The Preschool Birth Stories Project: Developing Emergent Curriculum with Families

You are here

Editors’ Note

Hannah Kye takes readers into two preschool classrooms that are deep in family-centered projects focused on babies. In “The Preschool Birth Stories Project,” the children are absorbed in family narratives about their own and their classmates’ births. Through their interest in other families’ stories, they gain knowledge about birth and respect for others’ experiences. Family members become actively engaged in the children’s learning, sharing their stories in the classroom and consulting with teachers about the direction of the project.

In the companion article, “We Are Makers,” interactions between the children and a visiting family member inspire a new project focused on babies. The preschoolers are making babies’ beds, and they proudly share photos of themselves as infants sleeping in a Filipino hanging bed, in a Korean wrap on a mother’s back, and on the floor amidst dancing children. Kye focuses on the importance of culturally responsive pedagogy, encouraging and guiding educators to use their teaching expertise to foster culturally responsive making, to affirm children’s racial and cultural identities, and to help all children see themselves and others as capable inventors, scientists, and engineers.

Reviewing the events and learning during these projects, Kye makes strong cases for the benefits of engaging families in an early childhood curriculum and for using culturally responsive pedagogy toward equitable and playful content learning. These approaches to learning help create and maintain strong home-school connections and advance equity in early childhood education.

“This is me in my mommy’s uterus. My mommy and Appa called me Bluebins because I was small like a blueberry.”

Chonghui sits in the dramatic play area, holding up artifacts her mother had shown in her preschool classroom the day before: an ultrasound image and photos of her mother when she was pregnant and of Chonghui as a newborn in the hospital and at home. Just as her mother did in front of her class, Chonghui tells a classmate the story of her birth, her voice and expressions conveying emotions from anticipation to exhilaration, exhaustion, and love. The swell of emotions around birth is a universal experience, and narratives of these moments can bridge cultural worlds.

Today’s early childhood educators must steer a course among the varied expectations and goals of their school leaders, state standards, prescriptive curricula, and the diverse children and families with whom they work. As Reid and Kagan (2015) note, “The field of early childhood education is experiencing unprecedented public investment accompanied by increasing expectations for enhanced child outcomes” (1). By sharing a story from the field, I aim to shed light on effective processes and principles for navigating this work while keeping children and families at the center of practice.

This article explores a flexible and accessible project that involved families in the development of an emergent curriculum. Recent studies of emergent curriculum have tended to focus on the teacher-child dyad, with the teacher leading children in explorations relevant to children’s expressed interests or curiosity (Stacey 2018; Sweeney & Fillmore 2018). Building on this, the birth stories project engaged family members, teachers, and children as coleaders and coexplorers.

The article touches on culturally responsive pedagogy, or teaching that is responsive to the diversity in a classroom. By incorporating children’s backgrounds and funds of knowledge, this approach makes learning “culturally recognizable and socially meaningful” to all learners (Howard & Terry 2011, 347). Culturally responsive teachers are committed to teaching a variety of perspectives and fostering cross-cultural respect, empathy, and community. For a more detailed discussion of culturally responsive pedagogy, see “We Are Makers: Culturally Responsive Approaches to Tinkering and Engineering,” below.

Purpose: Why Birth Stories?

In a university-based early childhood center in New Jersey, two preschool children’s mothers were pregnant and several others had recently welcomed siblings. Children raised questions about birth and families during lunchtime conversations and in dramatic play scenarios. As a professor in the university program affiliated with the center, I noticed this theme emerging during my weekly visits. I had told my daughter’s birth story to her classmates when she was in preschool, and I talked with the preschool teachers about initiating a similar project. They noted that it could engage more families in the classroom, which tends to be a challenge for many early learning programs.

Chapters from two books have documented the powerful connections made through sharing birth stories in classrooms. In “Oral Histories in the Classroom: Home and Community Pedagogies,” Carmona and Bernal write about an oral history project for students in grades 2 to 6 to connect teachers and families “across time, space, generations, and across educational and institutional boundaries” (2012, 115). The mothers who shared stories from their family histories and from the children’s births acknowledged the value of their children learning about and preserving their cultural and familial stories.

In “Our Stories to Transform Them: A Source of Authentic Literacy,” Arrastia (1995) writes of a similar project in a mother’s reading program in which mothers generated and wrote childbirth stories. The women were enrolled in adult basic education and English as a second language classes. Arrastia writes,

Even those stories of the earliest moments of life were shaped by our families’ own stories and myths. . . . In telling our stories, learning each other’s stories, and finding the strength and value in our stories, we began to change the stories and our roles as protagonists. (107–108)

These two examples illustrate the potency of sharing family histories to both empower and connect the participants—central components of culturally responsive pedagogy.

Perspective: Connections Between Family Engagement and Emergent Curriculum

Emergent curriculum has roots in the Reggio Emilia approach, an influential model of early childhood education that was initiated by parent cooperatives in the city of Reggio Emilia, Italy, and directed by Loris Malaguzzi (1924–1994) (Rinaldi 2006). Malaguzzi viewed children as having three teachers: the early childhood educator, the environment, and the parent. Rather than passively receiving knowledge, children are seen as capable of actively constructing their own knowledge as they encounter and dialogue with these three teachers. Children’s learning begins with their motivations and interests, and it is the work of families and educators to recognize and build on children’s learning based upon their strengths, inclinations, and wonderings. This is the heart of emergent curriculum.

Emergent curriculum has roots in the Reggio Emilia approach, an influential model of early childhood education that was initiated by parent cooperatives in the city of Reggio Emilia, Italy, and directed by Loris Malaguzzi (1924–1994) (Rinaldi 2006). Malaguzzi viewed children as having three teachers: the early childhood educator, the environment, and the parent. Rather than passively receiving knowledge, children are seen as capable of actively constructing their own knowledge as they encounter and dialogue with these three teachers. Children’s learning begins with their motivations and interests, and it is the work of families and educators to recognize and build on children’s learning based upon their strengths, inclinations, and wonderings. This is the heart of emergent curriculum.

Research and guidance on emergent curriculum focus on developing rich, inspiring environments for learning (Biermeier 2015; Sunday 2020) and on the reflective, responsive teacher-child dyad (Vanegas-Grimaud 2017). Current interpretations may only briefly involve one parent who has expertise relevant to a particular project. For example, in a classroom where children became interested in designing buildings, the teacher invited one mother, an architect, to talk about blueprints (Stacey 2018). Such encounters are important for engaging families in children’s learning, yet more can be done to uphold the intimate engagement of home caregivers essential to the philosophy of parent-as-teacher.

Research has shown that family engagement in school has multiple benefits for students: when family members are involved, children are more likely to adapt well to school, develop social skills and positive behaviors, do better in school, and stay longer in school (Smith et al. 2020). Beyond these benefits, family engagement can help teachers understand children by seeing them in the context of family and community, which informs teachers’ pedagogy and development of meaningful, culturally responsive curriculum.

Family engagement in school has multiple benefits: when family members are involved, children are more likely to adapt well to school, develop social skills and positive behaviors, do better in school, and stay longer in school.

Despite the benefits and expectations about effective family partnerships (NAEYC 2020), family involvement in educational settings is often limited to passive participation, such as attending family-educator conferences and reading school newsletters, emails, or other items sent home (Ishimaru 2019). The preschool birth stories project helped close the gap between home and school in this preschool setting.

Project Goals and Strategies

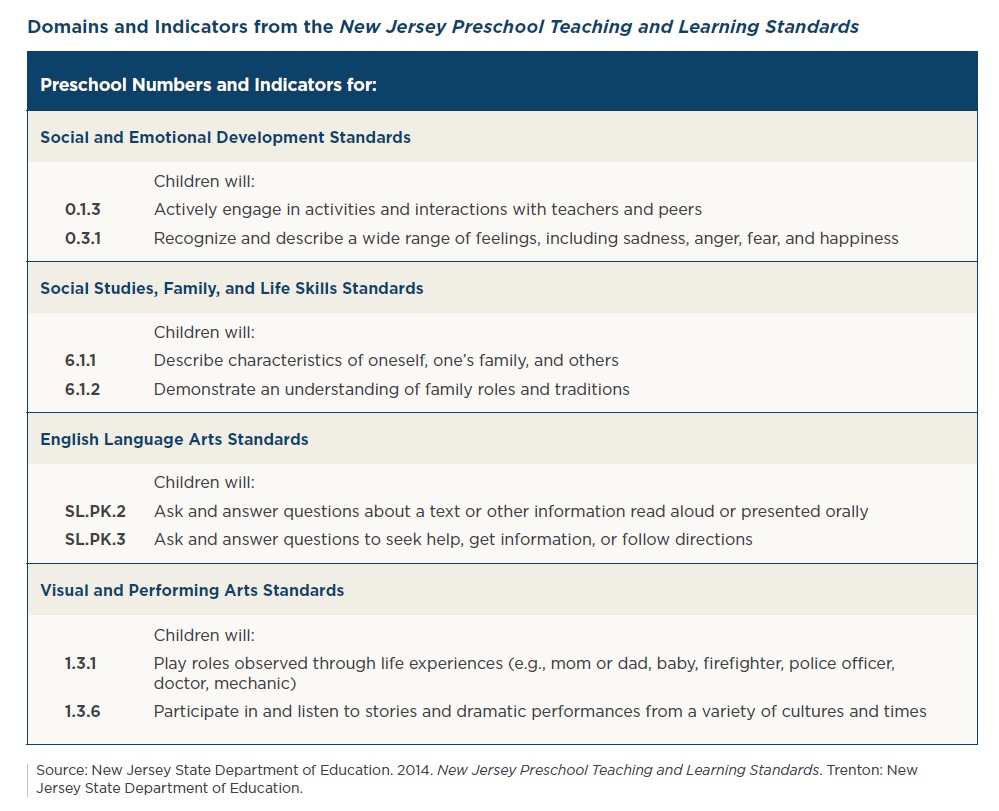

In the fall of the program year, before beginning the project, I met with the lead preschool teacher, Leah, who was also the center director. We discussed nurturing the children’s interest in birth stories, and we defined goals for teachers and families as well as for children. We reviewed guidelines for child outcomes based on the New Jersey Preschool Teaching and Learning Standards (New Jersey State Department of Education 2014). The standards are intended to reflect research on developmentally appropriate content and outcomes. In contrast to the more common focus on academic content knowledge in K–12 standards, preschool standards often include expectations for social and emotional development (along with cognitive, physical, arts, and language standards). This is because young children’s competence in this domain powerfully impacts school readiness and later academic success (Harrington et al. 2020).

While a standardized curriculum aims to replicate predetermined outcomes among students, emergent curriculum requires teachers to be attuned and responsive to individual children in the classroom. We used several of the New Jersey preschool standards as a fluid guide for our community exploration rather than as a tool to achieve prescriptive outcomes for all children. (See “Domains and Indicators from the New Jersey Preschool Teaching and Learning Standards,” below, for more.)

We used the following four principles, drawn from my previous classroom experiences, to guide work with families and to ensure respectful, effective collaboration.

Plan in Broad Strokes

Leah and I began the project with the question “What knowledge are the children actively seeking?” We introduced a provocation to spark children’s interest: one child’s mother came to the classroom to read aloud On the Night You Were Born, by Nancy Tillman, and to tell the birth story of her daughter, Chonghui. Afterward, I typed and posted a summary of the story in the dramatic play area, along with accompanying photos. This provocation motivated children to ask their families when they could come and share their birth stories and add their photos to the area.

Upon observing the children’s interest in continuing the exploration, Leah and I planned in broad strokes. We added baby dolls to the dramatic play area, curated the bookshelf to include family stories, posted a notice on the bulletin board that asked family members to add ideas and resources, and invited all families by email to share their experiences. Through encounters with families and with the enriched environment, children had the encouragement, resources, and freedom to pursue their interests and deepen their understandings of families.

The email was sent to all 12 preschool families in the spring of that program year, and each family scheduled a time to share their story during the next few months. Along with Leah’s mother, who told the story of Leah’s birth via video call, a total of 13 families participated. Leah noted that this was the first project in her decade of working at the center that gained full family participation.

Planning in broad strokes meant that family members could take part in curriculum making in their own distinctive ways. Some sat on the carpet and told their stories from memory. Two families prepared posters with photos and artifacts, one family showed videos from the day of birth, and two created presentation slides. Eager to share more details from their family stories and to discuss next steps for our project, most continued conversations with us about the curriculum outside of the classroom.

Shape the Curriculum from Family Perspectives and Knowledge

Emergent curriculum validates the active creation of knowledge through personal connection rather than only the absorption of facts from books and lesson plans. In this project, families shared stories as a means of connecting with the children and of “provoking occasions of discovery” (Edwards 1998, 182). Leah invited the children to interview family members after each story. Because the topic was important to them, the preschoolers actively pursued discovery and meaning making in these dialogues.

For example, during her story, Dylan’s mother, Tanya, told the children that Dylan was born early and showed pictures from his neonatal intensive care unit. The children asked questions to learn more; Tanya’s responses illustrated how a family member’s presence, perspective, and experiences shaped community knowledge about birth and families.

Aaron: How can you give him a bath?

Tanya: I would take him out of his little incubator, and they would bring his bathtub into the room. It was a little tiny bathtub. We would wash him with a sponge and rinse him off. Then they would take the bathtub away and dress him in tiny little clothes, about the size of doll clothes. It was challenging because he had all those wires and tubes. I had to be careful when I was holding him with those tubes.

Dylan: Why was the feeding tube in my nose in this picture?

Tanya: They switched it sometimes from your mouth to your nose. You could not eat on your own, so the tube went right from your nose to your tummy.

Chonghui: Why is Dylan named Dylan?

Tanya: I liked that name for a long time, and my great-grandpa was named Dylan.

The interviews not only advanced the class’s collective knowledge about birth and families but also became opportunities for families and teachers to learn more about children’s understandings and wonderings. The children’s questions and comments demonstrated an understanding of family roles and traditions (social studies standard 6.1.2), such as bathing and naming, as well as an ability to ask effective questions about an oral presentation to gain information (English language arts standards SL.PK.2 and SL.PK.3) (New Jersey State Department of Education 2014).

Through these encounters, children learned to treat others’ thoughts, questions, and memories seriously and with respect. They actively worked to make meaning from moments of surprise, such as seeing a photo of a classmate as a tiny newborn affixed to wires. Families’ knowledge and voices became interwoven in classroom life as children carried themes into their dramatic play and had conversations about birth and families.

Document Learning in Ways that Support Family-Teacher Collaboration

In emergent curriculum, documentation serves three major functions: to provide children with a memory of their work to expand and inspire further inquiry; to provide teachers with tools for research and reflection; and to provide families with detailed information about the curriculum to facilitate their engagement (Hewett 2001). The birth stories documentation panels (bulletin boards showing children’s learning through photos and quotes) received much attention from families. Before and after school, family members and children visited the panels to read and talk about reflections on the learning taking place.

It was essential for us to represent community knowledge to ensure families would be alert to opportunities to guide and co-construct knowledge with their children. Throughout the project, and with participants’ permission, I posted excerpts from classroom conversations on the hallway bulletin board to record children’s meaning making. Each visiting family member asked Leah about how much detail to provide in their stories and which details would be appropriate to share with children. One of the transcripts I posted made a noticeable difference in their comfort with sharing their stories.

Teachers offered additional stories and diverse perspectives through books (see “Books that Supported a Birth Stories Project” below), and they posted excerpts of conversations for families’ reference. Throughout the project, documentation was developed in response to questions from families and with the intent of validating and supporting them as coeducators.

Nurture Family Bonds Through Curriculum

Prosocial behaviors and having positive interactions with others are key early social and emotional skills. Children do not acquire these skills and knowledge in a linear way through set stages; instead, some educators use the metaphor of a tree with learning growing in many directions, while others use the imagery of waves of development (NAEYC 2020). Malaguzzi spoke of knowledge as a “tangle of spaghetti,” and Rinaldi wrote of project work as a series of small narratives, each taking flight in ways that advance children’s “process of becoming” (Rinaldi 2006, 6). One can see how the skill of having positive interactions with others is entangled with cultural norms, physical and affective environments, and knowledge of self, family, and others.

Foregrounding their own family bonds encouraged children to learn in an environment of respect and empathy for other families.

Given this tangle of knowledge, as the birth stories project was woven into classroom life, Leah and I chose to focus on supporting children’s inquiry in ways that nurtured family bonds. Family relationships are the foundation for children’s engagement “in ever widening circles: from the family to the classroom community, the neighborhood, and the world” (New Jersey State Department of Education 2014, 85; NAEYC 2020). Children taught each other their favorite family activities, such as playing basketball or eating ice cream together.

Foregrounding their own family bonds encouraged children to learn in an environment of respect and empathy for other families. This became clear when Leah’s mother, Julie, visited via video call from another state. She was a stranger to the children—she had not been to the classroom or center. She shared about her belly birth (cesarean section) after they had heard three other stories involving belly births.

Lars: Why did they have to cut your belly?

Julie: When they are born, babies are usually head first or feet first.

Lars: Feet first is really dangerous.

Graham: Was she the feet way?

Julie: She was trying to touch her toes inside my belly, so when they took her out, she was heinie first!

Ben: Were you okay?

Julie: I was okay!

The children’s questions demonstrated their growing knowledge about birth as well as the power of the curriculum to connect participants across distance and generations.

Regarding the New Jersey preschool standards, children demonstrated key competencies in the emergent curriculum, such as prosocial behaviors and positive interactions (social emotional development standards 0.1.3 and 0.3.1), participating in and listening to stories (visual and performing arts standard 1.3.6), and describing characteristics of themselves, their families, and others (social studies standard 6.1.1). Leah noted that the children’s skills and knowledge exceeded her expectations because of their zeal for the project.

Conclusion

The birth stories project provides one example of how early childhood educators can keep children and families at the center of their practice. Key strategies for organizing and teaching the project included planning in broad strokes, shaping the curriculum based on family knowledge, documenting to support family collaboration, and nurturing family bonds through curriculum. The project was effective in creating partnerships with families at the preschool level and had value for children, families, and teachers.

Three decades of research on family engagement have shown that children are more successful in school when their teachers and parents work together as partners in their learning (e.g., Kagan 1984 through Epstein et al. 2018). Using guiding principles for our work with preschool families and children invigorated children’s co-construction of knowledge and meaning making about their world.

Books that Supported a Birth Stories Project

In the birth stories project, we used the following books to introduce family structures and roles that were not highlighted in the children’s birth stories. Quotes from the children shed light on children’s thinking about the books.

Jonathan and His Mommy, by Irene Smalls and illus. by Michael Hays (1992)

- “Families can be two people or 100!”

Daddy Makes the Best Spaghetti, by Anna Grossnickle Hines (1986)

- “My dad cooks a lot, like the book.”

- “Grandpa and Grandma cook sometimes.”

My Family Is Forever, by Nancy Carlson (2004)

- “People with different hair colors and different skin can become one big family.”

- “When someone adopts someone else’s baby, that becomes their baby.”

The following picture books can also support children’s understanding of their own and others’ families.

- Who Will You Be?, by Andrea Pippins (2020)

- Families Belong, by Dan Saks (2020)

- I Sang You Down from the Stars, by Tasha Spillett-Sumner (2021)

Author’s Note: My deepest thanks to the teachers, families, and children for their enthusiastic engagement and collaboration. This project would not have been possible without Leah’s partnership and dedication to honoring children and families.

Photographs: © Getty Images

Copyright © 2022 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

Arrastia, M. 1995. “Our Stories to Transform Them: A Source of Authentic Literacy.” In Immigrant Learners and Their Families: Literacy to Connect Generations, eds. G. Weinstein-Shr & E. Quintero, 101–9. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics & Delta System.

Biermeier, M.A. 2015. “Inspired by Reggio Emilia: Emergent Curriculum in Relationship-Driven Learning Environments.” Young Children 70 (5): 72–79.

Carmona, J.F., & D.D. Bernal. 2012. “Oral Histories in the Classroom.” In Creating Solidarity Across Diverse Communities: International Perspectives in Education, eds. C.E. Sleeter & E. Soriano, 114–130. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Edwards, C. 1998. “Partner, Nurturer, and Guide: The Roles of the Reggio Teacher in Action.” In The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Approach—Advanced Reflections, 2nd ed., eds. C. Edwards, L. Gandini & G. Forman, 180–197. Greenwich, Connecticut: Ablex Publishing.

Epstein, J.L., M.G. Sanders, S.B. Sheldon, B.S. Simon, K.C. Salinas, N.R. Jansorn, F.L. Van Voorhis, C.S. Martin, B.G. Thomas, M.D. Greenfeld, & D.J. Hutchins. 2018. School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Your Handbook for Action. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Harrington, E.M., S.D. Trevino, S. Lopez, & N.R. Giuliani. 2020. “Emotion Regulation in Early Childhood: Implications for Socioemotional and Academic Components of School Readiness.” Emotion 20 (1): 48.

Hewett, V.M. 2001. “Examining the Reggio Emilia Approach to Early Childhood Education.” Early Childhood Education Journal 29 (2): 95–100.

Howard, T., & C.L. Terry Sr. 2011. “Culturally Responsive Pedagogy for African American Students: Promising Programs and Practices for Enhanced Academic Performance.” Teaching Education 22 (4): 345–362.

Ishimaru, A.M. 2019. “From Family Engagement to Equitable Collaboration.” Educational Policy 33 (2): 350–385.

Kagan, J. 1984. The Nature of the Child. New York, NY: Basic Books.

NAEYC. 2020. “Developmentally Appropriate Practice.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/dap/contents.

New Jersey State Department of Education. 2014. New Jersey Preschool Teaching and Learning Standards. Trenton: New Jersey State Department of Education.

Reid, J.L. & S.L. Kagan. 2015. A Better Start: Why Classroom Diversity Matters in Early Education. Washington, DC: Poverty & Race Research Action Council.

Rinaldi, C. 2006. In Dialogue with Reggio Emilia: Listening, Researching and Learning. Oxfordshire, England: Routledge.

Smith, T.E., S.M. Sheridan, E.M. Kim, S. Park, & S.N. Beretvas. 2020. “The Effects of Family-School Partnership Interventions on Academic and Social-Emotional Functioning: A Meta-Analysis Exploring What Works for Whom.” Educational Psychology Review 32 (2): 511–544.

Stacey, S. 2018. Emergent Curriculum in Early Childhood Settings: From Theory to Practice. St. Paul, MN: Redleaf.

Sunday, K. 2020. “Dinner Theater in a Toddler Classroom: The Environment as Teacher.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 21 (3): 197–207.

Sweeney, S J., & R.M. Fillmore. 2018. “The Birds, the Children, and the Big Black Dog: Reflecting on Emergent Curriculum.” Young Children 73 (1): 69–72.

Vanegas-Grimaud, L. 2017. “The Command Center Project: Resolving My Tensions with Emergent Curriculum.” Young Children 72 (3): 60–68.

Hannah Kye, EdD, is an assistant professor of interdisciplinary and inclusive education at Rowan University. Her research interests include family-centered curriculum and early STEM education with a focus on equity and diversity. She teaches preservice teachers and provides professional development for in-service teachers. [email protected]