centres.” AIMS Public Health 6 (4): 461–76.

Erin Skaggs, MEd, is an early childhood program coordinator for the Infant Toddler CDA Program at the University of Nevada, Reno Extension. Erin has worked as a preschool teacher at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas Preschool and as a developmental specialist with Nevada Early Intervention. She earned her MEd in early childhood special education from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Janelle Jamero is an early childhood education program coordinator for the Infant Toddler CDA Program at the University of Nevada, Reno Extension. Janelle has worked in the early childhood education field for over 20 years in several roles, including as an infant-toddler educator serving families in lower-income and homeless communities, a lead teacher, and an education coordinator.