Expanding the Lens—Leadership as an Organizational Asset

You are here

Strong leadership is a vital component of any thriving organization, and early care and education programs are no exception. An emerging body of research confirms the pivotal leadership role early childhood administrators play in their centers’ quality equation (Bloom & Bella 2005; Lower & Cassidy 2007; MCECL 2010; Rohacek, Adams, & Kisker 2010; Dennis & O’Connor 2013). Focusing on the background, beliefs, dispositions, and actions of early childhood administrators is certainly appropriate, given their extraordinary influence on the factors that impact children’s development and learning—such as hiring qualified teachers, setting expectations for adult-child interactions, and shaping a program’s educational philosophy and vision. Yet it is also useful to expand the lens to think about leadership as an organizational asset and consider the role administrators play in nurturing leadership capacity at all levels of the organization.

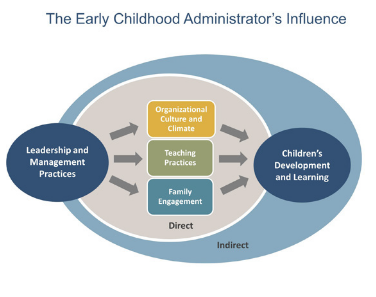

In viewing leadership from these two perspectives, this article first presents a framework for thinking about the many ways early childhood administrators influence the quality of their programs. It then looks more broadly at the concept of distributed leadership, in which leadership is viewed as an asset that is valued and practiced by many in an organization.

The administrator’s influence

Early childhood administrators’ roles are as varied as the field itself. Director, site manager, and principal are but a few of the titles administrators use to identify themselves. Early childhood administration clearly includes both leadership and management functions (NAEYC 2005; Talan & Bloom 2011). Leadership functions relate broadly to helping an organization clarify and affirm values, set goals, articulate a vision, and chart a course to achieve that vision. Management functions relate to orchestrating tasks and developing systems to carry out the organizational mission. The everyday leadership and management practices directly affect the culture and climate of the center, the teaching practices, and the level and quality of family engagement. These elements, in turn, impact children’s development and learning (see “The Early Childhood Administrator’s Influence” below).

© McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, National Louis University

Organizational culture and climate

The culture of an early childhood setting is what makes it unique. Culture includes the shared values, assumptions, and collective beliefs about what is important, and the norms and expectations for what is appropriate and acceptable in everyday interactions. Culture also includes the traditions, rituals, celebrations, and customs that distinguish one program or school from another. An early childhood setting’s organizational climate is slightly different from its culture. Organizational climate is the staff’s collective perceptions of what the organization is like in terms of policies, practices, procedures, and routines. Culture and climate are complementary concepts with overlapping, yet distinguishable, nuances of organizational life (Ostroff, Kinicki, & Muhammad 2013).

Research suggests elementary school principals influence student learning through school culture and climate. Students achieve higher scores on standardized tests in schools with healthy cultures and climates (MacNeil, Prater, & Busch 2009)—that is, in schools that promote high academic standards, provide adequate resources, and maintain stability while being responsive to the demands of the external environment. Principals influence student achievement by influencing the school context: they shape school goals, policies, practices, and social networks. Similarly, early childhood programs that have a culture of high expectations and accountability for staff, norms of continuous quality improvement, and shared beliefs about the value of collaboration and ethical practice are in a strong position to support children’s development and learning (Bloom, Hentschel, & Bella 2013; Bloom 2014).

In writing about sustainable workplaces (i.e., workplaces that nurture teachers’ passion and purpose), Eklund (2009) emphasizes the importance of creating a work climate that recognizes, addresses, and celebrates the good work of staff—a work environment that welcomes laughter, collegiality, and freedom to innovate. A sustainable workplace is similar to what Kahn (2005) refers to as a resilient caregiving organization, a place where adults are supportive of and supported by colleagues.

Teaching practices

Teachers impact children’s experiences directly by their daily actions in the classroom, but center directors impact children’s development and learning by structuring the conditions that support teacher effectiveness. The decisions they make related to hiring, supervision, professional development, and performance appraisal all influence teachers’ capacity to carry out their roles. Even routine decisions about work schedules affect whether teachers have time to work together to strengthen their practice and promote each other’s learning.

In their synthesis of the research on school principals’ influence, Clifford, Behrstock-Sherrat, and Fetters (2012) document the ripple effect of principals’ leadership, noting the direct and indirect ways that principals affect teachers and students. For example, a principal’s decision about the allocation of funds for technology affects teachers’ access to instructional resources that impact children’s learning.

Wahlstrom and colleagues (2010) found that principals account for approximately 25 percent of a school’s influence on student achievement, second only to teachers. Moreover, while teachers impact the children in their classroom, principals impact all the children in the school (Branch, Hanushek, & Rivkin 2013).

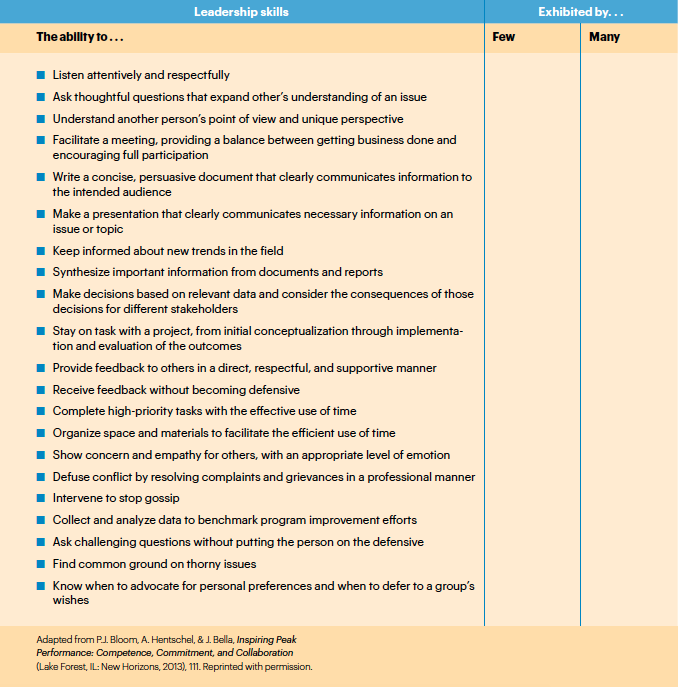

Leadership Skills Inventory

In high-performing organizations, a wide range of staff have leadership skills, regardless of their roles or titles. By using the inventory below administrators can assess whether specific skills are displayed by a few or by many in the center.

The ripple effect is evident in settings that serve children from birth to 5 years old as well. Administrators who are instructional leaders help teachers become more intentional in setting up the learning environment, creating an engaging child-centered curriculum, and using data to make informed decisions about how to best support each child’s learning (Skiffington, Washburn, & Elliott 2011). As instructional leaders, directors influence classroom practices by providing feedback to teachers, allocating resources for professional development, establishing peer learning teams, and promoting reflection. This is particularly critical in early care and education settings because many teachers enter the field with little or no preparation (Nicholson & Reifel 2011).

Teachers are more likely to stay if they see themselves as part of a team supported by leadership and if they have influence over their work environment.

It is well documented that working conditions and responsive supervision can have a profound impact on teachers’ ability to effectively carry out their roles. The availability of breaks, preparation time, instructional resources, supportive coaching, and, of course, adequate compensation, all have an impact on teachers’ levels of commitment to their jobs and to their centers (Whitebook et al. 2009).

Allensworth (2012) found that the quality of the work environment strongly predicts whether teachers remain in their jobs. Teachers are more likely to stay if they see themselves as part of a team supported by leadership. Teachers are also more likely to stay if they feel they have influence over their work environment. Summing up the research in this area, Daniel Muijs and colleagues state, “Whatever else is disputed, the contribution of leadership to improving organizational performance and raising achievement remains unequivocal” (2004, 157).

Family engagement

Evidence is clear that parents and other guardians are an integral piece of the quality equation in early childhood programs. A review of 100 studies focusing on literacy, math, and social and emotional skills of children from diverse backgrounds found that many children tend to do better academically and socially in preschool, kindergarten, and the early grades when their families are more involved (Van Voorhis et al. 2013). The director’s role in shaping expectations for family engagement and communicating a positive and welcoming message is critical. Hilado, Kallemeyn, and Phillips (2013) found that administrators who have a more flexible definition of parent involvement tend to have more positive views of parents and perceive higher levels of involvement.

Bornfreund (2014) emphasizes that random acts of encouraging family involvement is not enough. Simply inviting parents to center celebrations, distributing a newsletter, or creating a parent resource room isn’t likely to lead to improved outcomes for children. Effective family–center partnerships include ongoing, individualized communication; data sharing about children’s learning; home visits; and multiple opportunities for families to be involved at the center and classroom levels. Administrators’ best family engagement efforts are linked to children’s learning—family involvement helps families understand what their children should know and be able to do. Effective administrators also embrace a philosophy of partnership in which they share power and responsibility with families.

In high-quality programs, directors implement policies and practices that honor differing family structures, involve parents and guardians in decisions relating to their children, and regularly solicit families’ feedback about the quality of their children’s experiences. When family engagement is a high priority, directors actively seek parents’ support and assistance and work to reduce barriers, such as families’ lack of transportation to the program and differing languages in home–school communication. They encourage teachers to make families a visible presence in their classrooms, and to make the life of the classroom visible to families by documenting children’s daily experiences.

Cultivating leadership in others

Jack Welch, who ran General Electric for years, addresses the notion of building leadership capacity in his autobiography, Winning. He says, “Before you are a leader, success is all about growing yourself. When you become a leader, success is all about growing others” (2005, 61). Building leadership capacity requires a shift from thinking about a model of leadership in which authority resides in a single heroic figure to thinking about a model of distributed leadership— a model in which leadership is practiced by many staff at a program, who share responsibility and accountability. In this broader view, leadership is viewed as a fluid organizational asset—an asset that is not fixed but instead can be strengthened and expanded. Thinking metaphorically about these ideas means shifting from the typical hierarchical paradigm (leadership resides at the top) or from a wheel configuration (the center hub represents the leader) to a network configuration in which each node is vital for maintaining the strength and viability of the entire web.

Ensuring a program’s sustainability

Expanding leadership capacity helps ensure a program’s sustainability. Every center needs a comprehensive leadership succession plan to ensure a smooth transition when the administrator leaves. A leadership succession plan is an organization’s deliberate and systematic effort to ensure leadership continuity. It can help an organization develop and retain its most capable staff, preserve the program’s institutional memory, and ensure that the organization continues to meet all its legal obligations. A survey of 401 early childhood directors found that only 27 percent felt they were well prepared to handle the range of tasks required of them when they first assumed their administrative roles (Bloom 2014). This is not surprising given that most directors are promoted to the administrative level from teaching positions. Their classroom experience simply does not prepare them for leading and managing others. Making an intentional effort to expand a program’s leadership capacity helps ensure a broader pool of leadership talent is available when the time comes to turn over the reins, avoiding chaos in the transition.

Getting started

While many early childhood administrators readily embrace this broader concept of leadership, putting it into practice is another matter. Some have difficulty sharing their power, preferring instead to keep tight control over influence and decision-making authority. Others are not confident that staff can live up to their expectations. And still others are reluctant to share leadership authority because they worry about overloading staff with administrative responsibilities when teachers’ primary focus should be on teaching (Talan 2010). The irony is that by strengthening a program’s overall leadership capacity, administrators are more likely to improve staff morale, build a collaborative spirit, and reduce disruptive turnover.

Administrators who are interested in the idea of distributed leadership and wonder where their programs stand in terms of collective leadership capacity can complete the “Leadership Skills Inventory” shown above. It provides a quick assessment of a program’s capacity as it relates to several essential leadership skills.

By examining the results of this informal inventory of leadership skills, administrators can identify organizational strengths and create opportunities to take advantage of the center’s collective leadership capacity. The results also reveal areas where the combined abilities of the staff could be improved. Targeted professional development can then increase individual and group capabilities. In areas where only a few individuals demonstrate leadership skills, administrators can create systems to ensure that distributed leadership becomes an organizational norm.

Conclusion

There is no getting around it: virtually everything early childhood administrators do in their leadership roles directly or indirectly influences their programs’ trajectories toward excellence. But administrators who take a broad view of their role understand the importance of expanding the lens, viewing leadership as an organizational asset. They see their program as a place for learning about and practicing leadership at all levels of the organization. This approach yields rich dividends for ensuring the sustainability of programs and contributing to the leadership capacity of the early childhood field.

Goffin (2013) persuasively argues that we are experiencing a defining moment for early childhood education. Over the past few decades the field has grown dramatically in both public visibility and public scrutiny. But despite important advances, early childhood education remains a field lacking in clarity about its purpose and boundaries, still largely shaped by external policy forces. Goffin exhorts a call to action, stating that leadership is needed within the field to transform it into a coherent, competent, and accountable profession. Expanding the leadership capacity of each and every program is an important step in that direction.

Tips for Expanding Leadership Capacity

Sullivan (2009) reminds us that sharing leadership often means stepping aside or stepping back to leave room for someone else to step up. Here are some steps administrators can take to expand the leadership capacity of their programs.

-

Encourage staff to take on small acts of leadership, like facilitating team meetings, leading committees or projects, contributing to the center’s newsletter, and analyzing assessment data. One director we know tapped the tech-savvy skills of millennial teachers to design a website for the center. Another supported one of the lead teachers in coordinating the center’s annual May Day family fundraiser. Short-term assignments like this allow staff to experience success, increasing their sense of their own efficacy and boosting their self-confidence so they feel comfortable accepting greater leadership responsibility in the future.

-

Craft job descriptions for roles that incorporate expanding spheres of leadership responsibility and accountability. Think about accountability as moving from managing oneself, to managing a few others, to managing a group. Having roles with expanding spheres of leadership responsibility enables staff to see pathways to growth and to contextualize their contributions to the team. During goal-setting meetings with individual staff, be sure to include a discussion of each teacher’s expanding sphere of leadership responsibility and note benchmarks in that person’s growth over time.

-

Encourage formal and informal mentoring relationships. Mentors make it safe for fledgling leaders to spread their wings and take on challenging assignments. Mentoring relationships provide mutually beneficial opportunities for individuals to grow in their leadership skills. Emerging leaders gain confidence by “checking in” with their mentors, who provide a safety net in case of major mistakes or minor miscalculations. Mentoring is an ideal leadership development activity that can build capacity in both the mentor and mentee and in the organization as a whole. Some directors implement formal teacher induction programs in which veteran teachers support new teachers during their first year on the job—a great way to foster mentoring relationships.

-

Tune in to people’s unique interests, gifts, and strengths. leadership potential often emerges from areas that people are most passionate about. A discussion about perceived strengths and interests should certainly be a part of the interviewing and selection process for new staff. In our organization, new employees complete the Clifton StrengthsFinder assessment (www.gallupstrengthscenter.com). Every year we update a matrix showing the signature strengths of all staff. We find that this is a great way to keep alive the discussion about people’s unique interests and talents.

-

Provide concrete feedback about leadership skill development. At every level of the organization, help strengthen employees’ abilities to reflect on their actions, communicate their ideas succinctly, and engage in collaborative decision making. Reflection is at the heart of honing one’s leadership ability, so providing time for reflection and candid discussions with individual staff members about growth in their leadership skills is essential for building competence and confidence. Leading a learning organization is about instilling norms of continuous improvement in which giving and receiving feedback is not a dreaded periodic activity but rather a practice that is embedded in the daily routine of living and learning together. Directors set the tone for building feedback systems that are both vertical and horizontal, with opportunities even for staff to provide feedback about their supervisor’s performance.

-

Ensure organizational structures and processes relating to meetings, schedules, and decision making promote shared leadership. Logistical procedures and organizational norms can either support distributed leadership or function as a barrier to participation. When there is clarity about protocols and procedures, people are more likely to step forward and take on greater leadership responsibility. The directors we know who are most successful in creating a culture of shared leadership are unrelenting in their effort to get as much input as possible when establishing work schedules, reviewing policies, and creating expectations for daily routines.

- Provide a forum for staff to learn about and discuss the leadership journeys of leaders in the field. Stories from early childhood leaders about their early experiences can be inspiring for those who are growing their leadership capabilities. They may identify with situations, challenges, and successes that others have experienced. Administrators can provide opportunities for staff to attend conferences and events where inspiring leaders share their stories. One director we know hosted teachers at a “dinner with an expert” event when a well-known early childhood author was presenting at an NAEYC Affiliate conference nearby.

References

Allensworth, E. 2012. “Want to Improve Teaching? Create Collaborative, Supportive Schools.” American Educator 36 (3): 30–31.

Bloom, P.J. 2014. Leadership in Action: How Effective Directors Get Things Done. 2nd ed. The Director’s Toolbox management series. Lake Forest, IL: New Horizons.

Bloom, P.J., & J. Bella. 2005. “Investment in Leadership Training—The Payoff for Early Childhood Education.” Young Children 60 (1): 32–40.

Bloom, P.J., A. Hentschel, & J. Bella. 2013. Inspiring Peak Performance: Competence, Commitment, and Collaboration. The Director’s Toolbox management series. Lake Forest, IL: New Horizons.

Bornfreund, L. 2014. “Family Engagement Is Much More Than Volunteer-ing at School.” www.edcentral.org/family-engagement-much-volunteering-school.

Branch, G.F., E.A. Hanushek, & S.G. Rivkin. 2013. “School Leaders Matter.” Education Next 13 (1): 62–69. http://educationnext.org/school-leaders-matter.

Clifford, M., E. Behrstock-Sherratt, & J. Fetters. 2012. The Ripple Effect: A Synthesis of Research on Principal Influence to Inform Performance Evaluation Design. Quality School Leadership Issue Brief. Washington, DC: American Institutes for Research. www.air.org/sites/ default/files/downloads/report/1707_The_Ripple_Effect_d8_ Online_0.pdf.

Dennis, S.E., & E. O’Connor. 2013. “Reexamining Quality in Early Child-hood Education: Exploring the Relationship Between the Organizational Climate and the Classroom.” Journal of Research in Childhood Education 27 (1): 74–92.

Eklund, N. 2009. “Sustainable Workplaces, Retainable Teachers.” Phi Delta Kappan 91 (2): 25–27.

Goffin, S.G. 2013. Early Childhood Education for a New Era: Leading for Our Profession. Early Childhood Education series. New York: Teachers College Press.

Hilado, A.V., L. Kallemeyn, & L. Phillips. 2013. “Examining Understandings of Parent Involvement in Early Childhood Programs.” Early Childhood Research and Practice 15 (2). http://ecrp.uiuc.edu/v15n2/hilado.html.

Kahn, W.A. 2005. Holding Fast: The Struggle to Create Resilient Caregiving Organizations. New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Lower, J.K., & D.J. Cassidy. 2007. “Child Care Work Environments: The Relationship With Learning Environments.” Journal of Research in Childhood Education 22 (2): 189−204.

MacNeil, A.J., D.L. Prater, & S. Busch. 2009. “The Effects of School Culture and Climate on Student Achievement.” International Journal of Leadership in Education 12 (1): 73–84.

MCECL (McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership). 2010. “Head Start Administrative Practices, Director Qualifications, and Links to Classroom Quality.” Research Notes. Wheeling, IL: National Louis University.

Muijs, D., C. Aubrey, A. Harris, & M. Briggs. 2004. “How Do They Manage? A Review of the Research on Leadership in Early Childhood.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 2 (2): 157–69.

NAEYC. 2005. NAEYC Early Childhood Program Standards and Accreditation Criteria. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Nicholson, S., & S. Reifel. 2011. “Sink or Swim: Child Care Teachers’ Per-ceptions of Entry Training Experiences.” Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education 32 (1): 5–25.

Ostroff, C., A.J. Kinicki, & R.S. Muhammad. 2013. “Organizational Culture and Climate.” Chap. 24 in Handbook of Psychology: Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 2nd ed., vol. 12, eds. N.W. Schmitt & S. Highhouse, 643–76. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Rohacek M., G.C. Adams, & E.E. Kisker. 2010. Understanding Quality in Context: Child Care Centers, Communities, Markets, and Public Policy. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute. www.urban.org/uploadedpdf/412191-understand-quality.pdf.

Skiffington, S., S. Washburn, & K. Elliott. 2011. “Instructional Coaching: Helping Preschool Teachers Reach Their Full Potential.” Young Children 66 (3): 12–19. www.naeyc.org/files/yc/file/201105/Teachers_Full_Potential_OnlineMay2011....

Sullivan, D.R.-E. 2009. Learning to Lead: Effective Leadership Skills for Teachers of Young Children. 2nd ed. St. Paul, MN: Redleaf.

Talan, T. 2010. “Distributed Leadership: Something New or Something Borrowed?” Exchange (193): 8–10.

Talan, T.N., & P.J. Bloom. 2011. Program Administration Scale: Measuring Early Childhood Leadership and Management. 2nd ed. New York: Teachers College Press.

Van Voorhis, F.L., M.F. Maier, J.L. Epstein, & C.M. Lloyd. 2013. The Impact of Family Involvement on the Education of Children Ages 3 to 8. New York: MDRC.

Wahlstrom, K.L., K.S. Louis, K. Leithwood, & S.E. Anderson. 2010. Investigating the Links to Improved Student Learning: Executive Summary of Research Findings. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Center for Applied Research and Educational Improvement.

Welch, J. 2005. Winning. New York: HarperCollins.

Whitebook, M., D. Gomby, D. Bellm, L. Sakai, & F. Kipnis. 2009. Preparing Teachers of Young Children: The Current State of Knowledge, and a Blueprint for the Future. Policy report. Berkeley: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California.

Photograph: Getty Images

Paula Jorde Bloom, PhD, is Distinguished Professor of Research and Practice and founder of the McCormick Center for Early Childhood leadership at national louis University, in Wheeling, Illinois. Paula is the author of several books and assessment tools designed to strengthen leadership and management practices.

Michael B. Abel, MA, is director of research and evaluation at the McCormick Center for Early Childhood leadership at national louis University. Mike’s background is in the area of early childhood program leadership, teacher education, and applied research. [email protected] Authors‘ Note: We wish to acknowledge the work of Matthew Clifford and his colleagues at the American Institute for Research for stimulating our thinking about the ripple effect of early childhood administrators.