What Babies Ask of Us: Contexts to Support Learning about Self and Other

You are here

Observing and listening with care is where infant and toddler teaching and learning begins. At the 2011 NAEYC conference, Vivian Gussin Paley (2011), noted educator and advocate for the power of listening to children’s stories, began her talk with these words, “Two questions predominate in the minds of young children: ‘Where’s my family?’ and ‘Who’s my friend?’” In few words, Paley, author of thirteen insightful books that illuminate children’s social and emotional competence, captured the essence of what young children ask of us with respect to social and emotional support.

Throughout her long career in early childhood education, Paley listened with great care to children as they played. In return, they revealed to her their quest to make sense of strong feelings and to make friends. This echoes the teaching of other wise early childhood educators. Carlina Rinaldi, president of Reggio Children and professor of pedagogy at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, advises, “The most important verbs in educational practice are no longer ‘to talk,’ ‘to explain’ or ‘to transmit’—but ‘to listen’” (2006b). And Magda Gerber, the inspirational founder of Resources for Infant Educators, suggests, “Let go of all other issues that wander through your mind and really pay attention. . . . Infants do not yet speak our language but they give us many, many signs” (2002, 6).

Infant and toddler teaching and learning starts with observing and listening with care. Throughout the day, infants strive to make meaning of strong feelings:

- the tender moments of sadness when family members depart, leaving them behind

- the unsettling conflicts spawned as one toddler lashes out in anger when another grabs away a toy

- the silent, curious dialogue that transpires as two 12-month-olds sit near each other, one watching the other explore a toy

- the look of excitement and anticipation on a baby’s face in a game of peek-a-boo

Infants Are Highly Aware of Others

Researchers who seek to understand how infants and toddlers develop socially and emotionally carefully listen to and observe them. What they have discovered about how infants “know” others is fascinating (Reddy 2008). An infant just a few hours old, when held face-to-face, will imitate a researcher’s facial gesture, such as a protruding tongue (Meltzoff & Moore 1983). Researchers also found that when they showed infants scenes with puppets—in which some puppets act in ways that help others and some act in ways that hinder others—infants distinguished between behavior that helps and behavior that hurts (Hamlin, Wynn, & Bloom 2010; Hamlin et al. 2011). For example, infants 5- to 12- months-old were shown a scene in which a puppet tries but fails to open a box. In the next scene, a different puppet pops up and helps the first puppet open the box. The babies were shown the original scene again, but this time a third puppet pops up and flops down hard on top of the box, preventing the box from being opened. When researchers showed the infants a tray holding a choice of two puppets (the puppet that helped and the puppet that hindered), overwhelmingly, they chose the puppet that helped (Hamlin & Wynn 2012).

In another series of experiments, researchers observed that when toddlers watched someone who appeared to need help, they often tried to assist them (Warneken & Tomasello 2007). For example, when toddlers watched as a researcher silently struggled with the simple task of opening a cabinet door while balancing a stack of books, most toddlers moved to assist within ten seconds, walking to the cabinet and opening the door. In another study, toddlers watched as a researcher pinned clothes on a clothesline. The researcher accidentally dropped a clothespin, and although the researcher made no request for help, most of the 18-month-olds retrieved and returned the clothespin to the researcher. However, when the researcher intentionally threw the clothespin to the floor as the toddler watched, the toddler did not retrieve the thrown object.

These investigations are part of a growing body of research detailing babies’ emerging understanding of others’ feelings and intentions. Key findings demonstrate that infants

- are biologically prepared to seek out and interact joyfully with companions (Trevarthen & Bjorkvold 2016)

- expect social partners to respond in kind to their gaze, smile, or vocalization (Markova & Legerstee 2006)

- appear to assess people’s actions and vocalizations as safety or threat, helpful or hurtful (Warneken & Tomasello 2007; Rapacholi et al. 2014)

This image of infants as highly aware of others’ intentions and feelings challenges a long-held assumption that children under 3 are “egocentric,” meaning that they have difficulty seeing others’ perspectives or needs. In fact, more recent evidence suggests the opposite—infants are more inclined to be “allocentric,” meaning that they are biologically prepared to be aware of and concerned with others’ movements, orientation, and feelings, and they are eager to engage with and imitate others (Trevarthen & Delafield-Butt 2017). In short, infants come into the world actively making meaning of people.

The Three Contexts for Learning

In social play and interaction with others, infants learn the conventions, skills, and concepts valued in the culture that surrounds them (Rogoff 2003). As active makers of meaning, infants ask those who care for them to respect their competence and to support their efforts to engage with others and to cope with strong feelings that often emerge as they do so. As Rinaldi explains: “Children ask us to see them as scientists or philosophers searching to understand something, to draw out a meaning. . . . We are asked to be the child’s traveling companion in this search for meaning” (2006a, 21).

J. Ronald Lally, who served as the co-director of the WestEd Center for Child and Family Studies, builds on Rinaldi’s sage advice when he writes, “The most critical curriculum components are no longer seen as lessons and lesson plans but rather the planning of settings and experiences that allow learning to take place” (2009, 52). When caring for a group of infants, there are three such settings, or contexts for learning (Maguire-Fong 2020). One context is the play space, thoughtfully prepared and provisioned to support the inquisitive infant or toddler. A second context involves the daily routines of care, like diapering, meals, dressing, and preparing for nap. Each routine is an excellent opportunity to invite infants and toddlers to use emerging skills and concepts. The third context occurs within the everyday conversations and interactions, like the stories and songs we share with young children or the guidance we offer with respect to their behavior.

Play Space as a Context for Learning about Self and Other

Infants’ social play with peers begins simply—an infant offering a book to another infant, or a shake of the head and a laugh while watching another infant shake her head and smile. This early play grows into shared imitation of familiar experiences. For example, one infant holds an empty cup near another infant, who pretends to drink from the cup. Such peer play emerges spontaneously.

A month into the new school year, Vickie Leahy and Jodie Gabriel, coteachers at the San Diego Cooperative Preschool, notice how 13-month-old Stella and 14-month-old Elena often play alongside each other, each pursuing her own play but doing so near the other. One hides behind a curtain, and within minutes, the other follows. If one goes to the other side of the yard, within minutes, so does the other. The teachers also witness an interest and curiosity in what another is doing in infants a few months younger—crawlers Emilio and Greta. Vickie photographs a long sequence in which Emilio plays with a metal spice tin while Greta watches. Soon, Emilio reaches toward Greta, spice tin in hand, and waits. After a pause, Greta takes it and shakes it up and down. Emilio watches, reaches toward Greta, waits, but Greta continues to shake the tin up and down. Reaching to her with open palm, Emilio looks intently at Greta, but then he spies a feather on the ground, picks it up, holds it out toward Greta, and waits, watching her expectantly.

Are the teachers witnessing the blossoming of friendships? Although playing independently, each child remains aware of what the other is doing. With Emilio and Greta, there appears to be an experiment in give and take, a first encounter with sharing, a simple negotiation.

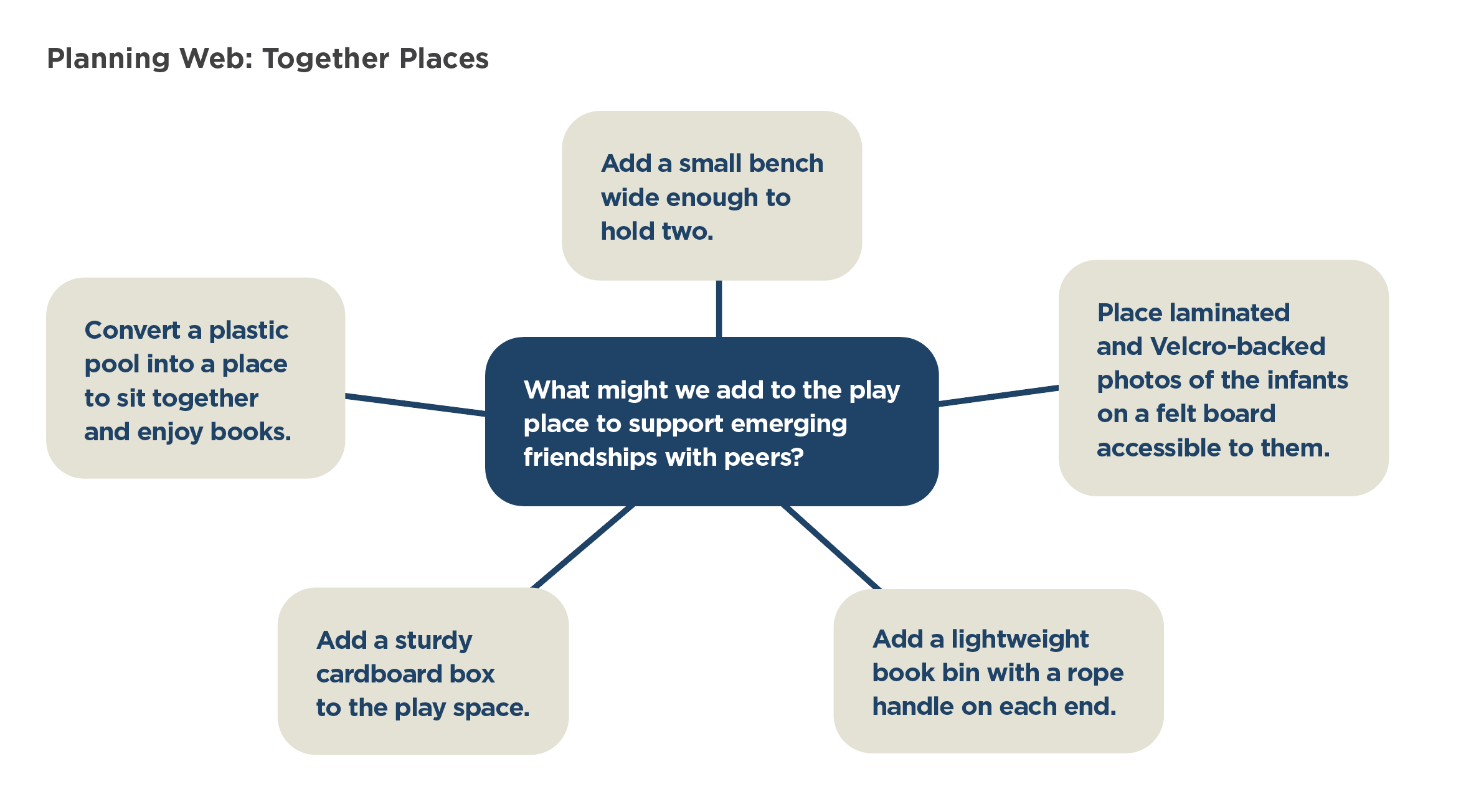

These observations and interpretations prompt this question, “What might the teachers add to the infants’ play space to support emerging friendships with peers?” A planning web is a simple way to hold possible ideas (see “Planning Web: Together Places” below). By sifting through the proposed ideas, teachers can decide what to offer next in support of infants’ learning.

Reprinted by permission of the Publisher. From Mary Jane Maguire-Fong, Teaching and Learning with Infants and Toddlers: Where Meaning-Making Begins, 2nd Edition. New York: Teachers College Press. Copyright © 2020 by Mary Jane Maguire-Fong. All rights reserved.

After exploring ideas of what they might add to the play space to support peer play, teachers Vicki and Jodie added a sturdy, wide cardboard box of sufficient size to hold two or three children. They also converted the small pool into a place to share books. With these additions to the play space, they watched to see what the infants did in response.

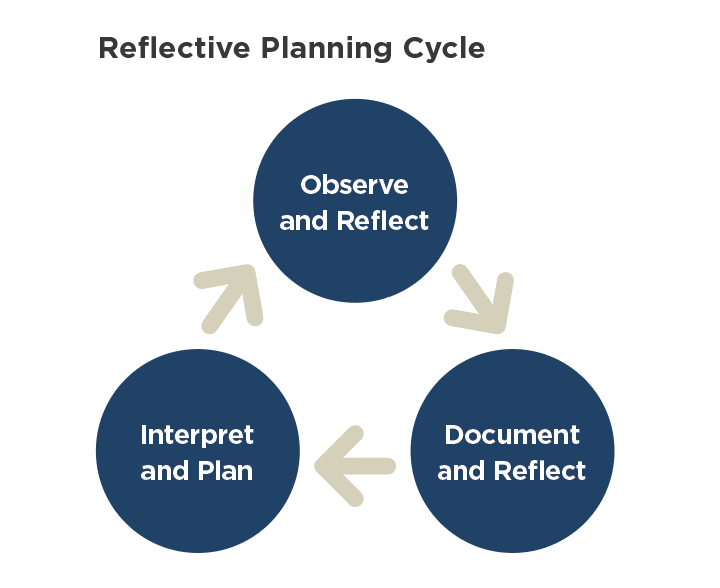

This illustrates a reflective planning cycle (see “Reflective Planning Cycle” below) that begins with observing and then continues as teachers document and interpret significant moments (California Department of Education 2016; Maguire-Fong 2020). When teachers share what is documented with others and interpret its meaning, they generate ideas for what context to offer next to support infants in going deeper in their explorations (Lally & Mangione 2006). Once teachers prepare and offer a new context, the cycle begins anew, observing, documenting, and interpreting to guide curriculum and to identify emerging skills and concepts.

Reprinted and adapted by permission of the Publisher. From Mary Jane Maguire-Fong, Teaching and Learning with Infants and Toddlers: Where Meaning-Making Begins, 2nd Edition. New York: Teachers College Press. Copyright © 2020 by Mary Jane Maguire-Fong. All rights reserved.

Daily Routines as a Context for Learning

The reflective planning cycle also supports teachers in designing routines as contexts for learning. Infants and toddlers in early learning settings experience a series of routines that mark their day, and each routine is a context for learning about self and other. The first daily routine is the baby’s arrival, coupled with the family member’s departure. It is helpful to plan with the family a departure ritual that can be repeated each day and that gives infants an opportunity to actively participate. To begin, a teacher might acknowledge how the departure feels to the parent and to the baby, saying, for example: “It’s hard to think about your baby being upset when you leave. Babies are often sad when they see their parents leave. Let’s explore how we might help your baby learn to make sense of your leaving. Over time, she’ll come to associate the sadness of seeing you leave with the joy that comes when you return.”

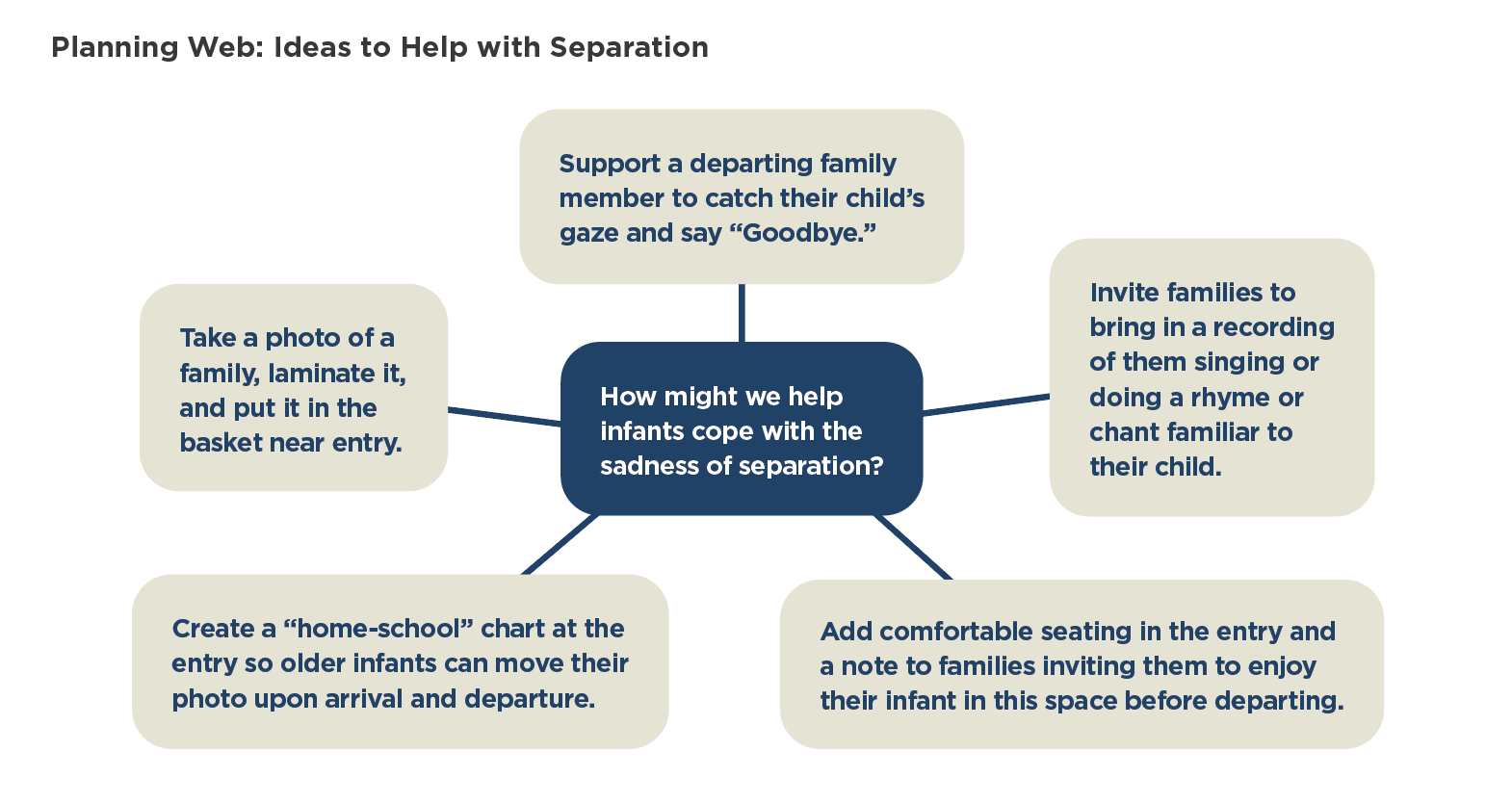

The goal is to acknowledge a family’s desire to protect the baby from sadness, to invite the family to consider how their child is trying to make sense of this emotionally trying experience, and to brainstorm ideas with the family that respect infants’ attempts to make sense of the departure. “Plan of Possibilities: A Goodbye Ritual,” as shown below, documents what occurs when teachers Vicki and Jodie plan with a family a good-bye ritual. “Planning Web: Ideas to Help with Separation,” illustrates how these ideas are recorded on a planning web.

Plan of Possibilities: A Goodbye Ritual

Context: With the infants’ families, we are creating goodbye rituals, including the departing family member gesturing and saying goodbye as the infant watches. We also have a new collection of laminated family photos, available in a basket near the entry.

Planning Question: Will a predictable goodbye ritual help infants cope with separation?

Observation: As her father tells her that he is going to work, Stella follows him to the doorway gate. She watches as he exits through the gate, waves, and says, “Goodbye, Stella. I’ll be back.” She drops to the floor, her eyes clenched shut and face grimaced, and begins to cry. Her father stoops to catch her gaze and she sees him send her a goodbye kiss. He says again, “Goodbye. I’ll be back. I am going to work.” Still crying, she watches him leave, then turns and crawls toward me. I help her find the photo of her family from our family photo basket. She clutches it and gazes at it.

Interpretation: Stella was a sad-yet-involved and active participant in this new goodbye ritual. As soon as her father closed the gate to the exterior hallway and moved out of her view, Stella crawled toward me, her primary care teacher. Her sobs ceased by the time she reached me. She seemed to calm as she looked at the photo of her family. If we repeat this each day, I think she will have the certainty of knowing that her father has departed. Also, she will begin to associate the phrase, “Goodbye. I’ll be back,” with, “Hello! I came back!”

Reprinted and adapted by permission of the Publisher. From Mary Jane Maguire-Fong, Teaching and Learning with Infants and Toddlers: Where Meaning-Making Begins, 2nd Edition. New York: Teachers College Press. Copyright © 2020 by Mary Jane Maguire-Fong. All rights reserved.

Reprinted and adapted by permission of the Publisher. From Mary Jane Maguire-Fong, Teaching and Learning with Infants and Toddlers: Where Meaning-Making Begins, 2nd Edition. New York: Teachers College Press. Copyright © 2020 by Mary Jane Maguire-Fong. All rights reserved.

Conversations and Interactions as a Context for Learning about Self and Other

A third context for learning are the many conversations and interactions with infants and toddlers that occur throughout the day. What distinguishes this from the other two contexts—play space and routines—is that the focus in planning is on what the teacher intentionally says or does to support infants’ understanding. To thoughtfully propose possibilities for talking and interacting with infants in ways that support social and emotional growth, teachers can adopt the approach of a researcher by listening and observing to discover what children reveal through actions, gestures, or vocalizations.

Carol Grivette, a teacher at the American River College Children’s Center, documented this interaction as she observed the toddlers at play:

Nate, 25 months old, draws on a paper, and I say, “I see you are making marks on the paper.”

“Lola,” he responds.

“Oh, you are drawing Lola!” I remark.

He looks at me and repeats, “Lola.” I give him a new piece of paper, on which he makes small marks, all the while repeating, “Lola.”

“You are drawing Lola this time too, aren’t you?” I say.

Nate’s smile grows wider, and he sings, “Lola, Lola, Lola,” before saying, “Eyes, ears.”

“Oh, those are Lola’s eyes and ears,” I reply.

He makes more marks and says, “Lola, me.”

“And that’s you, Nate.” I say.

At pick-up time, I show Nate’s mother the drawing. She explains that “Lola” is what Nate calls his grandmother, who has recently departed on a trip. She adds that Nate is very close to his grandmother.

Nate’s markings are more than just scribbles—they reveal his thoughts and feelings. Nate expresses through his marks his story of missing Lola. After reviewing her documentation of her interaction with Nate and her conversation with his mother, Carol and her coteachers decided to listen more closely whenever the older infants explored the writing tools. They wanted to listen for other examples of children revealing feelings or thoughts as they draw.

This vignette illustrates how very young children communicate feelings and thoughts through one-word responses, gestures, facial expressions, and actions. Documentation, when shared and interpreted together with coworkers and infants’ families, generates ideas for what to offer next to support children in making sense of what may feel like confusing and troubling feelings. In other situations, not uncommon in infant care, those feelings might lead to actions that cross the boundaries of acceptable behavior. Infants and toddlers may bite or hit others, resist trusted caregivers’ requests, or erupt in tantrums. At times, such behavior is sparked by curiosity, and at other times, it is fueled by feelings of anger or frustration. This not unlike the frustration a lost traveler might feel in an unfamiliar country, surrounded by an unfamiliar language. In each situation, a trusted guide can provide helpful support in making sense of what to do, how to do it, or where to go next.

A crawler approaches another crawler and, with a look of curiosity, tugs on this child’s hair, causing the child to cry. A nearby teacher sees this, approaches quickly, and says to the crying child, “Ooh, that hurt,” while simultaneously touching both of the children’s hair, and then saying: “Gently, no pulling hair. Pulling hair hurts. Gentle touches, not rough.”

With older infants and toddlers, a conflict might arise when two children want the same toy. “Plan of Possibilities: Using Clear Limits and Redirection,” below, illustrates how a group of teachers proposes a plan of possibilities designed to support older infants in figuring out what it means to have and to give, and in time, to build understanding of the concept of sharing.

When conflicts arise, infants and toddlers struggle to cope with intense feelings, and they rely on the thoughtful words and actions of a caring adult to help them hold and contain strong feelings, while simultaneously resolving a distressing situation (Maguire-Fong & Peralta 2019). With thoughtful words and actions, teachers acknowledge strong feelings or desires, clearly describe what children may not do and why, and clearly describe what they may do instead (Maguire-Fong 2020).

Rather than seeing misbehavior as simply a disruption to end and move beyond, it helps to see it as a context for learning that deserves thoughtful planning.

Plan of Possibilities: Using Clear Limits and Redirection

Context: Among the older infants, we have noticed more frequent conflicts over possession of a desired object.

Planning Question: How will the children respond when we clearly acknowledge their feelings, intention, or desire; describe what they did that was not acceptable and why; and clearly state what is acceptable the next time this situation arises?

Observation: I see Jackson hold tightly to the handlebar of a trike, as Linnea attempts to push him off the trike. I approach, kneel between them, and say, “Linnea, I will not let you push Jackson off the trike. I can see that you are angry and that you really want the trike, but Jackson is still using it. You can ask him, ‘Please, may I use the trike?’” I watch and wait. Linnea frowns and silently looks down. I say to Jackson, “Linnea wants to use the trike too, so when you are through, you can give it to her.” Linnea, still frowning, looks at Jackson and says, “My trike,” but she does not attempt to grab the trike.

Interpretation: Linnea wants the trike and is dismayed because Jackson has it. Because she sees him as the one keeping her from the trike, I understand why she tries to push him off the trike. After all, he is the obstacle keeping her from the trike. I also understand her anger, but I cannot let her push him off the trike. I acknowledge her anger, but, in the same breath, I tell her that she may not push him off the trike. I want her to learn that pushing others in hurtful ways is not acceptable. Because I also want her to know what to do the next time she finds herself in this situation, I give her a phrase to use to request the trike. In her own way, she asks Jackson for the trike and resists pushing him.

When teachers listen well to the stories that infants and toddlers tell through actions, gestures, and expressions and when teachers hold these stories in mind by documenting, sharing, and interpreting them together, they find ways to help infants and toddlers master the challenge and experience the joy of making and keeping friends. In short, when observant and reflective teachers plan thoughtful play spaces, daily routines, and conversations and interactions as contexts for learning, they help infants and toddlers find answers to the questions, “Where’s my family?” and “Who’s my friend?”

References

California Department of Education. 2011. The Integrated Nature of Learning. Sacramento, CA.

Gerber, M. 2002. Dear Parent: Caring for Infants with Respect. 2nd ed. Ed. J. Weaver. Los Angeles, CA: Resources for Infant Educarers.

Hamlin, J., & K. Wynn. 2012. “Young Infants Prefer Prosocial to Antisocial Others.” Cognitive Development 26 (1): 30–39.

Hamlin, J., K. Wynn, & P. Bloom. 2010. “Three-month-olds Show a Negativity Bias in Their Social Evaluations.” Developmental Science 13 (6): 923–29.

Hamlin, J., K. Wynn, P. Bloom, & N. Mahajan. 2011. “How Infants and Toddlers React to Antisocial Others.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108 (50): 19931-19936.

Lally, R. 2009. “The Science and Psychology of Infant-Toddler Care: How an Understanding of Early Learning has Transformed Child Care.” Zero to Three 3 (2): 47–53.

Maguire-Fong, M.J. 2020. Teaching and Learning with Infants and Toddlers: Where Meaning-Making Begins, 2nd ed. New York: Teachers College Press.

Maguire-Fong, M.J., & M. Peralta. 2019. Infant Development from Infancy to Age 3: What Babies Ask of Us. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Markova, G., & Legerstee, M. 2006. “Contingency, Imitation, and Affect Sharing: Foundations of Infants’ Social Awareness.” Developmental Psychology 42(1): 132–41.

Meltzoff, A., & M. Moore. 1983. “Newborn Infants Imitate Adult Facial Gestures.” Child Development 54 (3): 702–09.

Paley, V.G. “Who Will Save the Kindergarten?” Paper presented at the National Association for the Education of Young Children Annual Conference, Orlando, FL, November 2, 2011. NAEYC.org/content/who-will-save-kindergarten.

Rapacholi, B.M., Meltzoff, A.N., Rowe, H., & Toub, T.S. 2014. “Infant, Control Thyself: Infants’ Integration of Multiple Social Cues to Regulate their Imitative Behavior. Cognitive Development 32: 46–57.

Reddy, V. 2008. How Infants Know Minds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rogoff, B. 2003. The Cultural Nature of Human Development. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Rinaldi, C. 2006a. “Creativity, Shared Meaning, and Relationships.” In Concepts for Care, eds. J. R. Lally, P. L. Mangione, & D. Greenwald, 21-23. San Francisco: WestEd.

Rinaldi, C. 2006b. In Dialogue with Reggio Emilia: Listening, Researching, and Learning. New York, NY: Routledge.

Trevarthen, C. and Bjørkvold, J.R. 2016. Life for learning: How a young child seeks joy with companions in a meaningful world. In Contexts for Young Child Flourishing: Evolution, Family and Society, eds. D. Narvaez, J. Braungart-Rieker, L. Miller- Graff, L. Gettler, & P. Hastings, 28–60. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Trevarthen, C., & J. Delafield-Butt. 2017. “Intersubjectivity in the Imagination and Feelings of the Infant: Implications for Education in the Early Years.” In Under-Three Year Olds in Policy and Practice. Policy and Pedagogy with Under-Three-Year-Olds: Cross-Disciplinary Insights and Innovations, eds. E.J. White & C. Dalli, 17–39. Singapore: Springer.

Trevarthen, C., J. Delafield-Butt, & A. Dunlop. 2018. The Child’s Curriculum: Working with the Natural Values of Young Children. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Warneken, F., & M. Tomasello. 2007. “Helping and Cooperation at 14 months of Age.” Infancy 11 (3): 271–94.

Photographs: Courtesy of the author

Copyright © 2021 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

Mary Jane Maguire-Fong, MS, is professor emerita at American River College, and a former teacher and administrator for birth to age 5 programs serving migrant farmworker families. She is author of Teaching and Learning with Infants and Toddlers: Where Meaning Making Begins, and co‐author of Infant Development from Conception to Age 3: What Babies Ask of Us.