We Are Makers: Culturally Responsive Approaches to Tinkering and Engineering

You are here

Editors’ Note

Hannah Kye takes readers into two preschool classrooms that are deep in family-centered projects focused on babies. In “The Preschool Birth Stories Project,” the children are absorbed in family narratives about their own and their classmates’ births. Through their interest in other families’ stories, they gain knowledge about birth and respect for others’ experiences. Family members become actively engaged in the children’s learning, sharing their stories in the classroom and consulting with teachers about the direction of the project.

In the companion article, “We Are Makers,” interactions between the children and a visiting family member inspire a new project focused on babies. The preschoolers are making babies’ beds, and they proudly share photos of themselves as infants sleeping in a Filipino hanging bed, in a Korean wrap on a mother’s back, and on the floor amidst dancing children. Kye focuses on the importance of culturally responsive pedagogy, encouraging and guiding educators to use their teaching expertise to foster culturally responsive making, to affirm children’s racial and cultural identities, and to help all children see themselves and others as capable inventors, scientists, and engineers.

Reviewing the events and learning during these projects, Kye makes strong cases for the benefits of engaging families in an early childhood curriculum and for using culturally responsive pedagogy toward equitable and playful content learning. These approaches to learning help create and maintain strong home-school connections and advance equity in early childhood education.

In the center of our classroom, Minhui’s mother gently pours water over her baby’s legs as they kick against the edge of the bathtub. Minhui and her classmates pour water over their baby dolls. “Your babies may need a nap after splashing in the tub,” she tells the children.

“Where is your baby going to take a nap?” asks Remi.

“I have to drive home, so she may fall asleep in her car seat,” she replies. This sparks a lively conversation.

“My baby sleeps in bed with my mommy,” says Anne.

“My cousin is only a baby, but she has her own room with her own bed. I don’t even have my own room,” Kwang shares.

“My dad said when I was a baby, I slept in a basket!” Marco adds.

Minhui’s mother inspired a series of wonderings about where babies sleep. I realized we could pursue the children’s wonderings through making. I brought in cardboard boxes and invited families to donate recyclables. Kwang and Remi stacked boxes because, they said, babies usually sleep “way up high.” Other children created baby blankets from paper and fabric scraps.

With pride, the children showed classmates photos their families had sent of them as infants sleeping in a duyan (a Filipino hanging cradle), in a podaegi (a Korean wrap on a mother’s back), and on the floor of a small room surrounded by dancing siblings.

This article shows simple ways to reframe moments that inspire children, using maker education and a family-centered focus to ensure that all children see themselves as capable creators and engineers.

Why Culture Matters in Making

Maker education engages children in designing solutions to problems, tinkering with everyday items, and applying a do-it-yourself mindset. Research has discussed positive impacts of maker education on facets of learning such as student engagement, collaboration, and self-efficacy (Papavlasopoulou, Giannakos, & Jaccheri 2017) as well as on digital literacy and creativity (Marsh et al. 2019). Yet there continues to be a disconnect between maker education and culturally responsive pedagogy (CRP) in both research and practice (Kye 2020).

CRP is an approach that works toward educational equity and against prejudice (Ladson-Billings 1995; Gay 2018). Culturally responsive teachers consider whose voices are heard and valued in their settings, and they critically reflect on how schools sustain the harmful discourse that families of color and non-English-speaking families do not care about education (Yull et al. 2018). Culturally responsive teachers amplify the voices and funds of knowledge of those on the margins, those who have long been underrepresented or misrepresented in classroom curriculum (Sun & Kwon, 2020; Boutte & Bryan 2021).

Without intentional effort to teach toward equity, early learning experiences are likely to uphold dominant perceptions of who can be a scientist or an engineer (Emdin & Lee 2012). This contributes to long-standing gaps in science and engineering outcomes for students who are Black, Latino/a, Pacific Islander, or Indigenous American (de Brey et al. 2019). Research on CRP has provided a wealth of strategies and ideas for teachers’ daily practice to foster playful, equitable learning. Making can be integrated and aligned with this ongoing work.

Facilitating Culturally Responsive Making

CRP engages teachers in working against structural racism, which includes low expectations of students of color and school curricula that provide only the worldview and experiences of White English speakers (Sleeter 2011). Teachers who use this approach

- legitimize family knowledge by making classroom learning relevant to children’s home and community experiences (Gay 2018)

- document children’s contributions to demonstrate teachers’ care and respect for children (Ladson-Billings 1995)

- shine a light on content learning to promote academic success (Howard & Terry 2011)

- affirm children’s ethnic and racial identities (Gay 2018)

The following sections illustrate how early childhood educators can foster culturally responsive making.

Legitimize Family Knowledge

Culturally responsive teachers learn about children’s social and cultural identities and contexts. When they partner with family and community members, teachers and children have opportunities to learn through others’ perspectives, experiences, ways of doing, and ways of communicating (Gay 2018).

Without intentional effort to teach toward equity, early learning experiences are likely to uphold dominant perceptions of who can be a scientist or an engineer.

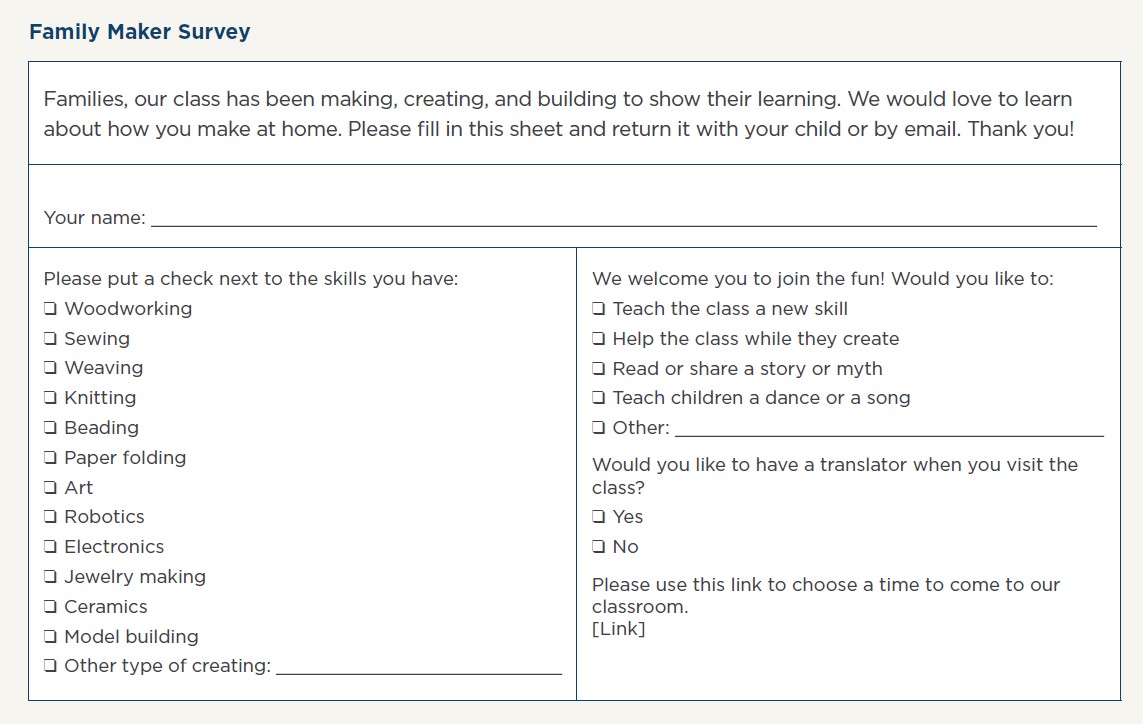

One key strategy is to survey families, then use their responses to plan and integrate their expertise into learning experiences. (See “Family Maker Survey” below for a sample.) For example, Marco’s father could not participate in the baby project during the day, but he noted on the survey that their family had a tradition of creating miniature metal sculptures. I sent home an envelope with wire, beads, and a foam block with the instructions “Create your own wire sculpture with your family. Crea tu propia escultura de alambre en familia.” Marco shared about the special tools they had at home, and we added the wire creation to our maker gallery: a table displaying the children’s creations with dictated captions for each piece. Individualized invitations, provided with translated material or through a translator, are important for families who may have linguistic, cultural, or economic reasons for feeling hesitant about participating in classroom activities (Adair & Barraza 2014).

Document Children’s Contributions

Teachers use documentation to honor and guide children’s strengths and interests. By spending time immersed in a project, educators can extend and deepen children’s engagement and conceptual development. For example, as children focused on babies and caregiving, the classroom loft transformed from a doll storage area to a plush sleep space, a bustling kitchen, and a “baby school.” I posted photos of various iterations of the loft and quotes from children working there. This encouraged children to build on each other’s expertise and discoveries. In a culturally responsive classroom, children experience learning as collaborative and reciprocal (Ladson-Billings 1995). When teachers document and help children reflect on their learning and engagement, children can feel care and a sense of belonging—central features of a culturally responsive classroom.

Shine a Light on Content Learning

Culturally responsive teachers have high academic aspirations for each and every child, including children of color and children from economically challenged backgrounds. They use teachable moments to strengthen children’s content-specific skills, including in literacy and language (Howard & Terry 2011). This practice can be applied to making.

Benefits abound when science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) concepts are integrated into early childhood settings, such as by introducing vocabulary and open-ended questions while children inquire, explore, and invent. Teachers can use words such as engineer, plan, design, and improve when narrating children’s tinkering, along with technical terms such as balance and stability (Gold, Elicker, & Beaulieu 2020).

On a display about taking apart battery-operated baby toys, I included the caption: “Parts you might find: battery, bulb, wire, switch, motor, button, speaker. What does each part do? Lo que podrías encontrar: batería, bombilla, cable, interruptor, motor, botón, altavoz. ¿Qué hace cada cosa?” Providing translations into children’s home languages for a few key words helps to validate the use of other languages in engineering and can support children in communicating ideas at school and at home. Educators can also point out that engineers helped to design and improve the human-made objects they encounter in their projects, like a stroller or the latch on a baby gate.

To ensure all children can access challenging work, teachers can model new maker skills and display and talk about learning center directions or charts that contain pictures and home languages. These practices support children’s engagement in sophisticated levels of problem posing and problem solving and can cultivate confidence for later engineering.

Affirm Children’s Racial and Ethnic Identities

A commitment to equity means acknowledging and responding to the significance of race and ethnicity in learning and development. Culturally responsive teachers clearly and consistently affirm children’s racial, ethnic, and cultural identities because they recognize the vital role these attributes play in helping young children construct positive self-concepts (Wanless & Crawford 2016). In our babies project, I learned from families and my research about the history and reasons for using a duyan, a podaegi, and a floor bed. Then, I was able to draw out cultural connections in conversations about their family photos and in the children’s play. Teachers can apply critical analysis to making: When we read or talk about makers and making, who and what is included and excluded? Teachers can learn about the contributions of makers who share racial, ethnic, or cultural backgrounds with each and every child. This sustains and affirms their own identities (Boutte & Bryan 2021).

Whether one’s students are Black, Latino/a, Pacific Islander, or Indigenous American, it is essential to learn about scientists and engineers who are. Then, when teachers share examples with the class, they draw from a multicultural knowledge base. Likewise, when the class encounters unfair portrayals and stereotypes, teachers are prepared to speak against bias and offer counterexamples. (See “Additional Resources,” included with the online version of this article at NAEYC.org/yc/winter2022, for a list of online resources about exceptional STEM thinkers and doers from diverse backgrounds.)

Conclusion

With maker education now part of early childhood classrooms, it is important to ground this work in inclusive theories and practices. The four principles used in the babies project draw from research and build on teachers’ existing skills to provide guidance for facilitating early engineering in culturally responsive ways.

Additional Resources

- Society of Women Engineers publishes an accessible blog with stories of diverse engineers and “day in the life” posts as well as a podcast, a magazine, and research on diversity in STEM.

- National Society of Black Engineers provides a podcast, magazines, and a video gallery, including clips from their programs for children.

- We Need Diverse Books features book lists and a book-finding app. The website also includes links to equity-focused organizations, Black-owned bookstores, and resources for parents and teachers.

- The Brown Bookshelf showcases children’s books by African American authors and illustrators.

- NAEYC Interest Forums engage members in dialogue in online communities such as the Latino Interest Forum, the Technology and Young Children Forum, and Diversity and Equity Education for Adults.

Copyright © 2022 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

Adair, J.K., & A. Barraza. 2014. “Voices of Immigrant Parents in Preschool Settings.” Young Children 32 (4): 32–39.

Boutte, G., & N. Bryan. 2021. "When Will Black Children Be Well? Interrupting Anti-Black Violence in Early Childhood Classrooms and Schools.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 22 (3): 232–243.

de Brey, C., L. Musu, J. McFarland, S. Wilkinson-Flicker, M. Dilibert, A. Zhang, C. Branstetter, & X. Wang. 2019. Status and Trends in the Education of Racial and Ethnic Groups 2018 (NCES 2019-038). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2019/2019038.pdf.

Emdin, C., & O. Lee. 2012. “Hip-Hop, the ‘Obama Effect,’ and Urban Science Education.” Teachers College Record 114 (2): 1–24.

Gay, G. 2018. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Gold, Z.S., J. Elicker, & B.A. Beaulieu. 2020. “Learning Engineering through Block Play: STEM in Preschool.” Young Children 75 (2): 24–29.

Howard, T., & C.L. Terry Sr. 2011. “Culturally Responsive Pedagogy for African American Students: Promising Programs and Practices for Enhanced Academic Performance.” Teaching Education 22 (4): 345–362.

Kye, H. 2020. “Who Is Welcome Here? A Culturally Responsive Content Analysis of Makerspace Websites.” Journal of Pre-College Engineering Education Research 10 (2): 1–16.

Ladson-Billings, G. 1995. “Toward a Theory of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy.” American Educational Research Journal 32 (3): 465–491.

Marsh, J., E. Wood, L. Chesworth, B. Nisha, B. Nutbrown, & B. Olney. 2019. “Makerspaces in Early Childhood Education: Principles of Pedagogy and Practice.” Mind, Culture, and Activity 26 (3): 1–13.

Papavlasopoulou, S., M.N. Giannakos, & L. Jaccheri. 2017. “Empirical Studies on the Maker Movement, a Promising Approach to Learning: A Literature Review.” Entertainment Computing 18: 57–78. (Special issue, SI: Maker Technologies to Foster Engagement and Creativity in Learning)

Sleeter, C.E. 2011. “An Agenda to Strengthen Culturally Responsive Pedagogy.” English Teaching: Practice and Critique 10 (2): 7–23.

Sun, W., & J. Kwon. 2020. "Representation of Monoculturalism in Chinese and Korean Heritage Language Textbooks for Immigrant Children." Language, Culture and Curriculum 33 (4): 402–416.

Wanless, S.B., & P.A. Crawford. 2016. “Reading Your Way to a Culturally Responsive Classroom.” Young Children 71 (2): 8–15.

Yull, D., M. Wilson, C. Murray, & L. Parham. 2018. "Reversing the Dehumanization of Families of Color in Schools: Community-Based Research in a Race-Conscious Parent Engagement Program." School Community Journal 28 (1): 319–347.

Hannah Kye, EdD, is an assistant professor of interdisciplinary and inclusive education at Rowan University. Her research interests include family-centered curriculum and early STEM education with a focus on equity and diversity. She teaches preservice teachers and provides professional development for in-service teachers. [email protected]