Extreme Diversity in Cities: Challenges and Solutions for Programs Serving Young Children and Their Families

You are here

Cities have traditionally been centers of diversity. While urban schools may face complex challenges in providing effective education for children who speak many languages, they also have access to resources and supports not found in suburban and rural areas. Even though each city is unique, cities have a lot to learn from each other about how they support children and families from many different cultural and linguistic backgrounds, and the breadth of their experiences can be informative for nonurban communities as well.

Supporting children’s learning in their home languages is important

Although some educators may feel that because of the diversity of our cities, an English-only approach is the easiest, and possibly the fairest, approach to educating all children who are DLLs (dual language learners), in practice, this approach has been found to reduce successful outcomes for young children (Espinosa 2015). This article highlights stories about communities like Portland, Oregon, and Washington, DC, that illustrate the positive differences that can be made when attention is given to each child’s learning in their home language while they are learning English. Research has repeatedly supported this finding—supporting children as they learn in their home language is important (Nemeth 2012; Espinosa 2015). The evidence is so compelling that success depends on making every effort to provide as much home language support as possible, even though that may mean some children get more support and some get less. How those supports are implemented will change, depending on the languages of the children, the resources available, the languages of teachers and staff, the curriculum, and other factors.

New urban trends

While cities have always attracted immigrants who speak languages other than English, there are some new trends in cities impacting how schools and teachers are supporting DLLs.

Charter schools

Neighborhood schools tend to have concentrations of languages that reflect the population of that community. Many cities now have a school enrollment system that does not obligate families to attend neighborhood schools. For example, the FACT (Folk Arts–Cultural Treasures) Charter School in Philadelphia was founded by members of Asian Americans United along with the Philadelphia Folklore Project as a K–8 school to serve the diverse Chinese and Asian immigrant population of Philadelphia’s Chinatown and surrounding areas. Although the school has a strong emphasis on Chinese language and culture, it enrolls many Hispanic students as well as children from other immigrant and nonimmigrant backgrounds as neighborhood boundaries continue to soften.

Supporting new and more languages

At the same time, cities are seeing new language or cultural communities rise up very quickly. For example, Dayton, Ohio, is the only member of the Council of the Great City Schools (Uro & Barrio 2013) that  lists Turkish as one of its top five languages. This is due to the rapid growth of the city’s Ahiska Turkish community since 2011. To be successful, urban school districts must build relationships with long-standing population groups in their area while being prepared to respond to unexpected population groups or individual families as well.

lists Turkish as one of its top five languages. This is due to the rapid growth of the city’s Ahiska Turkish community since 2011. To be successful, urban school districts must build relationships with long-standing population groups in their area while being prepared to respond to unexpected population groups or individual families as well.

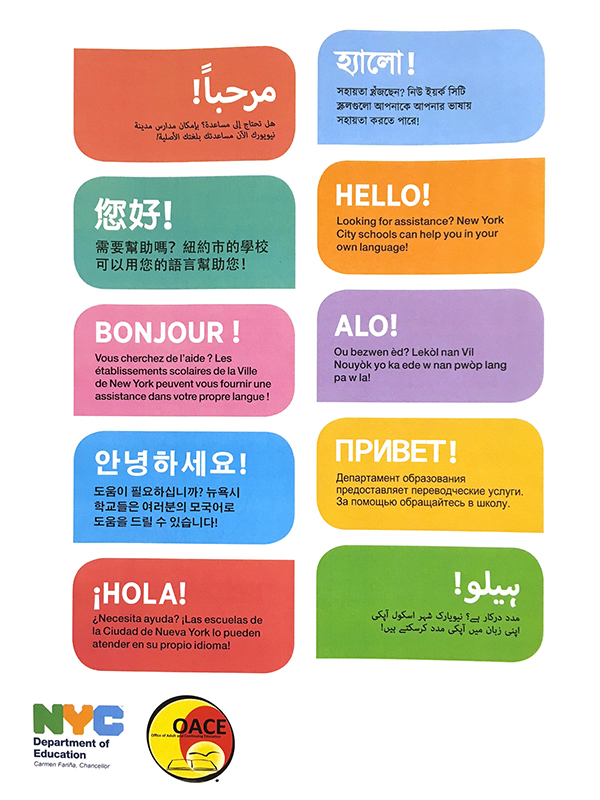

The New York City Department of Education lists more than 160 languages among its students and employees (NYC Department of Education 2016). Los Angeles reports 92 languages (LARAEC 2016) and Washington, DC, confirms over 200 languages (DC Public Schools, n.d.). These high-diversity cities often make their acceptance of diversity explicit. Many New York City school buildings post signs in multiple languages. When I visited a smaller city with a similar level of diversity, I found that the school board building and school enrollment offices had no information or signs in any language other than English. Consider the impact of these two visual approaches when new families come to enroll their children in city schools for the first time.

Common languages

High-population neighborhoods with a concentration of one ethnic, language, or cultural group place extensive demands on a school district to meet their particular needs. In some cities, there can be hundreds or thousands of children speaking a particular non-English language. This may be Spanish—but in some cities that language might be Chinese, Tagalog, Vietnamese, or Somali. These concentrated communities also provide unique opportunities to recruit teachers, paraprofessionals, and volunteers who connect well with students from the same community.

Businesses in a neighborhood may be ready and willing to support the school’s particular population with funds, supplies, advocacy, and bilingual volunteers. A concentrated population means there may be social and cultural organizations and communities of faith that are strongly connected and willing to help. Some city schools are masterful in their ability to build strong community relationships that help them meet the needs of diverse young children and their families. Others have not yet taken advantage of these opportunities but will find many ideas in their community they can replicate.

Many Latino families in the New York/New Jersey area are from the Puebla area of Mexico, and many of them have settled in Passaic, New Jersey. The government of Puebla recently established an agency, Mi Casa es Puebla, with offices in Passaic. The staff have built a mutually beneficial relationship with the nearby Head Start program, and are building connections in the local community, sharing meeting space, and distributing Mexican learning materials and programs.

Rare languages

A different challenge occurs in urban areas when there are so many different languages that it is not possible to find appropriate books and materials for each and every language. Take another look at the hello sign from New York. It is impressive to see a sign with so many languages represented, but when you consider that the district actually has more than 180 languages, you realize how many students are left out of these efforts. Urban areas attract clusters of immigrants from certain countries, but they also attract immigrant families from small countries who speak rare languages. A small district might encounter one or two children who speak a low-incidence language, but in some cities there can be one or two children from each of 20 languages or more. The concern is that educators and administrators see how much work and money is going into supporting the high-concentration languages and may feel they have things covered, when the reality is that many children are still left out. When asked by a state or national survey whether they provide early learning supports for dual language learners, they can accurately say yes, but they are doing a lot for some and nothing for others.

Partnering with diverse families

Whether you work in a big city or a small town, partnerships with families are certainly important to your work in early childhood education. Urban programs with lots of diverse families need lots of resources to help them become fully engaged. When many families are bilingual, programs can provide resources by forming a core group of ambassadors to welcome and support newcomer families and to help a diverse school run more smoothly.

One teacher in the Living for the Young Family Through Education (LYFE) program in New York City involved families in the classroom by inviting young mothers to bring traditional dishes from their home countries to school for the toddlers. Using invitations, picture signs, and word of mouth, the teacher got all of the parents involved. The families in this small class were from different countries, some speaking rare languages such as the Senegalese Mandinka language. They filled the classroom with language, stories, and food—some even wore traditional garb. The teacher took photos to make a class book. Photo captions were later translated, with the help of family members, to represent every language used in the classroom.

In cities with larger groups of families who share a language or cultural background, the families may gather together to form a stronger voice with which to influence practices and policies in your program. Successful parent engagement, especially with large groups of vocal families, depends on navigating these interactions with respect and openness. Professional development can help staff become more effective in their work with diverse families and help to reduce burnout (Vesely & Ginsburg 2011). An advantage of urban locations is that early childhood programs are close together and can join forces to address community needs and to share professional development events and resources as they work to build family engagement throughout their communities. According to the Council of the Great City Schools report (Uro & Barrio 2013), most of their member schools reported using Title III funding for parent engagement activities.

Partnering with communities

Most city neighborhoods have libraries. Some successful, diverse programs partner with librarians to order books and materials in each language needed for their classrooms. Introducing families to the local library is another good way to build family engagement across languages and cultural differences. Your program could uphold developmentally appropriate practice by building its own language resource library filled with materials families have contributed or made, purchased books and materials that have been translated into different languages by the families, and culturally appropriate props, such as cooking utensils, decorations, musical instruments, clothing, and sports equipment.

Another advantage of urban settings is the availability of foundations and funders that focus on initiatives to help the city or who work specifically to support particular population groups that come to your program. A great place to start building these relationships is to make a connection with your local United Way or community-based charity organization.

Examples from cities across the United States

The preschool program run by the Camden, New Jersey, school district established model bilingual classrooms to help early childhood teachers be more effective with diverse young children. Cities like New York and Washington, DC, are responding to increasing demand for dual language immersion classes by expanding their offerings to more grades and more locations, and adding languages to the plan, such as English/Arabic or English/Mandarin. In an unprecedented move, the Clark County school district

that includes Las Vegas added days to the school year by establishing the Zoom Schools program to address achievement gaps for dual language learners in the early grades (Clark County School District 2014). Funded by the state, the program added additional school days for at-risk children, curriculum resources, professional development for teachers, universal preschool, full-day kindergarten, and enhanced family engagement programs. Immediate results were seen in closing the score gaps on the district’s preschool assessment of literacy and math learning.

Leaders of Portland, Oregon’s David Douglas school district recognized that they were not providing effective services for the district’s large and growing population of dual language learners. They brought together multiple stakeholders and blended a variety of public and private funding sources to plan and implement improvements in their schools. By combining the resources available to a city school district, David Douglas leaders were able to create an extremely comprehensive plan and set up the system-wide changes needed to accomplish it properly. With changes in their instructional model to bring a clear focus on oral language development, professional development for teachers, and expanded family engagement strategies, measurable improvements were achieved. This underperforming, high-needs urban district had student outcomes that rose to meet state benchmarks once the changes were put into place (Williams & Garcia 2015).

Strategies that work in diverse urban settings

Many programs hire bilingual paraprofessionals to meet the diverse and changing language needs of children in their programs. These positions have lower salaries and fewer requirements than teachers, so districts and preschools find it easier to add them to staff rosters. To make this strategy work, orientation and professional development supports are critical. Reaching out to families and community members to find and hire teaching assistants who speak the children’s languages is a great idea, but the assistants need to know how and when to use those languages in the early childhood classroom according to the policies and curriculum of the particular program (Nemeth 2012).

Some cities are also taking an aggressive approach to recruiting bilingual teachers. For example, we see city school districts hosting vendor booths designed to attract bilingual teacher candidates at bilingual education conferences outside of their own states. Many cities are also working more closely with colleges and universities to ensure that qualified teacher candidates represent the backgrounds and skills needed in the school district (Uro & Barrio 2013). Some districts, such as those in Chicago and Philadelphia, have rushed to require or recommend that early childhood teachers return to college to obtain ESL (English as a second language) endorsements to their teaching certificates. For this policy to work, most ESL programs at colleges need to update their courses to include content addressing the particular needs of young language learners. Changes in professional development and preparation of teachers is a necessary piece of this effort to ensure success.

Diverse early childhood programs need books, manipulatives, pretend play materials, and displays that reflect the languages and cultures of the children. Urban centers have access to a wealth of possibilities to meet these needs, but city districts should coordinate resources to ensure that all programs, large and small, have access to these needed supports. One key component for success that cities can offer is Internet access. Digital and online resources allow programs to respond to many languages and cultures by providing options for book translations, links to cultural information, and learning activities open to different languages.

Looking toward an increasingly diverse future

Urban early childhood programs face many challenges as the diversity of our population of young learners continues to grow. Their efforts to include and celebrate that diversity can serve as inspiration for all early childhood educators. As programs work to weave together the threads of different languages and cultures into a tapestry of success for young children, they strengthen their ability to meet the needs of each individual child. That is truly the goal of developmentally appropriate practice for our entire field.

References

Clark County (Nevada) School District. 2014. “Zoom Schools and a Focus on English Language Learners.” Just the Facts. http://promotion.ccsd.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/JTF-Zoom-Schools-12....

District of Columbia (DC) Public Schools. n.d. “English Language Learner (ELL) Support.” http://dcps.dc.gov/service/englishlanguage-learner-ell-support.

Espinosa, L.M. 2015. “Challenges and Benefits of Early Bilingualism in the Unites States’ Context.” Global Education Review 2 (1): 14–31.

LARAEC (Los Angeles Regional Adult Education Consortium). 2016. “Los Angeles Unified School District.” http://laraec.net/los-angeles-unified-school-district.

Nemeth, K.N. 2012. Basics of Supporting Dual Language Learners: An Introduction for Educators of Children From Birth Through Age 8. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

New York City (NYC) Department of Education. 2016. “Office of English Language Learners 2013 Demographic Report.” http://schools.nyc.gov/NR/rdonlyres/FD5EB945-5C27-44F8-BE4B-E4C65D7176F8....

Uro, G., & A. Barrio. 2013. English Language Learners in America’s Great City Schools: Demographics, Achievement, and Staffing. Washington, DC: Council of the Great City Schools.

Vesely, C.K., & M.R. Ginsburg. 2011. “Strategies and Practices for Working With Immigrant Families in Early Education Programs.” Young Children 66 (1): 84–89.

Williams, C.P., & A. Garcia. 2015. A Voice for All: Oregon’s David Douglas School District Builds a Better PreK–3rd Grade System for Dual Language Learners. Washington, DC: New America Foundation.

Photographs: 1, © iStock; 2, courtesy of the author

Karen Nemeth, EdM, is an author, speaker, and consultant on early childhood language development at Language Castle LLC. She is the author of Basics of Supporting Dual Language Learners: An Introduction for Educators of Children From Birth Through Age 8. [email protected]