Engaging Teachers and Toddlers in Science (Voices)

You are here

Thoughts on the Article | Barbara Henderson and Frances Rust, Voices Executive Editors

Site director Talene Artinian’s study is remarkable for its twin focus on engagement in science by very young children, specifically 2-year-olds, and on collaboration among teachers and administrators to shape these science experiences. Over the years, Voices of Practitioners has published a number of articles that inform us about the capacity of very young children to engage with complex concepts that help them understand the world. Yet it is rare to have a study that so beautifully captures the equally complex issues of sharing power and taking responsibility for the curriculum that teachers and administrators face as they shape learning experiences for children—especially in a content area where some of them feel insecure about their knowledge. A finding by Artinian that will echo for many of us in early childhood was how strongly the teachers originally believed that science was just “too hard” for young children to grasp. One measure of this project’s success was how the teachers adjusted these attitudes as they became a part of the children’s wonderment.

As Talene and her teachers continue to engage in inquiry, they could provide more open-ended discovery and exploration. Since Talene was inspired to undertake this unit on solids and liquids by a heavy winter snowfall, the teachers could have used the same real-world provocation to engage the children, for example, bringing in snow and icicles to watch them melt in the warmth of the classroom, and setting colored water outside to freeze instead of using the freezer. Outside during play, they could have encouraged the children to look for patches of ice and places where the snow was melting, and then see what actions they could take to change the state of matter—holding a bit of snow in their hands, putting rock salt on an icy patch, chopping at a piece of ice and then setting a chunk of it in a sunny patch on the yard. Teachers become more confident with science content the more they see that it is all around us; it is, in some ways, “simple,” as one of the teachers said with some relief near the end of the project.

An inquiry extension for Talene and the teachers might be for them to trace how their knowledge base and experiences serve as entry points and potential barriers to developing high-quality inquiry for children. Talene’s educational background as a science major and her use of the Pennsylvania state standards for additional guidance helped her feel certain that she could launch this curriculum. Looking ahead, she might examine how her focus on literacy-oriented experiences, such as reading books, making painted marks with colored water from melted ice, and learning vocabulary, is just part of the science experience. For the teachers, their inquiry might lead them to see a connection between what they had been experiencing as behavior challenges and the positive effects of the richer, more child-centered curriculum they were able to enact with Talene’s support.

Through support and collaboration, Talene provided a new curriculum and an overall experience of science inquiry that positively affected the attitudes of the teachers and the experiences of the children. Although a key goal of Voices of Practitioners is to amplify the voices of teachers as researchers, we (as founders of the journal) were very deliberate in choosing the word practitioners to emphasize the ecosystem of professionals who make early childhood education work. Talene’s experience is an example of an initial foray into teacher inquiry at a school site. Her leadership was powerful because she included the teachers as coparticipants, while also demonstrating a willingness to model lessons and new ways of interacting with the children in the classroom. Talene’s reflections as a leader supporting teachers to engage in inquiry provides a crucial model, as teacher research is most likely to flourish in a community and when teachers feel they have sufficient structural supports to succeed. Thus, Talene’s article helps us as a field to refocus on the fact that for children to be engaged productively and comprehensively in inquiry, practitioner research must be an ongoing goal for all of us—teachers, administrators, and university faculty.

Teaching has always been my passion—especially teaching science to young children. Having a bachelor’s degree in science and 12 years of experience educating young children, I recognize and support young children’s natural propensity to investigate everything around them. Researchers have long noted children’s drive to explore and understand, finding that even the very youngest children are inquiring, theorizing, and making sense of the world (Gopnik, Meltzoff, & Kuhl 1999) and that inquiry begins in the crib and continues throughout life—as long as it is nurtured (National Research Council 2000). Even very young children have strong cognitive abilities and can, to a certain extent, reason scientifically (Willingham 2007).

Teaching has always been my passion—especially teaching science to young children. Having a bachelor’s degree in science and 12 years of experience educating young children, I recognize and support young children’s natural propensity to investigate everything around them. Researchers have long noted children’s drive to explore and understand, finding that even the very youngest children are inquiring, theorizing, and making sense of the world (Gopnik, Meltzoff, & Kuhl 1999) and that inquiry begins in the crib and continues throughout life—as long as it is nurtured (National Research Council 2000). Even very young children have strong cognitive abilities and can, to a certain extent, reason scientifically (Willingham 2007).

As site director and a lead teacher at a center for infant and toddler education and care, one of my goals is to ensure that all of the children engage in scientific explorations. One challenge I have faced is finding ways to support teachers so they can effectively foster science learning in the classroom (Gerde, Schachter, & Wasik 2013). Through my observations, I realized that teachers did not seem to recognize the science learning opportunities that were embedded in their activities. For instance, when children collected leaves to make art, the teachers did not include opportunities for children to explore related science concepts, such as learning through read-alouds how trees change, depending on the season. I began to wonder, How can my fellow teachers and I better facilitate children’s inquiry and promote natural scientific curiosity?

Our center is NAEYC accredited, state licensed, and rated four out of four on the state rating system. It provides a high-quality early learning program that strives to meet the social, emotional, and cognitive needs of each child. We follow the Pennsylvania Early Learning Standards for Early Childhood: Infants–Toddlers (Office of Child Development and Early Learning 2014) and the Creative Curriculum for Infants, Toddlers, and Twos (Teaching Strategies 2013), which provides a curriculum framework for teachers. However, neither of these guides offers specific lesson plans for children under age 3. While there is a lot of published literature on the effect of science learning in the classroom, I found little that addresses implementing a science curriculum designed for 2-year-olds.

The most relevant guidance I found came from the Pennsylvania Early Learning Standards for Early Childhood: Infants–Toddlers (Office of Child Development and Early Learning 2014). While these standards offered a solid foundation for beginning to understand biological, physical, and earth sciences, the content and suggested activities were too vague to support the rich science instruction I hoped to cultivate. For example, one of the biological sciences standards for young toddlers states, “Explore the basic needs of plants and animals. . . . The adult will . . . provide indoor and outdoor experiences that include safe interaction with animals, plants, and other people” (56, standard 3.1.YT.A.2). The teachers at my center were not confident that they knew which “experiences” were appropriate.

Similarly, another standard suggests that young toddlers should “participate in simple investigations to observe living and non-living things . . . use senses and simple equipment to explore . . . engage with adult provided materials . . . and use outdoor time . . . to explore and investigate the environment” (58, standard 3.1.YT.A.9). While helpful for thinking broadly about a curriculum for our toddlers, these standards are not specific enough to meet our needs; they do not provide a curricular focus or show teachers how to support science learning or recognize the science aspects of their teaching.

Undaunted, I turned to two teachers of toddlers at the center and asked if they would be interested in working with me to develop and implement a science curriculum for our program. Both said that they were horrible at science when they were younger, so they felt overwhelmed by the idea of teaching science. In addition, they considered science too difficult a subject for their age group. When I explored the idea with our center’s community, some parents also questioned the notion that 2-year-olds could engage in science.

Balancing my interest in science with the teachers’ skepticism and discomfort, I decided to undertake this work as an action research study. Stepping back from my initial assumption that we could succeed in developing our own science curriculum, I asked: What happens when teachers and their director collaborate to engage very young children in science experiences?

Action research

Our center has three distinct age groupings: 0 to 12 months, 13 to 24 months, and 25 to 36 months. After discussing options with teachers, I decided to focus my inquiry on the implementation of science- and nature-based experiences in the 2-year-old classroom of 10 children, taught by Karen and Tiffany. Karen had an associate’s degree in early childhood education and eight years of teaching experience. Tiffany was completing her bachelor’s degree in early childhood and had two years of classroom experience. (Both teachers agreed to participate in the study and signed an agreement that their participation would not affect their employment or evaluation.)

The teachers were concerned about their class, feeling that the children were not working together as well as they should be since it was early spring and the group had been together for several months. In the beginning, Karen and Tiffany welcomed working with me on this study mainly because they hoped that through my more frequent presence in the classroom, they would learn new ways to shift the children’s dynamic. Still, they were anxious about teaching science.

We agreed that I would design the science lessons, we would review the content and activities together in advance, and then they would coteach the lessons with me. We reached out to families to let them know that we would be introducing a science curriculum. Per our regular school practices, we committed to keeping families updated on daily activities by email.

Over the six weeks of our science study, I observed both the children and the teachers for two hours each day, while recording notes and taking photos or videos. I taught most of the science lessons at the beginning of the project; approximately three weeks later I moved into a support role. In order to understand the teachers’ experiences, goals, and attitudes toward science education, I administered pre- and post-surveys and conducted interviews with the teachers at the beginning, midpoint, and end of the study. I also kept a journal in which I recorded observations and reflections about what I was seeing and learning.

Science activities in the toddler classroom

We developed a six-week science unit for children in the toddler classroom. Our planning began in early March. Given the great deal of snow that had fallen in the last two months, it seemed appropriate to think about freezing and melting. After considering the background knowledge the children would need to investigate those concepts with a scientific lens, we decided to spend the first three weeks on solids and liquids and then focus the final three weeks on freezing and melting.

In my initial planning, I had wanted to address the teachers’ concerns about the complexity of scientific concepts and what 2-year-olds should be expected to understand. I consulted Pennsylvania Learning Standards for Early Childhood: Infants–Toddlers to make sure our activities and the materials we chose were age appropriate, and I thought about the language the children could learn through our guided science play. Karen, Tiffany, and I committed to consistently using—and listening for the children’s use of—the words solid, liquid, hard, cold, warm, freezing, melting, ice, and water. We hoped that the children would find the activities exciting and that their ability to play and work together would improve as we facilitated science exploration. Personally, I hoped that the children’s excitement would become infectious, helping Karen and Tiffany relax and perhaps even enjoy teaching science as they shared in the children’s enthusiasm.

During the first three weeks, the children learned about solids and liquids from books read by their teachers and from audio materials that were part of the general classroom equipment. They explored ice cubes, colored water, items from the play area, and their lunch foods. They examined different containers and materials to determine whether liquids (e.g., water with food coloring) and solids (e.g., crayons) would change shape.

In the final three weeks, children investigated freezing and melting by enjoying more read-alouds and participating in activities such as painting with “brushes” made of popsicle sticks in ice cubes to observe melting. Children also examined colored ice cubes in different environments to observe the effects of temperature on them.

During each science activity, teachers asked a range of questions to promote children’s understanding and encourage inquiry. Karen and Tiffany often asked questions like “What do you see?,” “How does it feel?,” “Is it a liquid?,” “Is it a solid?,” “What is happening to the ice?,” and “What is happening to the water?”

The teachers’ perspectives

At three points during the unit, I interviewed Karen and Tiffany about what they were seeing and hearing. In the beginning Tiffany felt that for this age group science “may be too hard for them to comprehend.” Karen likewise thought that “incorporating science would be really great, but the children are too young.” A week after starting the unit, Karen commented, “I have seen the children really excited and happy to learn. Just the other day, I heard the children looking for solids on their own in the classroom, without prompting.” Midway through the study Tiffany said, “The children are so excited. I actually am amazed how some of the more quiet children are involved and engaged.” Karen noted, “I can see how fast the children are learning and how excited they are. They seem to be working better together as well.”

It seemed that the children’s enthusiasm engaged the teachers more wholeheartedly in the science curriculum. For example, Tiffany reported, “I am having a lot of fun doing science with the children; I love watching their faces light up when we do something cool with science.” Karen stated, “At first I could not think of many science projects, but now I find myself thinking about it all of the time.” At the end of our science unit, Tiffany commented, “It was great to watch the children have fun with science, which I initially thought was too hard for their age.” She added, “I always thought science was really important for all ages. I just was not sure how to introduce it to children this young. I now understand more how simple and fun science is.” Karen said, “I think these past six weeks have been amazing. I have learned as much as the children did.”

The teachers’ comments were heartening, and their growth in facilitating science learning became clear halfway through our unit—they themselves developed a science lesson based on planting flowers. Their idea extended our exploration of solids and liquids—using flowers and the soil as solids and water as the liquid—to move children toward the deep concept of living things.

What we learned about teaching science to toddlers

To those who spend time with young children and see their sense of wonder about the world, what we learned should come as no surprise: Children are natural scientists! However, we do have some useful insights into creating an environment that bolsters their natural inquiry.

The teachers and I began from a place of insecurity. The teachers seemed uncomfortable with science and were unaware of how to include the subject in their work with young children. I did not know how to change the environment in ways that would support the teachers so they could support the children. I knew that if we could incorporate science into the daily life of the classroom in relevant, meaningful ways, we could spark children’s curiosity and accomplish the essential early science goal of helping children learn about the world that surrounds them (Tsunghui 2006).

Our choice of liquids and solids—including the illustration of changing states of matter through making and melting ice cubes—was grounded in what we believed the children could experience at home as well as in school. If our project was successful, we would see and hear the children incorporate our target science vocabulary into their daily talk; we would also discern through their actions and interactions a growing understanding of the concept of matter—specifically, solids and liquids. In addition, we thought these group investigations would help the children work more collaboratively together. We hoped to hear children asking questions and engaging in problem solving (Hamlin & Wisneski 2012)—even children as young as 2. In both cases, we were not disappointed.

We were heartened by how much fun it was to work together and how the children’s excitement sparked our own. Karen and Tiffany have continued to develop and implement science activities for the children. They now take time to independently research different science topics and activities and then incorporate those activities into our curriculum. So far, they have explored surface tension, inclines, and volcanoes.

Early childhood education scholars have described three goals for children’s active science learning (Seefeldt & Galper 2007):

- To develop each child’s innate curiosity about the world around him

- To broaden each child’s thinking skills for investigating the world, solving problems, and making decisions

- To increase each child’s knowledge of the surrounding natural world

In our small action research study, we saw that these goals are completely appropriate—even for 2-year-olds. We learned a number of lessons from this project—the importance of giving children time and room to experiment, of priming their attention with carefully chosen books and carefully crafted activities, of listening and encouraging their talk—and we have tried to apply them more fully into our work with the children.

As role models for the children, our learning, like theirs, required that we be more hands-on. For me, as a director, the lesson plans were all about curiosity, play, and scaffolding. This research experience taught me how to shift from feeling like I must lead at all times to encouraging the teachers’ exploration and independence. After modeling for the teachers, I was able to step back so they could see their impact and appreciate the children’s exploration and questioning.

Our next steps are to find ways to integrate scientific exploration, reflection, and question development more fully into the toddler classroom, knowing that integrating science experiences with other curriculum areas—such as math, music, literature, art, and creative thinking—can improve children’s learning and development (Gerde, Schachter, & Wasik 2013). The tools of inquiry that I used to monitor progress need to become the tools helping us nurture the scientists in our midst—both children and adults. Implementing science in the classroom has reminded me how rewarding our role as teachers is and how much we can enjoy each moment.

A View from the Inside: Selected Observations

Because I served as both a coteacher and the researcher, the bulk of my data is in the form of notes written as soon as possible after a lesson or activity, and journal entries written later in the day. The following observations range from our introduction of solids and liquids to our final experiment with ice cubes in different environments.

Today we read a story called Solids and Liquids, by David Glover. The children and teachers appeared to be engaged and interested. I asked the children questions about pictures they saw in the book and whether each was a solid or liquid. Most of the children responded with the correct answer. After the story, we painted using solids (paintbrush and paper) and liquids (different colors of paint) and discussed the differences between the solids and the liquids used in the painting activity. We then went on a discovery hunt in the classroom to find solids. They collected binoculars, a plate, plastic animals, a truck, a puzzle piece, and a doll from various learning centers. Teachers gathered children around the classroom table to examine, feel, and discuss each item. When asked, children were able to categorize the items correctly as liquids or solids. Parents received a description of what was learned and suggestions to try at home.

The following day, children began to express in more detail the differences between solids and liquids:

When we read Solids and Liquids for a second time, the children were more engaged and understood much more. Some of them said, “Ms. Talene, look, my sock” or “My shirt” when we were discussing solids.

Halfway through the unit, as we added freezing and melting to our exploration of solids and liquids, the children’s use of our target vocabulary increased and the day demonstrated growing understanding of the initial concepts:

Today, I brought ice cubes to circle time for children to explore. I had each child feel the ice cube and describe what they felt. Some responded by saying it was “cold,” “hard,” “slimy, “slippery.” They were able to identify that the ice cube was a solid. I then had them observe the change from solid to liquid. When asked what was happening to the ice cube, the children responded “melting,” “water,” “oh no,” “spilling, Ms. Talene.” I explained that the solid ice cube changed into a liquid. I could see that the children were amazed, based on the reactions on their faces and their attention to our activity.

A week later, the children were enthusiastically learning and playing with ice:

We read Freezing and Melting by Robin Nelson. We used water and food coloring to explore melting and freezing. The children helped pour water into the ice trays and we added a drop of red food coloring into each slot. We then placed the tray into the freezer. When asked how the freezer felt, children responded, “It is cold, Miss Talene,” “It is freezing—I need my jacket!” After naptime, we gathered the ice cube trays and observed that they were partially frozen. The children added the popsicle sticks to create ice paint brushes. The children used words such as cold, freezing, ice, red, slushy, mushy, and wet to describe the freezing mixture.

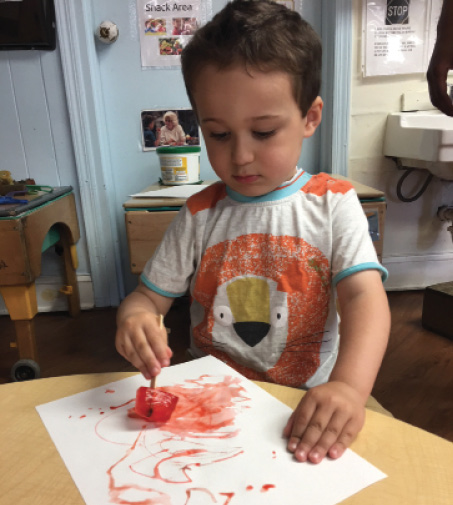

Later in the day, the children were amazed to find that their colored water had frozen. The children used their popsicle stick ice cubes to paint on white paper. As they painted, we observed the ice cubes melting. The children were excited to tell their teachers about ice. “Miss Talene, ice cubes are cold,” “Ms. Karen, the ice cubes are freezing.”

In my researcher’s journal, I made the following observation:

The children’s vocabulary has improved. They are making language connections using words such as slimy, slippery, wet, melting, hard, and soft. They were able to find many solids and liquids during their discovery hunt. We discussed how water takes the shape of its container and how the solids do not.

Reviewing my notes, what stands out is how the teachers and children inspired each other. As our teachers showed interest in science, children became more involved. Similarly, seeing the children’s enthusiasm, teachers became more motivated, and their self-confidence in teaching science grew.

References

Gerde, H.K., R.E. Schachter, & B.A. Wasik. 2013. “Using the Scientific Method to Guide Learning: An Integrated Approach to Early Childhood Curriculum.” Early Childhood Education Journal 41 (5): 315–23.

Gopnik, A., A.N. Meltzoff, & P.K. Kuhl. 1999. The Scientist in the Crib: What Early Learning Tells Us about the Mind. New York: William Morrow.

Hamlin, M., & D.B. Wisneski. 2012. “Supporting the Scientific Thinking and Inquiry of Toddlers and Preschoolers through Play.” Young Children 67 (3): 82–88.

National Research Council. 2000. How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School. Expanded ed. Washington, DC: The National Academy Press.

Office of Child Development and Early Learning, Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, & Pennsylvania Department of Education. 2014. Pennsylvania Learning Standards for Early Childhood: Infants–Toddlers. www.pakeys.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/2014-Pennsylvania-Learning-Sta....

Seefeldt, C., & A. Galper. 2007. “Professional Development: ‘Sciencing’ and Young Children.” Scholastic. www.scholastic.com/teachers/articles/teaching-content/professional-devel....

Teaching Strategies. 2013. The Creative Curriculum® for Infants, Toddlers & Twos. 3rd ed. Bethesda, MD: Teaching Strategies.

Tsunghui, T. 2006. “Preschool Science Environment: What Is Available in a Preschool Classroom?” Early Childhood Education Journal 33 (4): 245–51.

Willingham, D.T. 2007. “Critical Thinking: Why Is It So Hard to Teach?” American Educator Summer: 8–19. www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Crit_Thinking.pdf.

Voices of Practitioners: Teacher Research in Early Childhood Education is NAEYC’s online journal devoted to teacher research. Visit NAEYC.org/resources/pubs/vop to peruse an archive of Voices articles.

Photographs courtesy of the author

Talene Artinian, MED, is site director and a lead teacher at Delco Early Learning Centers in Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania.