From Feeling Like an Imposter to Knowing I Am Indispensable: Embracing My Identity as an Educator

You are here

I am a first-generation US citizen. Within me lie Mayan and Aztec roots, reflecting my mother’s Guatemalan and my father’s Mexican heritage. I grew up in Arizona, a state with a large Latino/a population. Yet surprisingly, I spent most of my school years in predominantly White schools staffed overwhelmingly with White teachers. Though I am fluent in English, I have always considered español (Spanish) to be my first language.

My family was an intergenerational household that included my Spanish-speaking maternal grandmother, whom I adored. I always saw my Spanish as a skill, and I would translate for my grandmother, teachers, and friends at school. My parents were hard workers, but my family lived paycheck to paycheck for much of my life. I started helping to contribute to the household around the age of 7 when I would help my mother wash and iron other people’s clothing or advertise to all I met that my mom was a cosmetologist and was great at cutting hair. I even helped my grandma sell Indigenous Guatemalan clothing to neighbors in our apartment complex.

Helping my family financially in the informal economic sector was natural for me, and even as a young child, I knew what an important role I had. At the same time, I knew my responsibilities were different from those of my friends at school. Interestingly, this motivated me to achieve success. I was lucky to have two elementary school teachers who believed all students could be successful, and these teachers became my role models. First, I was placed in Mrs. Schick’s class, who taught in a pilot program where children looped with the same teacher for three years from first to third grade. I observed that Mrs. Schick was a no-nonsense teacher who set high expectations and had deep trust in us as children.

Then, at age 9, I met my fourth-grade teacher, Mrs. David, a teacher all the children loved. I remember the anticipation we all felt as we waited to see if we would be placed in her class and the joy I felt when I found I was one of the lucky ones.

We loved Mrs. David because Mrs. David loved her students and went out of her way to include us in her life. She included students in classroom decisions and always found time to check in with us and our families. She even exposed us to experiences outside of the classroom walls. I remember when she invited me and three others to the historic Orpheum Theatre in Phoenix to see her daughter perform in a play. To this day, I can remember how special it felt to be invited to attend. Mrs. David was also the first teacher I ever remember mentioning a place called college. I didn’t know all the details about college, but I knew it was something I had to reach to achieve the success I dreamed of.

The Teach For America Experience

It was not an easy journey to attend college, especially because no one in my family had attended. There was so much I did not fully understand, and many times I felt like an imposter. After nine very unconventional years, three changes of my major, and almost $60,000 of debt, I graduated with my Bachelor of Arts in political science. I had every intention of pursuing a career in social justice, but finding a well-compensated job opportunity was proving to be hard, even with a college degree. When I attended a university career fair, education found me through Teach For America. I did not have a background in education but Teach For America aligned with many of my social justice ideals. I believed in their vision statement: “One day, all children in this nation will have the opportunity to attain an excellent education.” I dreamed of working abroad, but as I pondered the decision to apply, I realized that I did not have to move abroad to achieve my goals. I remembered Mrs. David and all the amazing teachers that influenced me over the years. I decided that I was willing to take a chance on education as a profession. In 2018, I was accepted as a Teach For America corps member and placed in a language immersion charter school in the greater Cleveland area.

Though I was thrilled to have been placed in a language immersion school where I could teach in español, the six-week student teaching experience provided by Teach For America made me feel like an imposter again. My first years of teaching were overwhelming in so many ways, but I also realized that I loved teaching kindergarten. I was working at a site with limited resources and high demands: the pressure to perform, a low salary, a lack of preparation time, and the constant need to buy supplies out of my own pocket all combined with the stresses of the pandemic. These realities caused me to look elsewhere for opportunities where I could develop as a professional. I found that opportunity in a university laboratory school.

Engaging with Children About My Identity

The laboratory school where I teach kindergarten in the midwestern US is an authorized International Baccalaureate Primary Years Program World School and is inspired by Reggio Emilia. The center serves 150 children from 18 months through age 5 from various cultural, socioeconomic, and linguistic backgrounds in mixed-age classrooms. Most of the children are White. Approximately 25 percent of the children are considered international, and several different languages can be heard throughout the school. Ninety percent of the families include university faculty, staff, or graduate students.

I loved the way the other teachers and staff talked about children and interacted with the children at the lab school. With three years of teaching under my belt, I did not expect to feel like an imposter. Yet, once again, I did. It had been easy to be myself in a school with a bilingual program that embraced my culture and that served a predominantly Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) community. Now in the lab school, I was the only staff member of color and the only one who spoke another language in addition to English. While there was some cultural diversity among the families and children, I struggled with how and if I should share my identity in the classroom, especially as I was trying so hard to follow the children’s lead. At the same time, the lab school provided preparation time, a high level of professional development, and a real focus on how the children were learning and developing, all of which allowed me to learn so much as a professional. Yet I was losing my identity. The more I tried to assimilate, the less joyful I became as a teacher. I was hiding who I was from my colleagues and the children in my class and missed so many moments to connect because of my uncertainty.

At the height of my uncertainty, the following conversations took place:

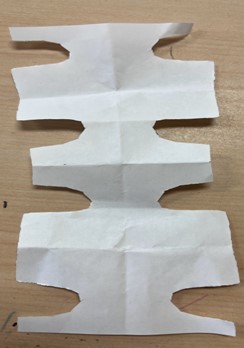

Alexis: Mrs. Knapp, I made something for you.

It was a white paper cutout. I immediately thought of the papel picado banners used in Mexico during Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead). But instead of saying that, I simply said thank you and hung it on my door.

One week later, the following was shared by Bret during our morning meeting.

Bret: I am actually feeling sad today because my great-grandma is going to die soon.

Alexis: How do you know?

Bret: Because she has been very sick, and the doctors told my family.

Two weeks later, Bret shared the following update.

Bret: I’m still feeling sad about my great-grandma because she is still sick, and I don’t want her to die.

Alexis: My cat died.

Elena: My dad’s brother died when he was a baby.

Leo: Isn’t it inappropriate for kids to talk about dying?

Me: Why do you think it is inappropriate for children to talk about dying?

Leo: I don’t know. I think I heard someone say that one time.

My stomach sank. My choice was to continue ignoring Bret’s obvious concern and his classmates’ experiences or possibly risk backlash for addressing a taboo topic. As the authors of Anti-Bias Education for Young Children and Ourselves note, “If adults go silent about things that children are seeing and trying to understand, children absorb the emotional message that the subject is dangerous and should not be talked about. This leaves children with an undercurrent of anxiety and unease, which are the earliest lessons about bias and fear” (Derman-Sparks & Edwards, with Goins 2020, 52). I knew I could not go silent during this morning meeting.

I decided to talk about Día de los Muertos by referring to the cutout that I had received from Alexis. Our conversation continued.

Me: Alexis made this for me, and it reminds me of a tradition that is celebrated in Mexico and other countries. Does it remind you of anything?

Alexis: It looks sort of like a skeleton.

Elena: I think it looks like a banner.

Oliver: It looks like a decoration.

Bret: I know what you are talking about, Mrs. Knapp. It’s Day of the Dead!

Oliver: I’ve heard of that. It’s in my movie Coco.

Me: Yes! En español we say Día de los Muertos. Día de los Muertos is a very special celebration for me because it is a day when I can remember all the people I love and have lost. This is a picture of my dad. He died in 2019.

Bret: He looks much younger than my grandma. Did you cry when your dad died?

Me: I did. A lot. It was a very sad time for me, but every year during the Day of the Dead, I remember all of the good memories we had together, and I make his favorite food, frijoles (beans) and tortillas.

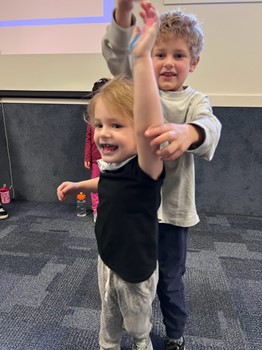

Bret seemed at ease during this conversation, and the children had many questions about this tradition. I shared pictures of altars, marigolds, and the types of foods people eat during Día de los Muertos. We learned to dance salsa and greet each other in español. Outdoors, the children began collecting yellow dandelions and asked to create a class altar. These conversations went on for weeks and eventually led to the children planning a Día de los Muertos celebration for our school community. They planned activities, learned to make authentic Mexican food, and sent out invitations to each classroom. Everyone from the toddler classrooms to our school director came to experience and learn about Día de los Muertos.

I was amazed at the interest children showed in Día de los Muertos. The children took any opportunity to learn more Spanish. Our associate teacher introduced bilingual books during read alouds. The children were intrigued by these books and asked if our associate teacher could read the story in English and if I could read the story in Spanish so they could hear if any words sounded similar. We learned to count to 20 in español. Conversations about Día de los Muertos became an almost daily occurrence, which led to inviting families to share pictures and stories of their loved ones, pets, or favorite authors or musicians who had passed away. I was nervous about how families would react to this celebration, but even the adult family members seemed to enjoy learning about Día de los Muertos. The following is an excerpt from a parent's email:

I mentioned salsa tonight (the kind you eat), and Henry began to tell me about salsa dancing. He was quite proud to show me and take me through some spins and dips. It definitely wasn’t salsa as most people would know it, but it was a very sweet moment. Apparently, Elena and Oliver are the best salsa dancers in the class, according to Henry.

Integrating My Identity into the Classroom Context

It is sad to think that this experience may have remained a decoration on my door. Feelings of being an imposter, along with the delicately woven systems of oppression that exist in schools, often stop educators from sharing their true identities. This can be especially true for educators who are the first in their families to pursue higher education (Breeze 2018). The truth is that I cannot leave my identity at the door, nor should any educator do so. I have never had a Latino/a teacher and continue to notice the lack of other Latino/a teachers in the field. Yet I know that my cultural background and all the social identities I embody help me be aware of the many strengths and struggles of the children and families I serve. I am not an imposter; rather, I am indispensable.

References

Breeze, M. 2018. “Imposter Syndrome as a Public Feeling.” In Feeling Academic in the Neoliberal University: Feminist Flights, Fights and Failures, eds. Y. Taylor and K. Lahad, 191–219. London: Palgrave Macmillan Cham.

Derman-Sparks, L., & J.O. Edwards. With C.M. Goins. 2020. Anti-Bias Education for Young Children and Ourselves, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Sara Knapp is a kindergarten teacher at Kent State University Child Development Center in Kent, Ohio, where, along with teaching, she mentors preservice teachers and participates in early childhood research. Sara was selected to be the 2022 Groundwork Ohio fellow and is featured in the Groundwork Ohio blog. [email protected]