What is a shadow? Denise Nelson and her class of preschoolers in Worcester, MA tried to answer that question over the course of a three-week exploration—both indoors and out.

Week One: Outdoor Shadows

The plan was to go outside and look for shadows, and my science training prompted me to think about using the Inquiry Cycle (Engage, Explore, Reflect) to organize our approach. We would engage and explore shadows both inside and outside, and then reflect on what we had learned from the two sets of experiences.

Step One: Engage

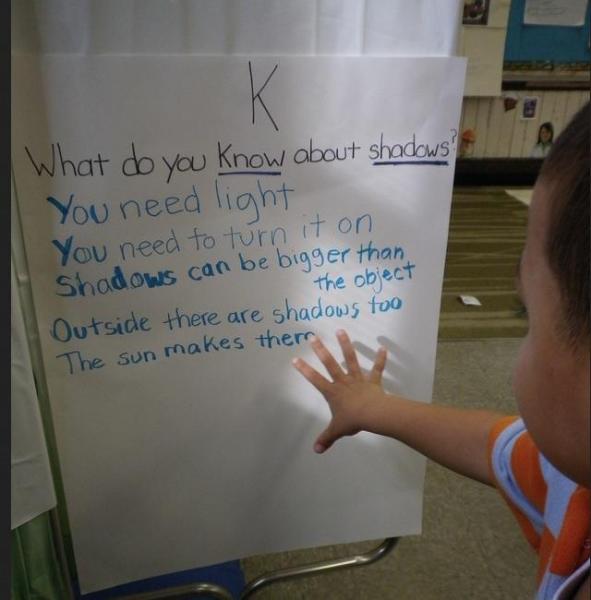

First I needed to find out what the children already knew about shadows. Getting them to talk about what they have experienced is a great way to engage them in further investigation. I engaged the children in small groups, using a KWL (K = What we already KNOW; W = what we WANT to know; L = What we LEARNED) chart and listing their answers to the first question, What do you Know about shadows?

My role at this point was to observe and listen carefully.

This activity helped me understand that the children did have some prior knowledge about shadows. One child saying, “You need to turn it on” was thinking about a flashlight. Some of the children were aware of outdoor shadows.

We were ready for the next step in the Inquiry Cycle: Exploring!

Step Two: Explore

Throughout the first week, we went outside looking for shadows. I always brought my phone along—taking pictures is an important documentation tool. Children would call out, “I see my shadow!” “There it is!” “Look at my shadow!” I watched as they experimented with positioning themselves in different ways in order to observe what happened to their shadows. I asked questions to encourage them to focus: “What else has a shadow?” “Does the fence have a shadow? The flagpole?” Iliana noticed that when she jumped, her shadow jumped, too. She liked the way her shadow-hair bounced around.

She noticed her shadow was “bent.”

One day, we had an overcast sky. “Uh-oh,” I thought. “I’m going to have to tell the children there will be no shadows today.” Then I caught myself: Wait a minute! One of the key aspects of teaching science is knowing when to stay quiet; allowing children to make discoveries is central to the engagement and learning process. I allowed the children to go outside, chalk in hand, to do some shadow tracing. They gathered in an area where they had seen shadows the day before. I asked, “What’s going on?” One child complained, “Our shadows are gone! We can’t see any!” I rephrased their concern: “You saw your shadows here yesterday. Today you cannot see them. I wonder why?” Many children had their eyes focused on the pavement or on the fence fabric. A few looked toward the school building and others up at the sky. After a pause, one child called out, “The sun! The sun! Shadows are gone because the sun’s not out!”

I never tire of their “A-ha!” moments.

Week Two: Indoor Shadows

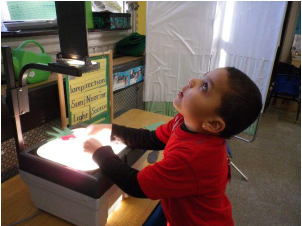

We continued our open-ended exploration of shadows inside. There are a number of resources teachers can use to learn more about deepening children’s scientific inquiry. Look for resources that encourage children to discover answers for themselves through scientific inquiry. I used a unit from the PEEP Science Curriculum—a set of six free STEM units from the public television preschool series, “PEEP and the Big Wide World.” I followed the guidelines for using an overhead projector as a learning center and let children freely explore objects and their shadows.

Otherwise, I let the children freely explore objects and their shadows.

They began experimenting with the projector, using their hands to make shadows appear on the wall. They also made use of paper shapes. To advance their inquiry, I asked questions like, “What do you notice?” “How did you do that?” “Why is it blurry?” The children continued experimenting by moving objects around. Some spent a great deal of time manipulating objects and observing their results. They found that turning an object changed the shape of its shadow, and they detected differences in clarity when shapes were moved closer to and further away from the light.

Later in the week, we watched an episode of Night Light on our computer. In this 9-minute animated episode, Peep and friends find a flashlight and have fun making a variety of shadows with their bodies. Pairs of children viewed it throughout the day. There was a tremendous amount of laughter and discussion going on. One of the comments included, “It’s just like us. They are playing with shadows just like us!” By far, the children’s favorite clip was when the bird characters, Peep and Quack, use a pocket watch to divert the light and change the shape of their shadows.

Later in the week, we watched an episode of Night Light on our computer. In this 9-minute animated episode, Peep and friends find a flashlight and have fun making a variety of shadows with their bodies. Pairs of children viewed it throughout the day. There was a tremendous amount of laughter and discussion going on. One of the comments included, “It’s just like us. They are playing with shadows just like us!” By far, the children’s favorite clip was when the bird characters, Peep and Quack, use a pocket watch to divert the light and change the shape of their shadows.

That scene from the clip also provided some new inspiration.

One boy made a fantastic discovery: He found he could adjust the mirror on the projector and send shadows to the ceiling! A crowd gathered to find out how he had done it. I allowed him to demonstrate and asked him to explain. “Tip it up, like this,” he said. “It makes the light shine up this way and up to the ceiling.”

I used this opportunity to reinforce one of our science vocabulary words: direction. “So you’re saying that when you shine the light from a different direction, the shadows appear in another place?” “Yes,” he agreed. “The mirror has to be straight up.” The children were doing more than just observing; they were trying to make sense of their observations and connect the cause and effect relationship. It would soon be time to help the children reflect on their experiences to date.

Week Three: More Focused Exploration

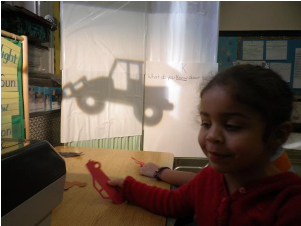

The children began to show more advanced inquiry skills in the second (indoor) week, exploring the relationship between actions and outcomes. Those inquiry skills continued to thrive in our third week, as we tried the “shadow theater” activity from the PEEP Science Curriculum — using shadows to create a variety of characters and tell a story. The set-up involves projecting a light onto a hanging white sheet and having children use their bodies to make shadow “characters”. I involved three to five children at a time.

Students looked at their shadows on a big white sheet. They tried to identify friends from the other side of the sheet. Some began coming up with reasonable explanations for changes they noticed in the shadows:. “My hand looks so big because it is next to the light.” I also heard predictions: “It will get smaller if I put it next to the sheet.” They tested their predictions and concluded, “See! I told you! Next to the light makes giant hands!”

Step Three: Reflect

As we’d been working with indoor shadows for a week, it seemed time to reflect together on our growing list of observations. I worked with three to four children at a time, tailoring my questions to the developmental level of each group. When working with 3-year-olds, the conversation revolved around, “What makes shadows?” and “What happens when I shut off the light?” If 3-year-olds can answer that the light (or sun) causes shadows, or can indicate that a person or object is also needed, I recognize they’re constructing important STEM knowledge. Some older children were able to inform me of all the steps needed to explore shadows: “You need a sunny day, or a big light,” “You have to use your hands or things like puppets. And a thing to shine on. Maybe a blanket or the ground.” Using photos I had taken, they recalled other information they wanted to share: “When you move, the shadow moves. When you jump, your shadow jumps. If you put something close to the light, the shadow gets bigger.”

Equipped with photographic evidence across three weeks of exploration, we met to discuss our results. Everyone agreed that the sun made the best shadows. Some comments I heard: “The sun is much better than a flashlight—it makes bigger shadows.” “The shadows are darker from the sun,” “Outside shadows are better because they move around a lot.”

I was curious about whether the children had developed theories about what they experienced. I asked, “What is it about the sun that makes those outdoor shadows so good?” The answers rushed forth: “It’s bigger, the sun—it’s so much bigger than the flashlight,” “It’s high up in the sky so it can shine on a lot at once,” “You don’t have to hold it like a flashlight.”

The theories children contribute put forward don’t have to be scientifically sound. What’s important is helping children think about their experiences and challenging them to construct explanations based on their existing knowledge. It will take many experiences for children to develop conceptual understanding of a topic of study, but at least we’re now familiar with the inquiry cycle.

What Children Learned

Our three week shadow project resulted in many different learning outcomes for the children:

Science

- Students learn that a shadow is made when an object blocks the light.

- Children make shadows with their bodies and other objects.

- Children observe that a shadow can show an object’s shape, but it can’t show colors or details (like a smile or a frown).

- Students change a shadow’s shape by moving/turning their body or the object, or by moving the light source.

- Children combine shadows to make different shadow shapes.

- Students discover that each light source directed at an object will create a shadow.

- Indoors, chldren can change the size of a shadow by moving their body or the object closer to/ farther from the light.

- Outdoors, children see that a shadow’s shape, size, and position change over the course of the day as the sun’s position changes.

Language and Literacy

- Children become familiar with vocabulary words such as shadow, light, bigger, smaller, closer, and farther.

- Children see their words written on charts. They listen and “read” along as words are read back to them.

- Children listen to read-aloud books about shadows and explore books independently.

- Children practice emergent writing skills by recording their shadow observations through drawing, tracing, and “writing.”

Early Math

- Children describe, measure, record, and compare the shapes and sizes of shadows.

Thanks to Gay Mohrbacher, Senior Project Manager at WGBH Boston, who helped to develop and edit this essay with NAEYC staff.

Denise Nelson, MEd, is an education coach at the Worcester Child Development Head Start Program and a professor of education at Worcester State University. Denise has been a member of the inquiry group for two years. [email protected]