The Command Center Project: Resolving My Tensions with Emergent Curriculum (Voices)

You are here

Thoughts on the Article | Daniel Meier, Voices Executive Editor

With the increasingly complex array of curricular choices in early childhood education, teachers and administrators are constantly evaluating the most effective models, approaches, and materials to support children’s learning. As Luvy Vanegas-Grimaud shows in this insightful and genuine article, the process of teacher inquiry and reflection is a critical lens for finding one’s place in a new curriculum, and evaluating its worth for self, children, and families. Luvy, like many educators, had moved from a more structured, academic-based teaching environment to a new school with a more play-based, emergent curriculum approach. Through the time-honored teacher research tools of close observation, written notes of children’s actions, photographs of their constructions, and documentation of children’s conversations, Luvy reorients her “inner teaching self” to the external realities of her new environment and context. By listening closely to the children’s interest in creating a space command center, and watching and participating in their unfolding constructions, Luvy honors the children’s innermost learning desires and affirms her own commitment to early childhood education as the critical foundation for empowering and transformative education for children and adults. Luvy’s is an honest and open account of this process—and a testament to the power of teacher research for sharing one’s innermost concerns, fears, and doubts, as well as joys and triumphs

“Let’s make a mission control center!,” Anne says. “Yeah! Let’s make a control center!” the rest of my preschool class eagerly agrees. “Don’t we want to learn about astronauts first?” I ask. “No. We want to learn about mission control first! We don’t want to learn about astronauts anymore,” Doug responds. I try to quiet the voice in my head: But what about the books I found on astronauts and the plans I made?

Having taught preschool for 13 years, I have long thought of myself as a teacher who follows and respects the interests of the children in my class. However, when my 23 three- to five-year-old students abruptly shifted from astronauts to mission control, my immediate fear and resistance revealed to me how uncomfortable I was with changing our focus. I kept wondering, “Now what? What do I do next?” When my two coteachers and I introduced the original astronaut project, I had a plan in mind. Faced with this shift to mission command centers, I felt lost and as if I had to start all over from scratch.

As an early childhood educator, I have thought of myself as an emergent teacher who follows my students’ lead and supports their explorations. In the past, had I truly followed the children’s lead? Or did I assume what they wanted to learn and then develop activities of my choice?

As a result of these questions and reflections, I decided to conduct a self-study of my teaching practices and how they support child-initiated projects. My students were expressing a strong desire to engage in the inquiry process and learn more about command centers. I wanted to support them in the best way possible, but I struggled with the sudden change. I had to remember that one of my personal teaching goals was to support them. Wanting to support their learning process, I decided my research questions would be:

- How can I help children carry out their emergent project without directing their learning?

- How can I support their enthusiasm for inquiry while still providing them with valuable learning experiences?

Framing my study

Revisiting the literature on emergent curriculum reminded me about the importance of keeping an open mind, avoiding leading the children down my preferred path, and assisting the children in making meaning of their learning journey (Dutton 2012).

Given my questions about my teaching practices, I focused on accepting that project work grows in many directions and with no predefined progression, and that no outcomes are decided before the journey even begins (Rinaldi 2006).

When I prepared for the astronaut project, I had a desired outcome in mind before the children had had an opportunity to engage in the learning process. If I had insisted on my astronaut project, it seems likely that the children’s wonder and curiosity would have decreased because their interests and questions would not be driving the curriculum (Dutton 2012). I wanted to engage in learning with my students (Ballenger 1999), no longer allowing my predetermined plans or insecurities to direct their learning.

Having decided on a teacher research project, I engaged in systematic inquiry to evaluate my teaching practices (Meier & Henderson 2007). I had never before undertaken self-study to challenge my methods, values, and goals as an educator. I wanted to adopt a more reflective practice, to deliberately scrutinize my work and thoughts (Perry, Henderson, & Meier 2012), and to begin a process of ongoing redefinition and renewal (Stremmel 2002).

Research design

My self-study took place in a play-based, emergent, year-round preschool in Berkeley, California, where I had been employed for two years prior to the study. It stretched through the spring semester, beginning in January and ending in May. The fall semester had been dedicated to helping the children transition into the program.

In the past, had I followed the children’s lead? Or did I assume what they wanted to learn?

Over the course of the study, I collected qualitative data in several ways. Each day, I wrote journal entries in which I recorded my feelings and perspectives on the children’s progress and ideas, and I focused on my role in their activities. I also made detailed notes on a weekly basis about the children’s activities and play related to their mission control project. Photographs, videos, and audio recordings of the children’s interactions with one another and with me were taken by my coteachers and myself. My data collection did not disrupt the children’s daily routines. I transcribed the recorded conversations and found that reading and reviewing the transcriptions was valuable in identifying my role.

I had never before undertaken self-study to challenge my methods, values, and goals.

To identify and analyze emergent themes in the data, I reviewed them daily and weekly throughout the course of the study. I created and applied codes to track repeated concepts, then reviewed my coded data to identify overarching themes. Three themes emerged in relation to my teaching role: (1) children’s level of engagement and focus; (2) teacher’s actions; and (3) teacher’s tensions.

Research findings

My most important findings identified the tensions I experienced throughout the course of the study and how my becoming aware of these influenced my actions as a teacher. These tensions and feelings of insecurity caused me to second guess my students’ commitment and ability to direct their own learning. I wanted to be the one in control. I wanted to be the one to teach them what I thought they should know and as a result I found myself wanting to take over. Seeing my role in a new light, I reconnected with viewing and treating my students as my learning partners.

Teaching is a journey that requires constant reevaluation to stay true to one’s teaching philosophy. My journey required me to take a closer look at my reluctance to give up control. I learned how important it is for the teacher to trust that children are capable of forming their own learning (Dutton 2012).

Children’s engagement and focus

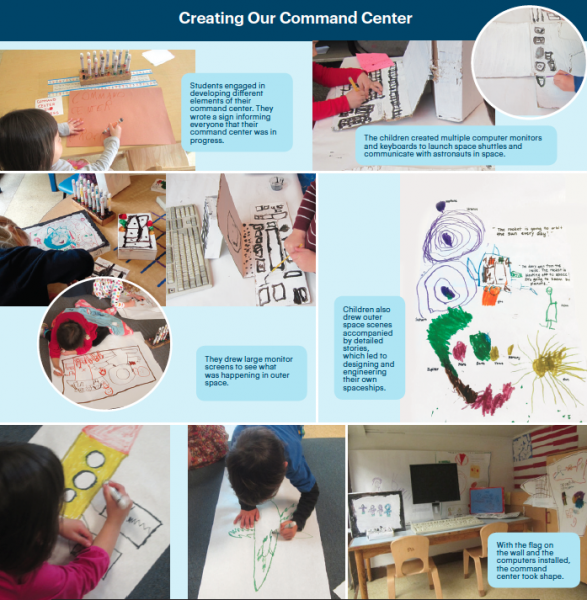

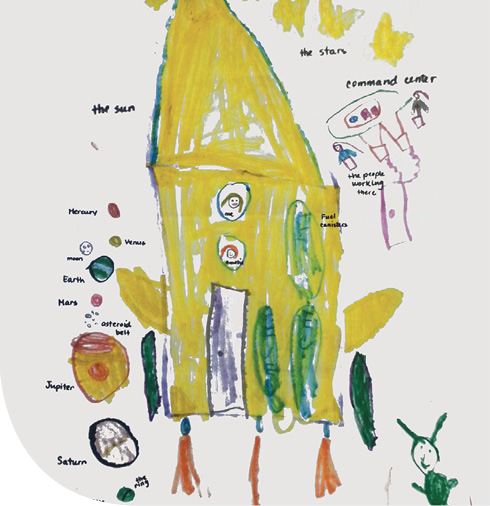

Even after my initial fear of shifting from astronauts to mission control subsided, I remained hesitant. I thought my students would be unable to focus enough to maintain interest in, and derive meaningful learning from, their project. I believed that as one of their teachers, I had to “teach” them—which meant redirecting them back to learning about astronauts. Little did I know that by allowing the children to engage in their emergent project I would see them focus at levels I had not seen before. John Dewey (1962) suggested that adults play a key role in supporting and guiding children’s interests. The moment I decided to follow the children’s lead and help them create their command center, I took on the role of supporter and guide, fostering opportunities for them to do their best work. Their focus, research, knowledge, and skills are documented in the photo story “Creating Our Command Center.”

Reflecting on my role

The photographs capture the intensity and focus that the children demonstrated while creating the different parts of their command center. As I reflected on the beginning of the project, I realized that my feelings of insecurity and need to control almost prevented me from experiencing what my students were capable of doing.

Becoming aware of the tensions I experienced influenced my actions. Realizing that this project belonged to the children, not to me, I wondered how I could help them without taking over. I began to observe and listen closely to see where and how I could extend their learning. By regularly analyzing my data, I discovered that my observations and listening were extremely valuable—I took advantage of teachable moments across several learning domains while respecting the children’s ownership of their command center and learning about outer space. The excerpts on pp. 64–67 come from my observation notes, photographs, and journal.>

Resolving my tensions

Data excerpt #1—Journal entry (01-30-14)

I don’t know what happened today. The children completely changed the focus of the project. I don’t completely understand when they changed their minds. We asked them what they wanted to learn about, and they all agreed on astronauts. We even made a big deal about it and had Vicky dress up like an astronaut. I guess the book Anne brought in changed their minds. It had a picture of a command center and I guess it sparked their interest. I have no idea how to proceed. I tried to change their minds, but they were not listening to what I was saying. I really want to support their project, but I guess I’m going to have to take a different approach now. I’m going to have to follow their lead and see where it goes.

Data excerpt #2—Journal entry and observation photo (02-03-14)

Dillan, Anne, Chris, and Nick are working collaboratively to move the furniture around in the downstairs part of our loft. They unanimously decided that they wanted to create a mission control center after reading Anne’s book. I guided them by providing pictures of different mission control centers. I printed them out so that they could use them as references. As the children looked at the pictures, they realized that they had to rearrange the furniture in the area if they wanted to create a mission control center. Together, they began to move furniture around and along the wall. They assigned roles to one another, letting each other know which piece of furniture they were going to move and where they were going to move it to. I tried really hard not to step in and take over their activity. Instead, I simply watched and made sure they were moving the furniture safely. I observed them closely. They kept saying, “We have to move this to the wall so there’s room, right guys?” “Yeah!,” they all responded. It’s amazing to see how children work together when we give them the chance to do so. Not taking over was the best thing I could have done for them. It allowed them the opportunity to work together and to strengthen the sense of community that we are trying to instill in our class.

These excerpts highlight the shift of emotions I slowly experienced during the project. Initially, my goal was to assist the children in their learning, but I couldn’t help but feel disappointed by the shift in their interests. I was truly excited about astronauts and didn’t know how to begin supporting their curiosity about mission control centers. Regardless of my emotions, discouraging their project was the last thing I wanted to do.

As the project progressed, I saw that the children were engaging in valuable activities without my direction, and I found myself becoming excited about their work. Reflecting on my changing role, I realized that children are at the forefront of teacher research, not me. Teacher research is designed to help teachers gain new ways of seeing children and become more responsive to them (Perry, Henderson, & Meier 2012). Revisiting my data revealed to me that I used the word I repeatedly: I wanted, I felt, I didn’t agree. That was the moment I stepped back and truly began to listen and observe.

Observing and listening

Data excerpt #3—Observation notes (02-05-14)

Alice and Anne are looking at pictures of an actual command center that I printed out. Standing in front of the pictures, they point and move in closer, trying to see something. I approach them without interrupting and overhear their conversation.

Alice and Anne are looking at pictures of an actual command center that I printed out. Standing in front of the pictures, they point and move in closer, trying to see something. I approach them without interrupting and overhear their conversation.

Anne: Yeah, look. There’s a whole bunch, Alice.

Alice: There’s a phone and lots and lots of buttons. [Pointing to the buttons]

Anne: We need buttons, lots of buttons. And look, there’s lots of big screens. Big ones like at the movies; and look, they can see the astronauts in space.

Alice: I have a computer at home and it has lots of buttons too!

Data excerpt #4—Teacher journal entry (02-05-14)

Today I observed Anne and Alice closely observing the command center pictures I posted in our dramatic play area. They are beginning to realize that if they want to create a command center, they have to look at the pictures to see the elements in an actual command center. The command center has been  abandoned the last few days, and I’m glad to see that they haven’t lost interest. I don’t want to tell them what to do, but perhaps I should ask the students to make a list of what command centers need and see what they come up with. Anne already expressed the need for lots of buttons. Perhaps they want to make a few things!

abandoned the last few days, and I’m glad to see that they haven’t lost interest. I don’t want to tell them what to do, but perhaps I should ask the students to make a list of what command centers need and see what they come up with. Anne already expressed the need for lots of buttons. Perhaps they want to make a few things!

By closely listening to Anne and Alice’s conversation, I was later able to reflect on how I could assist them and value what they wanted to do without telling them what they needed. I was also able to extend my own learning, grasping on a deeper level that the act of listening gives value to others’ views (Rinaldi 2006).

I decided to ask the children at circle time what items they needed in order to create their command center. As we observed and compared the pictures from the Internet, they came up with an extensive list of items. Their project was officially under way. And my role was becoming clearer. I sought to help the class select topics at the right level of focus and become the facilitator and resource gatherer (Meier & Henderson 2007). I became a dispenser of occasions, helping my students—my learning partners—plan what came next (Edwards 2012).

Taking advantage of teachable moments

Data excerpt #5—Observation (02-25-14)

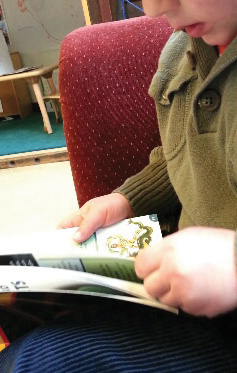

I’m inside the classroom observing two friends in the mission control center. Leo approached me with a book about space we had on our bookshelf.

Leo: Look, this book is good for learning. [He shows me a picture of a double star. I immediately stop what I’m doing and give him my undivided attention.]

Me: Why is it good for learning?

Leo: Because it talks about space.

Me: Oh, okay! Let’s go sit down and look at it.

Leo: Yeah, let’s read it! [We walk over to the couch, and Leo begins to turn the pages of the book. We continue to turn the pages and Leo continues to ask questions.]

Leo: What is this?

Me: Constellations. It says right here, “constellations.”

Leo: What is this guy doing? [pointing to the Orion constellation on the page]

Me: That’s Orion, the hunter. [Leo turns the page]

Me: Leo! Look! It’s Leo! There’s a constellation called Leo. Just like your name. [Leo begins to smile]

Leo: Yeah!

Me: It says “Leo the Lion.”

Leo: Oh, I’m called that!

As I reflected on my interaction with Leo, I realized that my reaction to his excitement about the book he found reinforced and supported his desire to know more. I saw clearly that the teacher’s attitudes can encourage or discourage a child’s attitude toward learning (Elkind 2007). By giving full attention to Leo’s discovery and devoting time to looking at the book together, I showed Leo that I cared about his acquisition of knowledge. This interaction also made me more aware of my students’ commitment to their project.

As I reflected on my interaction with Leo, I realized that my reaction to his excitement about the book he found reinforced and supported his desire to know more. I saw clearly that the teacher’s attitudes can encourage or discourage a child’s attitude toward learning (Elkind 2007). By giving full attention to Leo’s discovery and devoting time to looking at the book together, I showed Leo that I cared about his acquisition of knowledge. This interaction also made me more aware of my students’ commitment to their project.

They were learning to use books as references and discovering that they could engage in inquiry. I realized that I was supporting—not directing—Leo’s learning. I read the words and transmitted information back to Leo under his guidance. We were sharing in the construction of knowledge (Cuffaro 1995).

Data excerpt #6—Journal entry (03-08-14)

Today, Alice and Carly noticed that there was an American flag in one of the command center pictures. Alice said, “Look, there’s a flag in this picture.” I asked them if they would like to make a flag, and they responded yes. I asked them what we could use to look at the flag closely, and Carly answered, “I know, the backpack!” She remembered that Vicky’s backpack had the American flag on it. We got the backpack and put it on the chair. I asked them what we needed for the flag, and they said, “Stars, red paper, blue paper, white paper, and stripes,” while they looked at the flag. We didn’t have stripes or stars, so they decided to make their own.

They got excited when I told them they would have to draw their own 50 stars and 13 stripes. They counted and I provided rulers. They did such a great job. Ellie and Anne joined in once they saw what the others were doing. Together, they drew 50 stars, cut them out, and lined them up in rows, using the flag on the backpack as a guide. They counted the number of red and white stripes they needed and created them, as well. I explained that rulers were used for measuring and to draw straight lines. Carly used the ruler to make her stripes.

Joining in the children’s excitement and curiosity about the American flag led to another teachable moment to use to develop a variety of skills and knowledge. Through the flag creation, I challenged my students without telling them what to do. Instead, I asked them questions to get them thinking about what they needed, which inspired further creativity and curiosity (Gallenstein 2005). With simple but intentional prompts, I incorporated counting, measuring, and patterning.

Discussion

Giving up control of the project focus was difficult; it challenged me to reexamine who I was as an educator. I discovered that the tensions I was experiencing indicated I had followed my own agenda in the past. My students challenged me to become a better observer and listener, which in turn revealed teachable moments and allowed me to extend their learning.

Giving up control of the project focus was difficult; it challenged me to reexamine who I was as an educator. I discovered that the tensions I was experiencing indicated I had followed my own agenda in the past. My students challenged me to become a better observer and listener, which in turn revealed teachable moments and allowed me to extend their learning.

My insecurity almost prevented me from experiencing what my students were capable of doing.

This study helped me reconnect with and more fully understand reflective teaching. After this experience—and with my data as a reminder—I will never forget that letting go of control, even when feeling insecure about it, means being able to give children ownership of their own learning.

References

Ballenger, C. 1999. Teaching Other People’s Children: Literacy and Learning in a Bilingual Classroom. Practitioner Inquiry series. New York: Teachers College Press.

Cuffaro, H.K. 1995. Experimenting with the World: John Dewey and the Early Childhood Classroom. Early Childhood Education series. New York: Teachers College Press.

Dewey, J., & E. Dewey. [1915] 1962. Schools of Tomorrow. New York: E.P. Dutton.

Dutton, A.S. 2012. “Discovering My Role in an Emergent Curriculum Preschool.”Voices of Practitioners 7 (1): 3-17.

Edwards, C. 2012. “Teacher and Learner, Partner and Guide: The Role of the Teacher.” Chap. 9 in The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Experience in Transformation, 3rd ed., eds. C. Edwards, L. Gandini, & G. Forman,

Elkind, D. 2007. The Power of Play: Learning What Comes Naturally. Berkeley, CA: Da Capo.

Gallenstein, N.L. 2005. “Engaging Young Children in Science and Mathematics.” Journal of Elementary Science Education 17 (2): 27-41.

Meier, D.R., & B. Henderson. 2007. Learning from Young Children in the Classroom: The Art and Science of Teacher Research. New York: Teachers College Press.

Perry, G., B. Henderson, & D.R. Meier, eds. 2012. Our Inquiry, Our Practice: Undertaking, Supporting, and Learning from Early Childhood Teacher Research(ers). Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC).

Rinaldi, C. 2006. In Dialogue with Reggio Emilia: Listening, Researching, and Learning. Contesting Early Childhood series. New York: Routledge.

Stremmel, A.J. 2002. “The Value of Teacher Research: Nurturing Professional and Personal Growth through Inquiry.” Voices of Practitioners 2 (3): 1-9.

Photographs: pp. 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, courtesy of the author; 4, 5, courtesy of NASA

Luvy Vanegas-Grimaud, MA, is an adjunct professor in the Department of Child Development at Merritt College, in Oakland, California, and concurrently works at University of California, Berkeley’s Early Childhood Education Program. Luvy is actively involved in various international teacher trainings, particularly for preschool educators in Latin America and China. She is a member of the Early Childhood Education Community with Action Research Network of the Americas (ARNA).