Inspired by Reggio Emilia: Emergent Curriculum in Relationship-Driven Learning Environments

You are here

What children learn does not follow as an automatic result from what is taught, rather, it is in large part due to the children’s own doing, as a consequence of their activities and our resources.

—Loris Malaguzzi, The Hundred Languages of Children

The author of these words, Loris Malaguzzi, was the founder and director of the renowned municipal preschools of Reggio Emilia, Italy. Malaguzzi passed away two decades ago, but we hope he would be pleased with the progress early childhood educators in North America have made toward understanding his pedagogical lessons. His philosophy—a blend of theory and practice that challenges educators to see children as competent and capable learners in the context of group work (Fraser & Gestwicki 2002)—differs from the widely accepted Piagetian perspective that views child development as largely internal and occurring in stages (Mooney 2013). Malaguzzi emphasized that “it was not so much that we need to think of the child who develops himself by himself but rather of a child who develops himself interacting and developing with others” (Rankin 2004, 82). As such, at the core of the Reggio Emilia philosophy is its emphasis on building and sustaining relationships.

Much like Vygotzky, Malaguzzi believed that social learning preceded cognitive development (Gandini 2012). He emphasized that the environment plays a central role in the process of making learning meaningful. So important was this notion, that Malaguzzi defined the environment as the third teacher (Gandini 2011). Malaguzzi’s third teacher is a flexible environment, responsive to the need for teachers and children to create learning together. Fostering creativity through the work of young hands manipulating objects or making art, it is an environment that reflects the values we want to communicate to children. Moreover, the classroom environment can help shape a child’s identity as a powerful player in his or her own life and the lives of others. To foster such an environment, teachers must go deeper than what is merely seen at eye level and develop a deep understanding of the underlying principles and of children’s thinking, questions, and curiosities.

A little more than a decade ago, Pinnacle Presbyterian Preschool, in Scottsdale, Arizona, began implementing a program directly influenced by the schools of Reggio Emilia. Inspired by the writings of Lella Gandini, we began a fond relationship with the author and educator, inviting Gandini to visit our school with regularity.

Lella Gandini is best known in North America as the leading advocate for the Reggio Emilia approach to early childhood education. Her numerous publications include writings on early childhood education and folklore, and she is coauthor or coeditor of such works as Insights and Inspirations From Reggio Emilia: Stories of Teachers and Children From North America and The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Approach to Early Childhood Education. It is through our friendship with Lella Gandini that we have implemented strategies that empower teachers to use space and materials to ignite learning. For example, teachers notice in early autumn that the children are taking an interest in spider webs on the playground. Several 4-year-olds discover the strands reflecting the sunlight on a fence post. The teachers know the finding has sparked the children’s curiosity when the children ask to photograph the web. Classroom teacher Keri Woolsey describes her response:

We try to integrate the writing and prewriting skills with the children, so I told the children, “Oh my gosh, I don’t have my camera; could you draw it for me?” They ran inside the classroom and got clipboards, paper, and markers and hurried back to the playground. And then they began to draw. Some of these kids typically don’t really want to try to write or draw, just because they are not confident with those skills. Yet here they are jumping at the task because it was meaningful to them. No matter what the drawing looked like, it was a total celebration of what they were learning.

Creating a flexible, relationship-driven learning environment

Relationships are at the very heart of the Reggio Emilia philosophy. That philosophy is reflected in an environment that encircles the child with three “teachers,” or protagonists. The first teacher—the parent—takes on the role of active partner and guide in the education of the child. The second is the classroom teacher. Often working in pairs, the classroom teacher assumes the role of researcher and intentionally engages children in meaningful work and conversation. The third teacher is the environment—a setting designed to be not only functional but also beautiful and reflective of the child’s learning. It is the child’s relationship with parent, teacher, and environment that ignites learning.

Children construct their own knowledge through a carefully planned curriculum that engages and builds upon the child’s current knowledge, recognizing that knowledge cannot simply be provided for the child. The curriculum, often emergent in nature, is based on the interests of the children. When learning is the product of the child’s guided construction rather than simply the teacher’s transmission and the child’s absorption, learning becomes individualized. Most important, teaching becomes a two-way relationship in which the teacher’s understanding of the child is just as important as the child’s understanding of the teacher.

Emergent curriculum is not a free-for-all. It requires that teachers actively seek out and chase the interests of the children. This kind of teaching environment demands a high degree of trust in the teacher’s creative abilities, and envisions an image of the child as someone actively seeking knowledge. It is a perspective that turns structured curriculum, with predetermined outcomes, on its head. A standardized curriculum that is designed to replicate outcomes often eliminates all possibility of spontaneous inquiry, stealing potential moments of learning from students and teachers in a cookie-cutter approach to education in the classroom. Given the diversity of the children we teach, accepting a canned recipe for teaching, evaluation, and assessment is problematic at best. Each child we teach is unique, requiring us to use our own judgment, instead of rules, to guide our teaching practice. To teach well, educators must ensure that creativity and innovation are always present. Although good teaching requires organization and routines, it is never inflexible and rarely routine. It dances with surprise. It pursues wonder. It finds joy at every turn.

Flexible environments allow teachers to be responsive to the interests of the children, freeing them to construct knowledge together. This is apparent in our example of the spider investigation. The teachers could simply leave behind the children’s interest in spiders, limiting the activity to the playground. Instead, they encourage the children to draw what they observe and to share those observations and drawings during class circle time. To be sure, the teachers already have an activity planned for the daily circle time; they set it aside to pursue knowledge on a subject that has sparked the children’s imaginations. One of the classroom teachers, Kristine Lundquist, describes what happened next.

We asked the children what they knew about spiders and spider webs. Living in the desert, spiders of all shapes and sizes are common. So we were not surprised when the children bubbled forth with ideas about how webs are created or stories of brave dads removing spiders from rooms in their homes. We wrote down the children’s comments and included them in the daily journal email to parents. The very next day on the playground the children were at it once again, finding and exclaiming, rather loudly, that another spider had been discovered.

The teachers take action, at first by seeking out spider storybooks in the school library and checking out non-fiction books from the local library. A chance conversation between one of the teachers and her neighbor results in the donation of a live tarantula—elevating the investigation to the next level. Parents, alerted to the spider investigation through daily email communication, begin talking and reading about spiders with their children at home. The construction of knowledge becomes apparent as children include egg sacs, spinnerets, and multiple eyes in their drawings; count off the legs of the spiders; and compare spiders to other insects found on the playground.

The teachers take action, at first by seeking out spider storybooks in the school library and checking out non-fiction books from the local library. A chance conversation between one of the teachers and her neighbor results in the donation of a live tarantula—elevating the investigation to the next level. Parents, alerted to the spider investigation through daily email communication, begin talking and reading about spiders with their children at home. The construction of knowledge becomes apparent as children include egg sacs, spinnerets, and multiple eyes in their drawings; count off the legs of the spiders; and compare spiders to other insects found on the playground.

Creating environments that reflect our values

Surprisingly, in our efforts to define best practices, we seldom address the vision of how our values are communicated through our practice. Once we get beyond standards in literacy and numeracy, what do we hope to achieve? What kind of culture do we want the children to experience in our schools? A few years ago, our staff attended a conference at one of the local community colleges presented by Deb Curtis and Margie Carter. Titled “Reflecting With the Thinking Lens,” the conference was designed to help teachers and schools cultivate creative and reflective thinking about their teaching environments (Curtis et al. 2013). Margie Carter suggested that as a teaching team we create a simple worksheet to help us consider how our values are reflected in our classroom environments.

When we evaluate the spider investigation, the worksheet reflects the learning occurring in our classroom, modifications needed to the environments, and introductions of new materials. Using evaluation tools like this, the teaching team at Pinnacle meets each week as a group and also several times during the week with classroom teaching partners. This time for teachers to learn from each other is scheduled into the week and never compromised. It is time devoted to discuss their work, their hopes and concerns, and their ideas with other colleagues. It is a recognition that learning to teach well rarely occurs during college instruction, but rather within the context of classroom experiences and discussions with colleagues. We believe that learning to teach well is a lifelong endeavor. As such, we define ourselves as colearners with our students. Behaving more as researchers, teachers provide meaning and demonstrate values as teachers and students construct learning together.

One thing we know for certain is that students will thrive in a school environment where the teachers themselves are thriving. The best schools nurture the teachers who work there as well as the students who learn within the walls. Learning from our colleagues deserves time and attention, as it opens up new ideas about what professional development should be. Changing outcomes in classrooms requires teachers to challenge what they know and what they think is developmentally appropriate, and to reach beyond pedagogical techniques. In our experience, this can happen only in an environment that is respectful of differences in viewpoint, supportive in trying something new, and mindful of the willingness of teachers to shed their sensitivity and isolation. Teachers who have grown accustomed to working alone transform their thinking into creating solutions as they share with their colleagues. This transformation in teaching practices can happen only in an environment where collaboration and discussion are highly valued.

Creating environments that foster creativity

Teaching for creativity involves asking open-ended questions where there may be multiple solutions; working in groups on collaborative projects, using imagination to explore possibilities; making connections between different ways of seeing; and exploring the ambiguities and tensions that may lie between them.

—Ken Robinson, Out Of Our Minds: Learning to Be Creative

There is much about the Reggio Emilia approach that distinguishes it from other efforts to define best practices in early childhood education. Much of the worldwide attention has been on the program’s emphasis on children’s symbolic languages, lovingly referred to as the hundred languages of children. George Forman and Brenda Fyfe (2012) describe the hundred languages of children as symbolic languages children use to express their own knowledge and desires through artwork, conversation, early writing, dramatic play, music, dance, and other outlets. Recognizing that at the very core of creativity is our desire to express ourselves, Reggio Emilia schools create environments that inspire and support creative thinking and invention. If building and sustaining relationships are to be the foundation of a learning community, then creativity must always be present. Creativity is the conduit—the instrument that allows us to communicate with and understand others.

At Pinnacle, every learning space has paper and writing instruments. In the imaginary play spaces within the classrooms and the playground outside, children are actively writing and drawing. It becomes a part of the culture of learning, a process that is internalized within the group. We have made a conscious effort to steer away from purchasing ready-made materials, such as pre-cut foam pieces or rubber stamps, and instead spend resources on paper, clipboards, and multiple forms of writing and drawing tools. Asking children to draw what they see and then revisit the subject later to add yet more detail is the very essence of scientific observation. When the tarantula joins the classroom, teachers place magnifying glasses, small clipboards with paper, and markers next to the terrarium. They place nonfiction books about spiders on the shelf near the terrarium and display close-up pictures of different kinds of spiders. Rather than instructing the children, the teachers set up the provocation and then take a step back.

In Reggio Emilia-inspired schools, teachers place great emphasis on using materials and activities that provoke investigation and group learning. As expected, being curious and inventive little people, the children are very excited about the new spider addition to their classroom. They closely watch the tarantula, using the magnifying glasses to see the details and then drawing what they observe. The conversation is lively and loud as they speculate about where the spider came from, what the spider eats, whether it is a boy or a girl spider, and how the spider compares to the other spiders in the photographs. When the children ask their teachers what kind of spider it is, the teachers seem uncertain and wonder aloud how the class might figure it out. “We don’t jump at giving them the answers,” explains Jane Barber, classroom teacher. “Our intent is to focus on the processes of discovery, to teach them how to learn by not only observing but also using resources such as books and the Internet. We act as guides in the hunt for information.” In the weeks that follow numerous drawings of spiders are on display in the classroom, and the children count the legs and eyes, write their names on their drawings, and ask how to spell tarantula, spinnaret, and egg sac. The children want to write, because the writing is meaningful to them. The scientific inquiry, early literacy, and math opportunities naturally fall into place around the spider investigation.

Fostering creativity through investigations

Creativity seems to emerge from multiple experiences, coupled with a well-supported development of personal resources, including a sense of freedom to venture beyond the known.

—Loris Malaguzzi, The Hundred Languages of Children

Just off the center courtyard of our school there is a lovely building called the atelier, a French word, meaning workroom or artist’s studio. Historically, an atelier serves not only as a place where seamstresses, carpenters, painters, sculptors, and other artists could create their products, but also as a place that could offer inspiration and answers to their questions. Inspired by the schools of Reggio Emilia, we have created a special place, separate from the classrooms, where children use creative art as a tool to represent their ideas and feelings.

Though classrooms have a scheduled time each week to visit the atelier, teachers are welcome to bring small groups to the atelier to create at any time. The two teachers in our atelier have a close relationship with the classroom teachers. As colleagues, they communicate about the interests of the children and work going on in the classroom. Today, the children arrive in the atelier to find a shadow of a spider cast across the white tiled floor. They delight in this discovery and wonder how this can possibly be. Some reach down with hesitant hands to touch the dark shadow on the floor. Encouraged, they soon search out the source of the bright light. In the corner is an overhead projector with a spider photograph laying on the light tray. The teachers allow them to touch the equipment and investigate. They giggle at the discovery that the spider on the floor moves when the photograph moves. Some children ask if they can draw the spider. Anticipating this request, the teachers tear off a long sheet of butcher paper and the children sprawl out on the floor and begin to trace the shadow.

Although investigations often begin with children representing what they know through drawing, creating three-dimensional artwork is highly valued by teachers as a way to extend the learning. Clay, wire, wood, and recycled materials are used daily in the classrooms and the atelier to help children express what they know. As such, we ensure that the classrooms have many different kinds of materials that help the children piece it all together. Materials such as masking tape, packaging tape, wire, clay, and various kinds of glues and adhesives are available at easy access to the children. Again, we steer away from prepackaged materials. Instead we use open-ended, recycled materials, which are often donated by the parents. Children learn how to glue, cut, fold, tear, balance, and solve problems in the context of project work. Although the end product is deemed lovely, it is not the driver of the activity. Rather, it is the process of creating—the enjoyment of creating together—that is at the forefront of the endeavor.

An opportunity to move the children toward creating three-dimensional art becomes apparent during one of the class conversations. Ms. Woosley, the classroom teacher, explains, “It’s really surprising to us that it is the spider webbing the children are most interested in. One of the boys expressed concern that they were having trouble remembering where all of the webs were on the playground. We suggested creating a map of the playground, mapping where the spider webs were located. The children liked that idea.” A committee of students is formed to investigate how to make a map. Because the teachers are aware of another map project occurring on campus, they collaborate with colleagues in another classroom. The Spider Web Committee is invited to meet with the other classroom students to discuss strategies for mapping the playground.

In the weeks that follow, the two classrooms—using their individual drawings as guides—will create together one three-dimensional map of the playground. They label the spider web locations and create a map legend. Their knowledge of spider webs was extended to understanding maps, use of legends, and a compass, all within the context of group work.

Celebrating the child’s identity

Those of us who have been fortunate to teach for years in early childhood know well the elation we experience when our teaching goes well—when everything clicks into place. Our students share this same feeling when they experience success. This sense and level of satisfaction children experience creates an appetite for learning, a hunger to do it again—and again and again.

This is never more evident than the moment a child understands that he or she belongs, that he or she is a member of the group. In the first week of classes, teachers quickly cluster 8-inch by 10-inch photographs of the children on the walls surrounding the classroom circle space. Their names are printed boldly next to their images. As soon as possible, drawings and other forms of artwork appear next to each child’s photograph, with the child’s name written in his or her own hand, and a quotation about something the child likes.

But this is just the start of building the child’s identity. As you walk around the classroom space, you find family photographs donated by the parents and a basket of “All About Me” books that the parents have created using family photographs. These personal books are read over and over again as children seek comfort in sharing the names and faces of those most dear to them. There are individual mailboxes with their names and individual cubby spaces that belong only to them. It is an environment that opens its arms wide, surrounding children with a sense of who they are.

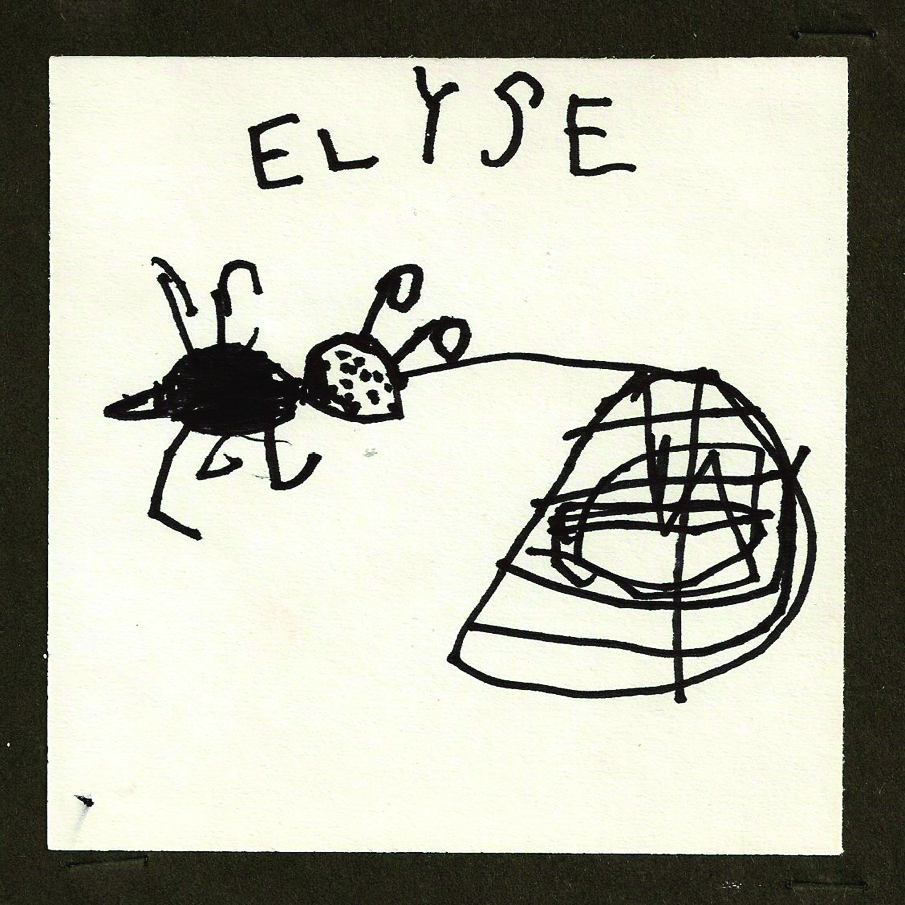

Project work and investigations easily lend themselves to fostering a child’s sense of identity. With the spider investigation, the teachers suggest that the children create a Bug Club. The Bug Club meets on the playground each day and sets out to find bugs and spider webs. “There were some children who were not engaged in the spider hunts occurring on the playground. However, when we created the Bug Club, everyone wanted to join in,” says Jane Barber, a classroom teacher. “We suggested that each child have a name badge to identify them as part of the club.” Using simple card stock, with yarn as a lanyard, the children draw a picture of their favorite bug and write their own first name. In addition, the children create their own Bug Club Journal. They use these journals to draw the creatures they find and to write down new words. The Bug Club Journals have the child’s name and photograph on the cover. To be a member of the Bug Club, you need your name badge, your journal, and a writing tool such as a marker, crayon, or pencil. As hoped, the children jumped at the chance to be a member of the club. “It just took off. We moved outside the playground, just beyond the gate, and the children were so excited. All they wanted to do was draw and draw. We were surprised and pleased at how they stayed on task, how careful they were with their drawings. Venturing out with the Bug Club became a part of our daily routine,” says Kristine Lundquist, classroom teacher.

As all teachers and parents know, there is a big difference between what a child is capable of doing and what a child is willing to do. You cannot teach someone who does not want to learn or someone who does not believe he or she can learn. If we want to promote the hunger for learning, then we should create environments in which students and teachers feel safe to venture beyond what is already known—environments that reflect our values and celebrate students and teachers as uniquely creative individuals.

Author’s Note: Transforming education happens only when we transform our teaching. My deep appreciation to Sabrina Ball, Jane Barber, Keri Woolsey, Kristine Lundquist, and the staff at Pinnacle for their leadership in creating playful and inquiry-based learning environments.

Mary Ann Biermeier, MEd, is director of professional development at Pinnacle Presbyterian Preschool. She devotes her time and passion to initiatives designed to resolve high rates of illiteracy in Arizona, helping teachers create learning environments that support all children.