A Scribble Is Never Just a Scribble: Art, Story, and Process

You are here

Editors’ Note: NAEYC recently published a new edition of its essential text, Developmentally Appropriate Practice in Early Childhood Programs Serving Children from Birth Through Age 8, Fourth Edition. To accompany and extend the rich and detailed content in the book, there are a variety of DAP resources in the book’s appendices and online. One resource is called “DAP in Action: Snapshots and Reflections.” Early childhood educators from a variety of settings submitted vignettes, or snapshots of practice, which show connections to key DAP concepts as well as a self-reflection on that moment in time.

The following DAP snapshot and reflection touches on how one teacher responded to children’s marks on paper, encouraging creativity and integrated learning, particularly around drawing, writing, and storytelling. We encourage you to consider how DAP comes alive in your work with young children. Visit NAEYC.org/DAP-vignette to learn more and to share your snapshots and reflections on DAP.

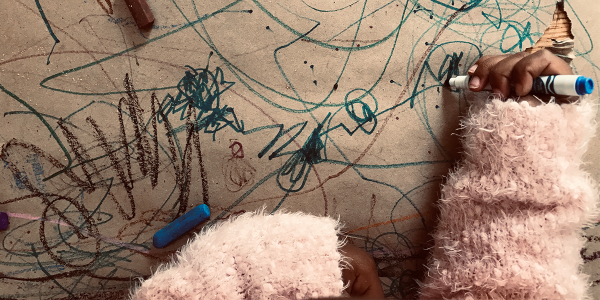

At the beginning of the year, the 2- and 3-year-olds in our class often asked us, the teachers, to draw particular things: family members, dogs, and other people and animals they encountered regularly. The children enjoyed the work we teachers produced but remained convinced that any work they themselves did was subpar because it did not match their teachers’ style. Typically, their drawings were done hastily, left just as quickly, and forgotten.

We wanted the children to see the value of their work and be proud of what they created, so we stopped drawing for them. Instead, we focused on encouraging them in the work they did. Here’s how we made the shift and got the children excited and talking about what they drew.

A Process of Inquiry

“Tell me about what you have here” is a statement that invites a response. It does not demand a particular right answer, offer a value judgment, or seek to change the process or product a child has made or is working on. What this statement does do is ask a child to bring the inquirer a little deeper into their thinking; as teachers, this is one of the most important and fulfilling features of the work we do each day.

Through informative statements and invitations like this one, we encouraged the children in the work they did. For example, we might pick up a scribble left behind on the table and say things like “Wow! Tell me about this. It looks like you worked hard on it,” “I see a lot of lines going really far across the page. It’s all in red. Tell me more,” or “Whoa. That was all done really fast (slow). You seemed focused on it.” These instances of scaffolding offer children opportunities to begin deconstructing their own processes of thinking and creating and reinforce the value of their processes and products.

With time, scribbles that were once abandoned began to have value for the children. The children held on to them and even sought out their teachers to share their work. The pieces of work assumed stories and identities that demanded to be not only valued but written and shared. Along with the children’s names, we also began adding these stories about the art to the art itself.

The Vignettes

In the following vignettes, I offer two examples of the ways we incorporated process and assessment through this work. In each, you will see how assessment was integrated into a child’s ongoing and unfolding work. By doing so, I was able to see the children’s level of performance in contexts that reflected their unique ability and skill and in which they were intrinsically motivated, focused, and engaged.

“A Monster, I’m Not Afraid of Anything at All”

Three-year-old Jiro runs over to me, clutching in his right hand a white half sheet with loopy lines of crayon etched across the front. “Ron! Ron! I made this. It’s called ‘A Monster, I’m Not Afraid of Anything at All.’ I did it.”

“Whoa, that is a lot of color!” I exclaim. “Look at the work you did—such hard work.”

“Yeah,” he replies. “Write it down.”

After finding a pen, I write down Jiro’s words, verbatim, on the work he created. I then ask him if he has a story to accompany it. He is ready for my question and excitedly dictates a story about a bear who loses his mommy and then finds her in a cave.

When Jiro is finished telling his story, he goes off to play. For today, at least, he has finished his work. His pride is evident, and seeing it, I know that one of the most important goals has already been achieved.

The Name

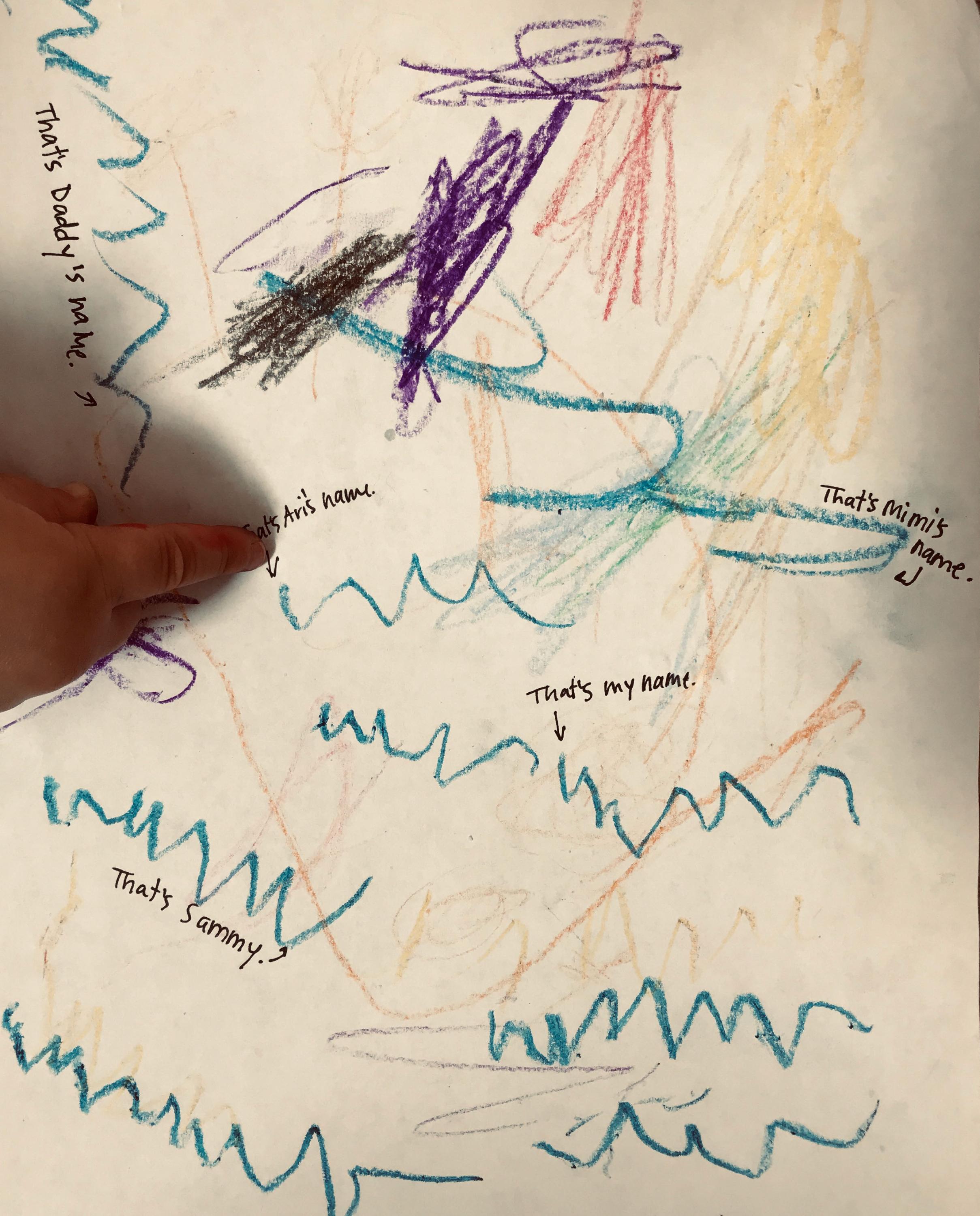

Another day, I am on the block rug when Raven, who is 2 years old, comes up to me with her work. I take a brief moment to revel in the comfort that this practice of close sharing has fostered in our classroom.

“Tell me about this,” I say intently as she kneels next to me.

Her page is alive with colorful lines that dart across the paper at all angles. Fine motor control? Check. An appreciation of thorough composition? Check. There is a circular figure in orange in the background; three intense strokes of red, purple, and black race across the top. A squiggle of yellow is to the right. There is a series of blue lines that move up and down across the whole page, and I quietly wonder what they are. Waves? Birds? Snakes?

“It’s my name,” Raven tells me, her voice gleeful.

“Your name? Whoa!” I point to another of the blue lines. “And what about that?”

“That’s my mommy’s name,” she informs me.

As we talk about many of the lines, I learn that she has written the names of all of the members of her family, including her grandparents. By asking specific questions about her work, I am able to learn more about Raven’s interests in literacy, her understanding of text and pictures, and her ideas about the information those elements convey. I am also showing her that I value her work and the thought she puts behind it.

How different our conversation might have been had I said only something like “Nice work” or “It’s so beautiful!”

Self-Reflection

Over the following days and weeks, the children’s interest in giving context to their art continued to deepen. One child was inspired to dictate a series of stories over multiple days; each story was illustrated with a similar array of swirling lines across a formerly stark white page. We teachers began putting the children’s work on the walls—but, as I always insisted, never without at least a few words to accompany them. By adding children’s words to their artwork in the form of titles, descriptions, and stories, we extended the process of learning. It is a critical part of integrated learning to show children that the work they do in art relates to the work they do on the reading rug—and that all their work has an overarching connection to themes and experiences that make up the content of their thinking.

A scribble is never just a scribble, and we should always be open to the true depth and beauty of a child’s creative mind. Don’t be afraid to say “Tell me about what you have here.” You might just be surprised at what you find out.

Connections to Developmentally Appropriate Practice

In reflecting on these experiences integrating children’s art, storytelling, and narrative insights into their work, the connections to the 2020 position statement on developmentally appropriate practice become clear.

For example, educators are urged to plan the environment, schedule, and activities in ways that promote each child’s development and learning (guideline 4, section D). In our classroom, this meant thinking about and discussing the fact that we teachers were spending significant time drawing for the children. The situation invited us to make many adjustments in how we responded to the children, set up the classroom, and thought about children’s work. These changes in our practice, including introducing a process of inquiry, helped us as teachers to better understand the children’s thinking and helped the children value their own work more highly.

The position statement also emphasizes the necessity of collecting a child’s work samples and considering their performance in authentic situations to construct a genuine understanding of that child (guideline 3, section D). Raven’s squiggles and lines were genuine points of pride for her. Discussion of these marks was embedded in our authentic conversation, and her enthusiasm, intention, and skill gave me insight into multiple levels of Raven’s relationship with mark making. Through the languages of story, mark making, and art, I see children demonstrating their strengths and competencies in different ways. I observe how one child is developing an emergent sense of narrative that he connects to his own life and how another is developing fine motor persistence while also honing her appreciation for the differences between letter forms and the forms used to convey artistic information. Jiro the storyteller and Raven the scribe are each right on track exactly where they are, and they should be celebrated for it.

The position statement also emphasizes the necessity of collecting a child’s work samples and considering their performance in authentic situations to construct a genuine understanding of that child (guideline 3, section D). Raven’s squiggles and lines were genuine points of pride for her. Discussion of these marks was embedded in our authentic conversation, and her enthusiasm, intention, and skill gave me insight into multiple levels of Raven’s relationship with mark making. Through the languages of story, mark making, and art, I see children demonstrating their strengths and competencies in different ways. I observe how one child is developing an emergent sense of narrative that he connects to his own life and how another is developing fine motor persistence while also honing her appreciation for the differences between letter forms and the forms used to convey artistic information. Jiro the storyteller and Raven the scribe are each right on track exactly where they are, and they should be celebrated for it.

In observing the children’s creations, it was evident that while there were some similarities in their interest in and ability to draw, there were also variations in the themes they chose to focus on and their techniques. These variations contributed to our understanding of each child’s creative and intellectual processes. Some children were making purely experimental marks on paper, while others were creating marks with the intention of representing specific information. The children’s diverse range of interests, fine motor skills, experiences, and social contexts all contributed to them experiencing these activities in their own way (principle 4).

Finally, the position statement emphasizes the importance of an integrated approach to learning (principle 7). Learning and development in any given domain is not an isolated occurrence, and by considering multiple subject areas together, concepts can be made more meaningful and engaging for children. There is an inherent artistry in making literacy-related marks as well as a relatedness between narrative understanding and oral storytelling. Educators’ awareness of this interconnectedness encourages children to build on their understanding in each domain.

Photographs: courtesy of the author

Copyright © 2023 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See permissions and reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

This article supports the following NAEYC Early Learning Programs standards and topics

This article supports the following NAEYC Early Learning Programs standards and topics

Standard 2: Curriculum

2B: Social and Emotional Development

2D: Language Development

2E: Early Literacy

Ron Grady, MSEd, is an early educator, author, and illustrator whose written and artistic work focuses on children’s social worlds. He is a third-year doctoral student studying education at Harvard.