Engaging Families of Multilingual Learners: Using Families’ Stories to Link Classroom Content with Children’s Funds of Knowledge

You are here

Ms. Bernice is exploring a transportation unit with her mixed-age preschool class. All of the children are multilingual learners, with Spanish as their home language. While Ms. Bernice provides many small-group lessons and read alouds related to transportation, she wants to visibly incorporate families’ experiences. Toward this end, she asks families to audio or video record themselves narrating a short story (in Spanish) about a traveling experience they had with their children and to share a poster or collection of photos related to the story.

The responses, which come in via the class communication app, are swift and enthusiastic. As families send in their stories, Ms. Bernice creates QR codes for their recordings and videos, which she attaches to the collages and posters the families created. She hangs these at eye level in the library area so that children can use the class tablet to scan the QR codes and share the stories with each other. The children enjoy having their families featured in the classroom virtually, and they revisit the artifacts several times a day.

Ms. Bernice watches the videos and listens to the recordings alongside the children, asking them follow-up questions and sharing stories about her own family’s travels. Lupe, a 4-year-old who is reluctant to speak in group settings, holds up the picture collage she made with her mother. She tells Ms. Bernice, “Buelo driving the car, and I was in the car, and I went to the mountain, and I went to the bear, and I went to the unicorns, and Buelo bought me a bicycle, and the end.” As Ms. Bernice asks Lupe more about her trip, they continue to chat about her mode of transportation (a car) and how it differs from the buses, planes, and boats featured in other children’s stories.

Ms. Bernice (the second author) teaches 15 preschoolers in a publicly funded program in New Jersey. Through participation in a National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) project aimed at boosting the number of Latino/a preschool teachers in the state, she worked with Alexandra (an assistant research professor and the first author) to investigate ways to increase family engagement and reflect their funds of knowledge in her setting. This is a key part of developmentally appropriate practice (DAP) and advancing equity: Educators understand that families are the primary context for children’s development and learning, and they look for ways to incorporate their funds of knowledge into their curricula, teaching practices, and learning environments (NAEYC 2019). They also use home languages to enhance children’s communication, comprehension, self-expression, and learning (NAEYC 2020).

With Alexandra’s support, Ms. Bernice began to use Quick Response (QR) codes and tablets to bring family narratives—keyed to specific units of study—into her classroom. In this article, we outline the benefits of using technology as a tool to create equitable learning environments that integrate and celebrate families’ strengths, interests, and funds of knowledge. We also offer guidance for educators who would like to enact these practices in their own settings.

Using Technology as a Tool to Learn About and Link to Families

High-quality educational spaces for multilingual learners must include intentional supports and responsive environments (Castro, Espinosa, & Páez 2011; NASEM 2017)—not only for language development, but also for fostering equitable and engaging relationships (Paris & Alim 2017). Children must feel accepted, comfortable, and safe in order to take the necessary risks that come with learning a new language. This is particularly true when children are in the developmental stages of language learning (Tabors 2008).

Toward this end, teachers must have a dynamic understanding of children’s families, cultures, and languages (NAEYC 2022). This provides opportunities for them to create connected educational experiences that engage children in interactions and conversations that build vocabulary and other academic skills in meaningful ways (Neuman, Kaefer, & Pinkham 2014).

Through their funds of knowledge theory and methods, Moll and colleagues posit that understanding families—through their routines and resources, relationships and social networks, and their assets—provides opportunities to dispel deficit assumptions and instead view families through a strengths-based lens (1992). Much of Moll’s research focuses on the use of interviews and observations in homes to understand everyday interactions and to garner confianza, or the cultural value of generosity, intimacy, and reciprocity, between educators and families. In practice, some settings include home visits, intake forms, and/or home language surveys as part of their early learning programs. However, it is important to think about how we as educators learn about families and develop reciprocal partnerships with them (Iruka 2019). We need to consider how we can use an array of approaches and tools to better understand children’s funds of knowledge to create high-quality learning experiences and to nurture strong and confident learners.

Technology is a helpful tool for learning about families and making home-to-school connections (Hall & Bierman 2015). Given our experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic and the ways in which technology is so present in our lives, it seems a missed opportunity not to tap commonly used devices (such as cell phones) to creatively and responsively seek and incorporate families’ funds of knowledge. Moreover, creating social and cultural links to everyday lessons is key to building on interests and background knowledge and to achieving language goals for multilingual learners (Méndez et al. 2015).

We argue that using QR codes and audio and video recordings are opportunities to integrate technology in positive, meaningful ways. This must be done carefully: “Technology should not be used for activities that are not educationally sound, not developmentally appropriate, or not effective” (NAEYC & Fred Rogers Center 2012, 4). In our work, technology is used to intentionally connect family stories to a unit of classroom study for “effective learning and development” (5). For example, Ms. Bernice’s use of technology enabled her to get to know families asynchronously and to incorporate their cultures, languages, and experiences into an ongoing topic of study (transportation). She was able to share this topic with families, bring in relevant family stories about it, provide an opportunity for children to see their families reflected in the learning space, and build content knowledge by relating new ideas to children’s actual lives. These are key strategies for working with multilingual learners as well as engaging families in reciprocal ways.

Little research has been done on technology’s use in connecting with families to deepen concept development for multilingual learners. However, some preliminary research on preschool children’s use of QR codes to create interactive learning has shown benefits: One study showed that using interactive QR codes to build math concepts increased the performance of a small sample of children (Mowafi & Abumuhfouz 2021). Other studies have shown that the practice spurs children’s independent and supportive learning (Thorne 2016; Hung 2018). Our work examines a specific, new avenue: using QR codes as a link between multilingual learners’ home and school contexts as an example of intentional practice that other educators can consider in relation to their own settings and practices in various ways (see “What Are QR Codes?” below).

What Are QR Codes?

Quick Response (QR) codes are a mechanism to provide access to digital actions—such as linking to a website, video, or photo—without requiring users to download an additional app. They also help ensure that users go to an intended location. They have become popular in settings such as zoos, museums, and parks as a way to provide videos, pictures, and other information to enhance content or exhibits.

QR codes are easily produced by an adult on smart phones, tablets, or computers through free platforms, such as Google QR Code Generator. These platforms generate QR codes from data like URLs or other text-like contact information.

Piloting an Idea: Connecting Children, Families, and Classroom Content Through Technology

In order to make responsive instructional decisions, it is vital for educators to be aware of the specific cultural and linguistic backgrounds and lived experiences of each and every child in their settings (García & Frede 2010; NAEYC 2020). This is especially important among Latino/a children: despite sharing a common language, other cultural traits (immigration status, histories, economic standings, exposure to English, home literacy practices, families’ educational backgrounds) vary significantly (Park, Zong, & Batalova 2018). Without all of this information, it is difficult for teachers to make intentional decisions, including about their learning environments, instructional practices, and supports, which matter for multilingual learners (NASEM 2017).

When teachers speak the same language as children and families, gaining this knowledge is more easily accomplished. However, the reality is that a linguistic and cultural match between teachers and multilingual children is not the norm (Williams et al. 2023). This mismatch creates a challenge as even teachers who identify as Spanish speaking can feel underprepared (Ryan, Ackerman, & Song 2005; Ray, Bowman, & Robbins 2006; Choi et al. 2021).

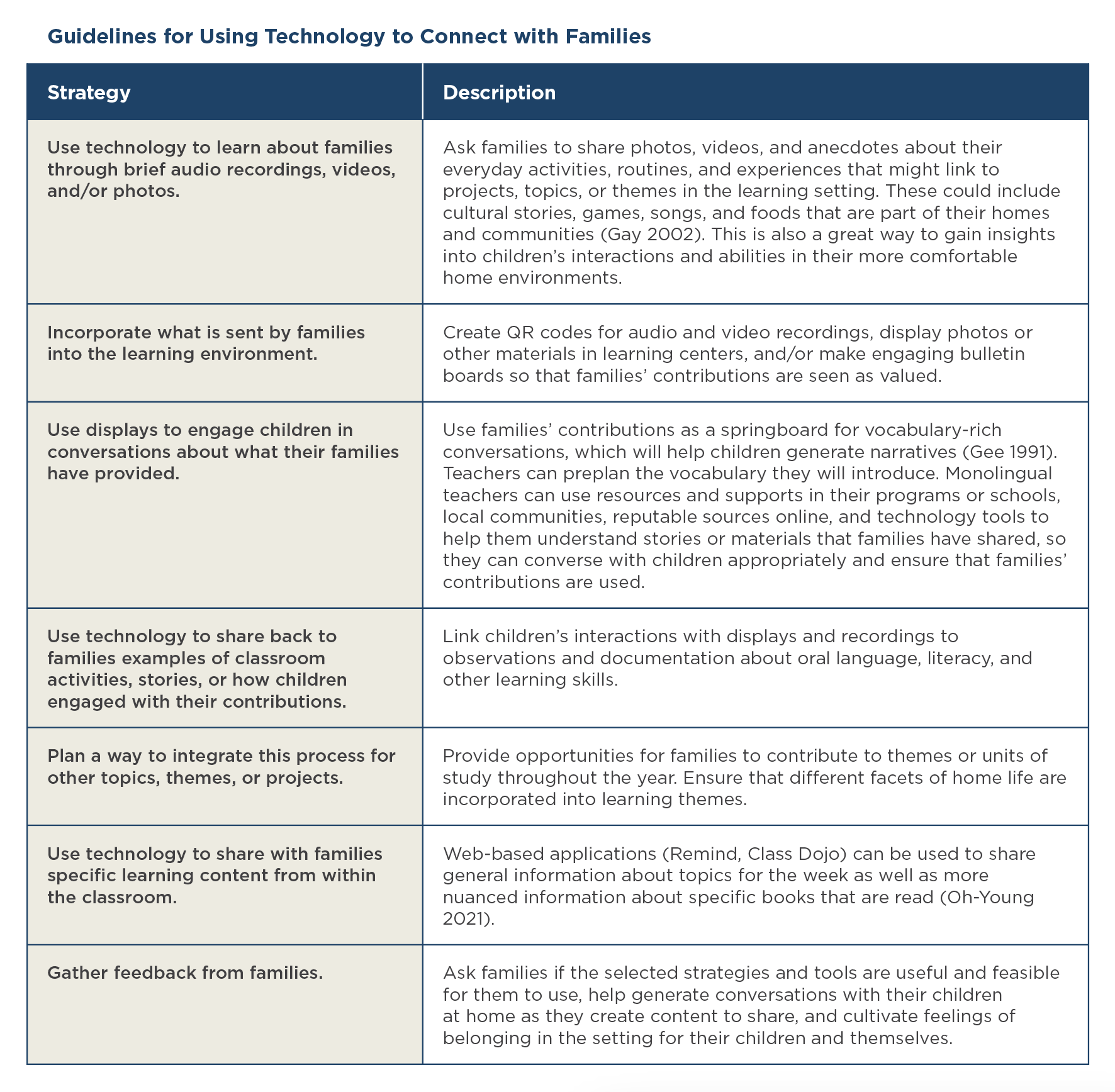

In an effort to increase supports for multilingual learners among Spanish-speaking teachers, NIEER offered a hybrid model of professional development over the course of a school year. During this time, educators used the Self-Evaluation of Supports for Emergent Bilingual Acquisition tool (Figueras-Daniel & Frede 2009) to learn strategies and to reflect on their practices with multilingual learners. Specifically, the tool and training encouraged teachers to select areas of improvement based on their individual needs. Ms. Bernice focused on increasing family engagement in her classroom. As the research partner and professional development training leader, Alexandra brainstormed with her about how to reflect families’ funds of knowledge and how to enrich her unit of study, which was transportation. (See “Guidelines for Using Technology to Connect with Families” at the end of this section.)

The first thing we did was identify books that brought together transportation and families. Choosing books is an important consideration: Children learn from what is displayed and included in learning environments (Gay 2002). Literature that is reflective of children and their experiences gives them opportunities to make connections and engage in conversations comfortably (Axelrod & Gillanders 2016).

We decided on the book My Papi Has a Motorcycle, by Isabel Quintero, among other relevant titles. We used this book to plan an interactive read aloud that would include introducing vocabulary words and using pictures and props to provide concrete representations of those words in English. Because this book is also available in Spanish, Ms. Bernice was able to read it to children in Spanish before reading it in English. This ensured that some comprehension was established before children heard it in the new language.

We then considered ways we could link this classroom theme with families’ lives. To align with My Papi’s story, we decided to ask the children’s families to share a story about a trip they took that highlighted a particular mode of transportation. Knowing that the families in this classroom already used their phones to take pictures, make videos, and post on social media, Ms. Bernice reached out to them via a classroom communication app with the following request:

Can you share a video with a story about a family memory of a trip in a car, bus, motorcycle, train, bike, plane, boat, etc. that you can never forget? . . . This could be a fun road trip with cousins to see family or a trip you used to take with family members to go to school or work. . . . Please describe the mode of transportation and why it was memorable. Make a drawing or collage with your child that includes a picture of the transportation.

Families immediately began sending their videos to Ms. Bernice. As she received them, she created and printed QR codes for each recording during her planning time. Then, as children brought their collages, posters, and pictures to school, she adhered the QR codes to them and displayed them in the library area.

During choice time, Ms. Bernice explained that the code on each poster would lead to a family’s individual story and that children could use the class tablet to activate each one. As children began accessing the codes, Ms. Bernice discussed the stories with them. She asked the children questions about their own stories, compared and contrasted those stories with others, and encouraged children to scan the QR codes on their classmates’ posters. Ms. Bernice also began to map words to her actions: As she scanned images, she shared technical terms (code, link) with the children in Spanish. This presented an important opportunity to name terms that are not often spoken in Spanish in less formal spaces.

Families’ posters included photos of their trips as well as pictures of the modes of transportation they used (buses, planes, minivans). As Ms. Bernice played the videos and recordings, she conversed with children in the language that families used. The children enjoyed seeing and hearing each other’s stories, and they were particularly excited to watch and listen to their own. Besides drawing on research examining the role of oral storytelling for Latino/a families (Reese 2012), these recorded stories allowed Ms. Bernice to intentionally embed family experiences within the classroom (Melzi, Schick, & Scarola 2019). It also afforded the opportunity to see, feel, and hear about families in a respectful way, as families had agency over what they recorded, photographed, and shared.

Seeing the success of this activity, Ms. Bernice attempted to build further home-to-school bridges. In a second communication, she asked families to send in photos and stories about typical modes of transportation in their communities or heritage countries. Some families shared photos of the combis, or buses, used in Mexico for public transportation and the motorbikes used in the Dominican Republic to get to work or school. Other families contributed photos of New Jersey Transit buses and electric scooters. Ms. Bernice used these to create a display for children to visit and talk about.

The children enjoyed seeing and hearing each other’s stories, and they were particularly excited to watch and listen to their own.

While Ms. Bernice introduced new English and Spanish vocabulary during these activities, she also worked to increase children’s knowledge about the nuances between and among various modes of transportation. These activities offered practical ways to expand on what children already knew, and they provided new information about families’ home countries if they were new to the US.

Reflections from the Classroom

Given the positive impact of this activity, I intend to integrate it again in the future. It enriched the classroom experience by making learning more interactive, culturally relevant, and inclusive while fostering stronger connections between students, their families, and the school.

—Ms. Bernice

It is critical for early childhood educators to acknowledge the value of home-to-school opportunities and to intentionally plan meaningful ways to engage families in developmentally appropriate and equitable ways. As Ms. Bernice reflected on her use of technology to connect with families’ funds of knowledge, she noted the following impacts on her practice:

- Enhanced engagement: Children were motivated to participate in the learning activities. Because they involved families and personal experiences, activities were more meaningful.

- Cultural and linguistic inclusivity: Encouraging families to share stories in their home languages made the classroom more inclusive and honored the children’s diverse linguistic backgrounds. This helped create a more welcoming and culturally sensitive learning environment.

- Stronger family-school connections: Because families were directly involved in the learning process, Ms. Bernice showed that she valued their contributions and that educating their children was a collaborative effort.

- Improved language and social skills: Besides listening to their families’ stories, children also shared their experiences with peers. They interacted and collaborated as they watched each other’s videos, looked at posters, and discussed their families’ trips. This helped develop their language skills, encouraged them to engage in conversations with each other, and fostered their understanding of others’ knowledge and experiences.

- Vocabulary and concept development: Children were able to apply and reinforce the vocabulary words they learned in school to a real-life context. Such opportunities to extend children’s vocabulary in connected ways support the building of background knowledge that links to later reading comprehension skills that are necessary for success in early elementary grades and beyond (Gillanders, Castro, & Franco 2014).

By reflecting on the practices that supported multilingual learners in her setting, Ms. Bernice was able to think more broadly about how to connect her classroom themes and instruction with children’s families in meaningful ways. Through this work, she considered ways to more regularly partner with and incorporate families into her classroom without creating hurdles that would make it difficult for everyone to participate. She was able to learn and apply ideas about the intentional use of technology to help her achieve these goals.

To apply these lessons to their own settings, we suggest educators consider the following:

- How can a culture of valuing families be elevated during orientation or when families first enroll in a program?

- Are children’s families, home lives, and cultures intentionally brought into classroom themes in an ongoing way over the school year?

- In what practical ways can educators incorporate audio recordings, videos, and/or pictures to bring children’s home lives, experiences, cultures, and languages to every theme or unit of study?

Photograph: courtesy of Bernice Vasquez

Copyright © 2024 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

Axelrod, Y., & C. Gillanders. 2016. “Culturally Relevant Literature for Latino Children in the Early Childhood Classroom.” In Multicultural Literature for Latino Bilingual Children: Their Words, Their Worlds, eds. E.R. Clark, B.B. Flores, H.L. Smith, & D.A. González, 101–20. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Castro, D.C., L. Espinosa, & M. Páez. 2011. “Defining and Measuring Quality in Early Childhood Practices That Promote Dual Language Learners’ Development and Learning.” In Quality Measurement in Early Childhood Settings, eds. M. Zaslow, I. Martinez-Beck, K. Tout, & T. Halle, 257–80. Towson, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Choi, J.Y., D. Ryu, C.K. Van Pay, S. Meacham, & C.C. Beecher. 2021. “Listening to Head Start Teachers: Teacher Beliefs, Practices, and Needs for Educating Dual Language Learners.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 54 (1): 110–24.

Figueras-Daniel, A., & E. Frede. 2009. Self-Evaluation of Supports for Emergent Bilingual Acquisition. New Brunswick, NJ: NIEER.

García, E.E., & E.C. Frede, eds. 2010. Young English Language Learners: Current Research and Emerging Directions for Practice and Policy. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Gay, G. 2002. “Preparing for Culturally Responsive Teaching.” Journal of Teacher Education 53 (2): 106–16.

Gee, J.P. 1991. “A Linguistic Approach to Narrative.” Journal of Narrative and Life History 1 (1): 15–39.

Gillanders, C., D.C. Castro, & X. Franco. 2014. “Learning Words for Life: Promoting Vocabulary in Dual Language Learners.” The Reading Teacher 68 (3): 213–21.

Hall, C.M., & K.L. Bierman. 2015. “Technology-Assisted Interventions for Parents of Young Children: Emerging Practices, Current Research, and Future Directions.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 33 (4): 21–32.

Hung, H.-T. 2018. “Gamifying the Flipped Classroom Using Game-Based Learning Materials.” ELT Journal 72 (3): 296–308.

Iruka, I.U. 2019. “Supporting Families of Young Children in the 21st Century: Charting a New Evidence-Based Direction.” In APA Handbook of Contemporary Family Psychology: Applications and Broad Impact of Family Psychology, eds. B.H. Fiese, M. Celano, K. Deater-Deckard, E.N. Jouriles, & M.A. Whisman, 249–66. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Melzi, G., A.R. Schick, & L. Scarola. 2019. “Literacy Interventions That Promote Home-to-School Links for Ethnoculturally Diverse Families of Young Children.” In Ethnocultural Diversity and the Home-to-School Link, eds. C.M. McWayne, F. Doucet, & S.M. Sheridan, 123–43. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Cham.

Méndez, L.I., E.R. Crais, D.C. Castro, & K. Kainz. 2015. “A Culturally and Linguistically Responsive Vocabulary Approach for Young Latino Dual Language Learners.” Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 58 (1): 93–106.

Moll, L.C. 1992. “Bilingual Classroom Studies and Community Analysis: Some Recent Trends.” Educational Researcher 21 (2): 20–24.

Mowafi, Y., & I. Abumuhfouz. 2021. “An Interactive Pedagogy in Mobile Context for Augmenting Early Childhood Numeric Literacy and Quantifying Skills.” Journal of Educational Computing Research 58 (8): 1541–61.

NAEYC. 2019. “Advancing Equity in Early Childhood Education.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. NAEYC.org/resources/position-statements/equity.

NAEYC. 2020. “Developmentally Appropriate Practice.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. NAEYC.org/resources/position-statements/dap/contents.

NAEYC. 2022. Developmentally Appropriate Practice in Early Childhood Programs Serving Children from Birth Through Age 8. 4th ed. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

NAEYC & Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media. 2012. “Technology and Interactive Media as Tools in Early Childhood Programs Serving Children from Birth Through Age 8.” Joint position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. NAEYC.org/resources/topics/technology-and-media/resources.

NASEM (National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2017. “Promising and Effective Practices for English Learners in Grades Pre-K to 12.” In Promoting the Educational Success of Children and Youth Learning English: Promising Futures, 291–336. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Neuman, S.B., T. Kaefer, & A. Pinkham. 2014. “Building Background Knowledge.” The Reading Teacher 68 (2): 145–48.

Oh-Young, C. 2022. “Utilizing Quick Response Codes to Extend Instruction in Early Childhood Contexts.” Young Exceptional Children 25 (4): 195–206.

Paris, D., & H.S. Alim, eds. 2017. Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Park, M., J. Zong, & J. Batalova. 2018. “Growing Superdiversity Among Young US Dual Language Learners and Its Implications.” Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

Ray, A., B. Bowman, & J. Robbins. 2006. Preparing Early Childhood Teachers to Successfully Educate All Children: The Contribution of Four-Year Undergraduate Teacher Preparation Programs. New York, NY: Foundation for Child Development. fcd-us.org/preparing-early-childhood-teachers-to-successfully-educate-all-children.

Reese, L. 2012. “Storytelling in Mexican Homes: Connections Between Oral and Literacy Practices.” Bilingual Research Journal 35 (3): 277–93.

Ryan, S., D.J. Ackerman, & H. Song. 2005. “Getting Qualified and Becoming Knowledgeable: Preschool Teachers’ Perspectives on Their Professional Preparation.” Unpublished manuscript. Rutgers: The State University of New Jersey.

Tabors, P.O. 1997. One Child, Two Languages: A Guide for Early Childhood Educators of Children Learning English as a Second Language. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

Thorne, T. 2016. “Augmenting Classroom Practices with QR Codes.” TESOL Journal 7 (3): 746–54.

Williams, C., S. Meek, M. Marcus, & J. Zabala. 2023. “Ensuring Equitable Access to Dual-Language Immersion Programs: Supporting English Learners’ Emerging Bilingualism.” New York, NY: The Century Foundation. production-tcf.imgix.net/app/uploads/2023/05/22163437/conor_report.pdf.

Alexandra Figueras-Daniel, PhD, is an assistant research professor and bilingual early childhood education senior policy specialist at the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER). Alex engages in work seeking to support multilingual learners in early childhood education classrooms and has worked on a number of projects, including partnerships with programs and teachers. [email protected]

Bernice Vasquez is a preschool teacher at Casimir Pulaski School #8 in Passaic, New Jersey. Bernice has worked in early childhood for the past 17 years. [email protected]